The History of White People (28 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Fig. 14.2. Francis Amasa Walker as president of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ten years later, Lodge confidently presented supposedly hard proof of New Englanders’ superiority, in an article quoted approvingly for the next forty years. “The Distribution of Ability in the United States” (1891) quantified the conventional wisdom of the time in pages of tables and lists purporting to prove that Massachusetts had contributed the largest number of distinguished Americans: 2,686 of the 14,243 names in the six volumes of Appleton’s

Enyclopædia of American Biography

. Lodge’s methodology, with its subtle means of inclusion, worked fine for just about everybody in the race business, despite glaring weaknesses. For one thing, he gauged distinction according to the size of subjects’ portraits, so that a larger illustration in

Enyclopædia of American Biography

garnered two stars, while a smaller one got only one star, even after Lodge admitted that “portraits do not appear to have been distributed simply on the ground of ability and eminence.” For another, while forthrightly acknowledging the impossibility of figuring “race-extraction” with any confidence and tracing it only through the paternal line, he nonetheless continued to use racial categories based upon names and places of birth.

9

Never mind these limitations; Lodge still carried on to recognize the English as the greatest American “upbuilders.”

As for southerners, Lodge found them deficient, even though “no finer people ever existed than those who settled and built up our Southern States.” The problem was slavery, which “dwarfed ability and retarded terribly the advance of civilization.”

*

Southerners got shut out of regional greatness, but Lodge’s summary, in a crucial gesture of inclusion, reached beyond England to include “people who came from other parts of Great Britain and Ireland.”

10

New England still ruled, but the Irish now took their place within its glory.

A

S IN

the case of so many immigration restrictionists, Francis Amasa Walker’s New England descent seemed connected to his blood and virility. In 1923 Walker’s biographer called this father of six children the “fine flowering of all that was superior and, in the best sense, peculiar in New England before the Civil War.” Echoing a familiar theme of purity, the biography claims that Walker’s “ancestry was extraordinarily homogeneous. Almost all [his] forebears came over in the first great wave of English immigration before 1650, and there was afterwards little or no admixture from other than British stock.”

11

New England identity meant smart minds in handsome bodies, the sine qua non of Americanism. But would there be enough of them?

The census of 1880 had indicated a decline in the native white American birthrate. Since Walker firmly linked immigration to reproduction, he blamed native white Americans’ “decay of reproductive vigor…out of the loins…of our own people” on the pernicious influence of slovenly foreigners. True, he conceded, native white demographic stagnation did owe something to “luxurious habits,” “city life,” boardinghouse “habits unfavorable to increase of numbers,” and the Civil War’s toll on native white bodies. Succeeding racist and eugenicist thought would consistently echo the baleful effects of city life and war, both enemies of the health of “the race.”

*

But never mind, most trouble lay with the “monstrous total of five and a quarter millions” of recent foreign arrivals.

12

They posed the threat of racial endangerment.

Nativism and its cold-blooded, stock-breeding lexicon increased in volume, as during the 1890s Walker and others railed ever more stridently against the evils of immigration. “Degradation” joined “stock” as a leitmotif. In 1895 two articles entitled “The Restriction of Immigration” repeated “degradation” and “degraded” six times and “ignorant and brutalized peasantry” twice. “Loins” appeared often, too, euphemistically attached to both Anglo-Saxon and immigrant, as in the loins of “beaten men from beaten races; representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence.” Phrases destined for greatness.

L

IKE

S

AM

H

OUSTON

, Walker contrasted

old

and

new

immigrants, but his chronology betrayed slipperiness between good (“old” pre–Civil War German and Irish) and bad (“new” immigrants arriving later on). Yes, the immigration problem had first appeared in the 1850s with the “degraded peasantry” needed to build the railroads and canals. Look, he warned, how the influx had reduced native whites’ fertility. Clearly native-born Americans had begun to “shrink” from competition with early Irish. Now it was happening all over again, only somehow the “old” Irish immigrants were becoming Americans and, inexorably, failing demographically, too.

*

Without much explanation, Walker admitted the Irish immigrants into the American fold as northern Europeans. With Americanization came demographic failure, so that the Irish as Americans were, in their turn, “shrinking” from competition with Italians and no longer reproducing mightily. But this time the Americanization process had come to a halt. Walker thought the new immigrants, unlike the old ones, had to remain inherently repulsive.

13

In no way could these new hordes evolve like northern Europeans; they would inevitably “degrade” American citizenship.

For Walker, cheap, easy transatlantic transportation was partly to blame for lowering the caliber of immigrants. In the old days, only the brave and enterprising ventured across the seas. But now “Hungarians, Bohemians, Poles, south Italians, and Russian Jews,” from “every foul and stagnant pool of population of Europe,” could reach the United States with ease. These “vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions,” lacked all “the inherited instincts and tendencies” of native (white) Americans. Walker did not hold back: “Their [the new immigrants’] habits of life, again, are of the most revolting kind.”

Moreover, and most significantly for Walker, these “masses of alien population” created problems spanning politics, the economy, and demography: laboring for low wages, they offered a harvest of ignorant workers ripe for demagogues. Lured into labor unions, they could easily be “duped” into going on strike. Such immigrant radicalism threatened the very health of American democracy.

The themes trumpeted by Walker and seconded by Lodge—New England superiority, reproductive competition, and labor radicalism—expressed a deeply conservative ideology that perverted Darwinian natural selection and feared worker autonomy. These notions would enjoy great longevity in the new language of truth: racial science. Supposedly rigorous and attentive to natural laws, racial science supplied the theory and praxis of difference among Europeans (as well as the descendants of Africans) in the United States. No longer stigmatized as inherently different, Irish and Germans entered a second enlargement of American whiteness to become constituent parts of

the

American. For now there were newcomers to toil at hard labor and be stigmatized as racially inferior.

THE RACES OF EUROPE

F

rancis Amasa Walker’s famous cliché “beaten men from beaten races” played well in white race science, but Walker was hardly out there alone crying in the wilderness. Scores of others—men like the author and lecturer John Fiske and scholars from high academia, like the era’s leading sociologist, Edward A. Ross, and the pioneering political scientist Francis Giddings of Columbia—joined Walker in pushing northern European racial superiority over new immigrant masses. At the other end of the spectrum, the American Federation of Labor also drew the line against the new immigrants as “beaten men of beaten races.”

1

But Walker, who was to die in 1897, stood highest in influence, practically dictating how Americans would rank white peoples for decades, a period that introduced William Z. Ripley.

Originally from Medford, Massachusetts, William Z. Ripley (1867–1941), like Walker and Lodge, advertised his New England ancestry: his middle name, Zebina, he said, honored five generations of Plymouth ancestors.

*

Ripley contrasted “our original Anglo-Saxon ancestry in America” with that of “the motley throngs now pouring in upon us,” and, like Walker, he attended to his manly and nattily dressed appearance.

2

(See figure 15.1, William Z. Ripley.) With Ripley it was smart minds in handsome bodies all over again—and, one might add, education and connections.

After gaining a bachelor’s degree in engineering from MIT, Ripley took a Ph.D. in economics at Columbia, writing a dissertation on the economy of colonial Virginia. After two years’ lecturing at MIT and Columbia, Ripley found himself at somewhat loose ends in 1895. He needed a better-paying job, and an aging Francis Walker needed a scientific classification of American immigrants. Walker chose Ripley, his favorite student, and Ripley seized this opportunity to codify the gaggle of immigrants.

3

*

Ripley later said that

The Races of Europe

took nineteen months of work. To a scholar these days that seems not very long. Working with his suffragist wife, Ida S. Davis, and librarians at the Boston Public Library, Ripley synthesized the writings of hundreds of anthropologists.

4

†

John Beddoe in England and Joseph Deniker and Georges Vacher de Lapouge in France proved especially helpful. European anthropologists had been compulsively measuring their populations for decades, offering Ripley tens of thousands of detailed measurements, charts, maps, and photographs. Ripley used them all. Such exhaustive scholarship, together with the “Ph.D.” attached to Ripley’s Anglo-Saxon name on the title page, endowed

The Races of Europe

with a glowing scientific aura.

Ripley’s work first reached the public as a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1896. Earlier in the century the Lowell Institute had offered its podium to likely speakers on race such as George Gliddon (Josiah Nott’s collaborator) and Louis Agassiz (soon to join the Harvard faculty). The New York publisher Appleton issued the lectures serially in

Popular Science Monthly

and then published a generously illustrated book in 1899.

*

Fig. 15.1. William Z. Ripley, professor of economics, Harvard University, ca. 1920.

Weighing in at 624 pages of text, 222 portraits, 86 maps, tables, and graphs, and a bibliographical supplement of more than two thousand sources in several languages, the sheer heft of

The Races of Europe

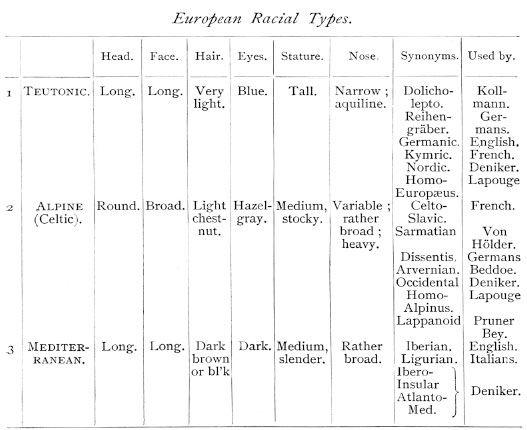

intimidated and entranced readers, blinding most of them to its incoherence. Ripley himself may have been blinded by the magnitude of his task, aiming as he did to reconcile a welter of conflicting racial classifications that could not be reconciled. (See figure 15.2, Ripley’s “European Racial Types.”) In this table Ripley presents “traits” he considered important—head shape, pigmentation, and height—along with the multiple taxonomies posited by various scholars.

One glaring taxonomic dilemma appears in the inclusion of “Celtic,” in parentheses, beneath “Alpine.” Anthropologists had long struggled to sort out the relationship between ancient and modern Celts, between the Celtic regions of Europe such as Ireland and Brittany, and between ancient and modern Celtic languages such as Gaelic. Was France a Celtic nation? Yes and no. French Republicans embraced their nation’s revolutionary heritage, identifying with such glorious ancient Celtic heroes as Vercingetorix, the tragic protagonist of Caesar’s

Gallic War

.

5

Royalists like Alexis de Tocqueville and his companion Gustave de Beaumont, in contrast, proudly claimed descent from Germanic conquerors. Beaumont, we remember, gave his French protagonist in

Marie

the Frankish name Ludovic rather than the more familiar French Louis.

Ripley’s parenthesis does not solve the Celtic problem, and he stoops to insert Georges Vacher de Lapouge (a cranky, reactionary librarian at a provincial French university whom we will encounter again later) into the list of authorities. Ripley thereby conferred a measure of scientific recognition, although Lapouge’s fanatic Aryan/Teutonic chauvinism destroyed his standing in France. Questionable scholarship aside, Ripley had set out to transcend “the current mouthings” of the racist lunatic fringe, and his thoroughness inspired confidence for years. Ordinary readers judged his book scientific, and anthropologists hailed his methodology.

Fig. 15.2. “European Racial Types,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

N

OTHING EVER

got truly settled in race science, but Ripley came close. How many European races were there? Ripley says three: Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean. What criteria to use? Following accepted anthropological science, Ripley chooses the cephalic index (the shape of the head; breadth divided by length times 100), “one of the best available tests of race known.”

6

Add to that information about height and pigmentation, and he has nailed each of the three white races:

Teutonics: tall, dolichocephalic (i.e., long-headed), and blond;

Alpines: medium in stature, brachycephalic (i.e., round-headed), with medium-colored hair;

Mediterraneans: short, dolichocephalic (i.e., long-headed), and dark.

The cephalic index was not new. In fact, a real European scholar, the Swedish anthropologist Anders Retzius, had invented it in 1842, coining the terms “brachycephalic” to describe broad heads and “dolichocephalic” to describe long heads. The technique quickly took hold in Europe, where researchers took to measuring heads by the tens of thousands.

Anthropologists loved the cephalic index because it seemed to measure something stable, and race theorists demanded permanence. Heads supposedly remained constant across an endless succession of generations. Concentration on the head was not new. A skull, we recall, had inspired Blumenbach’s naming white people “Caucasian.” Samuel George Morton and Josiah Nott had backed up their assertions of white supremacy with Mrs. Gliddon’s drawings of skulls. France’s Paul Broca, his generation’s most renowned anthropologist, also based his race theories on skull measurements.

Retzius and other fans of the cephalic index had no trouble linking head shape with “racial” qualities such as enterprise, beauty, and, of course, intelligence. Theorizing from old skulls, they envisioned primitive, ancient, Stone Age Europeans—often identified as Celts—as brachycephalic and also dark in color. Accepted theory soon held that long-headed dolichocephalics had invaded Europe and conquered these primitive, broad-headed people. A lot of the old natives were still around, people considered backward, such as the brachycephalic Basques, Finns, Lapps, and quite a few Celts; they were still assumed to be primitive natives, like peasants and other supposedly inert groups.

*

Following the English anthropologist John Beddoe, Ripley gingerly notes “the profound contrast which exists between the temperament of the Celtic-speaking and the Teutonic strains in these [British] islands…. The Irish and Welsh are as different from the stolid Englishman as indeed the Italian differs from the Swede.”

7

This idea of temperament as a racial trait was based on a perversion of Darwinian evolution. With a perfectly straight face anthropologists reasoned that evolution operated on entire races (not individuals or breeding populations), that races had personalities, and that physical measurements of heads betokened racial personality.

Over time the cephalic index both dominated as a symbol of race and became a two-edged sword when color was added to it. Long-headed people, “dolichocephalics,” for instance, should be light and Teutonic (good) or dark and Mediterranean (bad). Alpines (maybe middling, maybe bad) were supposed to be brownish and brachycephalic. These correlations counted as “harmonic” correspondence. Rather than deal with people who did not fit the pattern, such as blond Alpines, race-minded anthropologists them deemed “disharmonic” and then just ignored them. Perfectly “harmonic” Mediterraneans with long heads and dark hair, eyes, and skin also faded from view, because anthropologists judged them to be obviously inferior and therefore of scant interest.

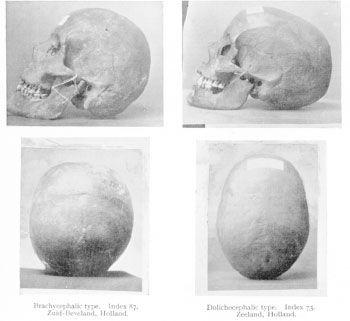

At first all this measuring of heads meant little to most Americans. Slavery and segregation had seen to it that race resided most obviously in skin color, or at least in physical appearance or ancestry that could be classified as black or white. But up-to-date experts stuck to their guns, proffering scientific explanation via visuals. (See figure 15.3, Ripley’s brachycephalic and dolichocephalic skulls.) A caption at the lower left reads, “Brachycephalic type. Index 87. Zuid-Beveland, Holland,” and refers to photographs on the left. On the lower right, “Dolichocephalic type. Index 73. Zeeland, Holland” refers to photographs on the right.

*

These images were intended to show the difference between a long, dolichocephalic skull with a cephalic index of 73 and a round, brachycephalic skull with a cephalic index of 87.

Fig. 15.3. Brachycephalic and dolichocephalic skulls, in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

Since ordinary readers rarely encountered skulls in everyday life, and Ripley badly wanted them to understand, he added photographs of racial “types” along with their cephalic indices for further clarification. (See figure 15.4, Ripley’s “Three European Racial Types.”)