The History of White People (27 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

But Nott had resolved to spread the word to American audiences. In 1855 he hired the twenty-one-year-old, Swiss-born Henry Hotze of Mobile to help him translate Gobineau’s

Essai

, but strictly according to Nott’s southern slaveholding ideology.

12

*

This translation, entitled

The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races: With Particular Reference to Their Respective Influence in the Civil and Political History of Mankind, from the French of Count A. de Gobineau

(1856), bears Gobineau’s name as author, but much of it is pure Nott. For instance, he corrects Gobineau’s lack of interest in African slavery through a polygenesist appendix of his own, showing Morton’s cranial measurements laid out according to Morton’s taxonomy. Gobineau, interestingly, denounced this amendment as a distortion of his thought.

The denunciation was well deserved, for Gobineau says quite clearly that Africans contribute positively to the mixture of races in prosperous metropolitan centers by offering Dionysian gifts such as passion, dance, music, rhythm, lightheartedness, and sensuality. Whites, for their part, contribute energy, action, perseverance, rationality, and technical aptitude: the Apollonian gifts. In the short run, and even though the final outcome must entail utter ruin, this is all for the good, at least for Gobineau. But not for Nott. While Gobineau sees whites as obviously racially superior, they are insufficient in and of themselves and need the contributions of other races for the development of civilization.

13

†

Gobineau’s Africans contribute to mixture, even though mixture inevitably causes revolution. The European revolutions of 1848 terrified Gobineau, but failed to interest Nott.

Other sharp differences divided Nott and Gobineau. They lived on different continents, surrounded by different peoples, and motivated by different political events. Each defined the concept of “races” in order to answer his particular needs. Gobineau was an antidemocratic reactionary explaining political revolution by pitting the Aryan race against other, inferior, white-skinned races; Nott, a slaveholding reactionary railing against abolitionists, saw a white race pitted against a black one. Race as color occupied Nott’s center stage, while Gobineau kept his eye on Celts, Slavs, and Aryans. As a result, Nott’s loose translation retained Gobineau’s fear of race mixing but discarded whatever else did not apply: out went Gobineau’s anxieties over the people of eastern Europe and his pessimistic view of white Americans.

14

*

All in all, Nott’s awkward translation of Gobineau never added much to America’s racial bubbling, never amounted to much more than an obscure provincial publication.

15

†

E

ARLY ON

, in 1843, Nott had published an important article on miscegenation, racial science’s bugaboo. His title says it all: “The Mulatto a Hybrid—probably extermination of the two races if the Whites and Blacks are allowed to marry.”

16

Why would Nott write that the mating of blacks and whites would produce infertile hybrids, when a glance around his own Alabama neighborhood would have put the lie to this notion? More to the real point, the possibility of mixed marriage doubtless annoyed Nott far more than the inevitable mixed sex. In any case, while this theory of infertile progeny made no sense in theory or practice, it did serve Nott’s scholarly purposes and pushed along his fine scientific reputation.

Having made his name, Nott burnished it by compiling two anthologies:

Types of Mankind

(1854) and

Indigenous Races of the Earth

(1857), both published with George R. Gliddon, an Englishman long resident in Egypt who had supplied Morton with skulls and Nott with inspiration. Gliddon’s wife drew the illustrations in

Types of Mankind

.

17

That both of these flimsy books sold extremely well demonstrates how little rigor nineteenth-century scholarly race talk required. Cobbled together from miscellaneous pieces in various genres and lengths by a wide array of contributors, each anthology included pieces by Louis Agassiz, whose luminous European origin and Harvard affiliation gave any work a certain scientific cachet.

L

OUIS

A

GASSIZ

(1807–73), a charming, German-educated Swiss physician-scholar, had made his name as a follower of the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. Glimpsing opportunity across the sea, Agassiz sailed to the United States in 1846 on the kind of lecture tour intended to generate permanent, remunerative employ.

*

Stopping first in Philadelphia, Agassiz paid his respects to Samuel George Morton, then moved on to deliver lectures in 1847 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he found sponsors of a professorship at Harvard.

Twelve years later, Charles Darwin published

On the Origin of Species

, a book that conquered biology and changed science forever. But Darwin did not conquer Agassiz, who, famously, never accepted Darwin’s concept of evolutionary change. To his very end, Agassiz preferred a polygenesist scheme in which God had created the races separately at the very beginning. Even so, with the founding of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, Agassiz presided over a scholarly institution of enormous influence. For twenty-six years, until his death, he shaped not only the world of American natural history museums but also the field of American anthropology, which natural history museums housed until well into the twentieth century. This legacy he passed on to his Harvard protégé and successor, the Kentuckian Nathaniel Southgate Shaler (1841–1906).

Shaler became a fixture at Harvard during the 1870s, often referring to Agassiz as “my master.” As a professor of geology, paleontology, and scientific truth in general, Shaler taught a generation of men destined to lead the United States, including Theodore Roosevelt. Through his commentary on American life, Shaler’s Anglo-Saxon chauvinism provided a bulwark to the New England–based movement against immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Today, after the mid-twentieth-century reshuffling of race into a black/white binary, Shaler appears in history as a proponent of black inferiority. But in the 1880s and 1890s, he also—and mainly—helped elevate the figure of the white male Kentuckian into an emblem of America and took aim at southern and eastern European immigrants as menaces to American racial integrity.

T

HE

A

MERICAN

school of anthropology faded after the publication of its masterworks in the 1850s.

18

One of its core tenets—that different races constitute different species and stemmed from several separate racial creations (polygenesis)—lost a good deal of credibility with the publication of Darwin’s

Origin of Species

in 1859. But its racist notions served the needs of American culture too well to disappear entirely. Indeed, the American school’s founding belief in permanent and unchanging racial identity has yet to expire.

By the early 1890s, the American leaders in anthropology—Morton, Nott, Agassiz—had done their work and passed from the scene. White race taxonomy was, in any case, evolving into notions of immigration restriction and eugenics. Samuel George Morton had died at fifty-two in 1851; following Confederate service and disappointment with the post-slavery South, Nott died in 1873, the same year as Louis Agassiz. After a long cognitive decline, Agassiz’s friend Emerson died in 1882, as did Gobineau.

They left behind a dour legacy: the fetishization of tall, pale, blond, beautiful Anglo-Saxons; a fascination with skulls and head measurements; the drawing of racial lines and the fixing of racial types; the ranking of races along a single “evolutionary” line of development; and a preoccupation with sex, reproduction, and sexual attractiveness. All this proved not only durable but also applicable to people now considered white.

T

empting though it may be to cling to a simple history of whiteness stretching back through American history, our task here is to reveal the historical record, where we find a far more complex story. Rather than a single, enduring definition of whiteness, we find multiple enlargements occurring against a backdrop of the black/white dichotomy.

Any nation founded by slaveholders finds justification for its class system, and American slavery made the inherent inferiority of black people a foundational belief, which nineteenth-century Americans rarely disputed. Very few believed that people of African descent belonged within the figure of

the

American. At the same time, Americans rarely excluded Europeans from the classification of “white,” especially when it came to politics and voting. After property qualifications for voting ended in the first half of the nineteenth century—the first enlargement of American whiteness—virtually all male Europeans and their free male children could be naturalized and vote as white. Thus, matters of legal American race remained relatively clear as a question of black/white, especially in the South. “Southerner” meant white southerner; “American” required whiteness, but mere whiteness might not suffice in society. Although determining who counted as “white” for political purposes was clear, whiteness in and of itself got one only so far toward being part of

the

American.

As we have seen, enormous efforts went into enthroning the Teutonic/Saxon/Anglo-Saxons, tracing them back to a tough Germanic-Scandinavian strain, conquerors of old, never themselves conquered. This heroic depiction left out a gaggle of Celts: those millions of French, Irish, and northern Scots and their children who were assumed to lack Saxon blood. In the mid-nineteenth century, it was mostly Irish Catholics who raised the issue. For Ralph Waldo Emerson, they were not deeply, truly Americans. Nor were certain Catholic and Jewish Germans. In this sense, Emerson’s time was passing.

T

HE

C

IVIL

War offered a huge opening. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants volunteered for military service on both sides. Not surprisingly, the Union Army, about one-fourth of whose personnel came from abroad, benefited from immigrant support more than the Confederacy. Some immigrants were well integrated into heterogeneous Union forces as Irish and Germans scattered throughout a panoply of regiments. In addition, and quite shrewdly, the Union Army organized itself along national lines. Among its thirty-six Irish units were the New York Fighting Sixty-ninth, the Irish Zouaves, the Irish Volunteers, and the St. Patrick Brigade. Italians made up the Garibaldi Guards and the Italian Legion. The eighty-four German units included the Steuben Volunteers, the German Rifles, and the Turner Rifles.

1

Confederates looked askance at the Union’s polyglot ranks, and for decades afterwards Civil War Decoration Day holidays offered embittered former Confederates occasions to characterize their side as “American” and to impugn the Union Army as “made up largely of foreigners and blacks fighting for pay.”

2

Conversely, former Unionists—and most Democrats—saw immigrants’ service as a multicultural victory over Know-Nothing nativism. According to one minister, the children of the dead, thanks to the sacrifice of their immigrant fathers, are “no longer strangers and foreigners, but are, by this baptism of blood…consecrated citizens of America forever.”

3

Union Decoration Day oratory projected the sunny side of wartime immigrant Americanization, helping to usher hundreds of thousands into the white American club. Such a view, however, was far from universal. The Republican Party and its media spokesmen initially saw such easy Irish Americanization as little more than another facet of traditional, Democratic, proslavery white supremacy.

The extremely popular and influential

Harper’s Weekly

and its brilliant German cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840–1902) led the charge. Siding with southern black Republicans against northern Irish Democrats, Nast appropriated a caricature long popular in England week after week. He depicted Irishmen as brutal, drunken apes—rioting on St. Patrick’s Day, overturning Reconstruction in the South, and cynically crashing their way into American politics as white men. By allying with former Confederates and fat-cat northern Democrats, Irishmen were said to be trampling the rights of loyal black southern defenders of the Union. To Nast, Irish opportunity meant the black man’s defeat. Of course, both opportunity and defeat had taught the Irish how politics worked in America. Race, in black and white terms, retained its importance. (But race did not matter above all. No women could vote.)

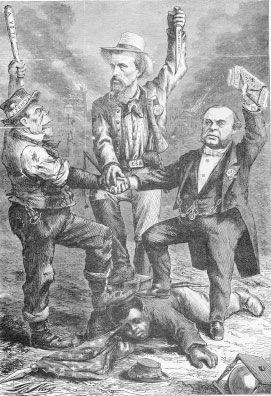

Consider Nast’s 1868 cartoon. (See figure 14.1, “This Is a White Man’s Government.”) A stereotypical Irishman on the left swears allegiance to the Confederate (CSA on his belt buckle) in the middle, with Horatio Seymour, a New York Democrat plutocrat, holding graft money, on the right.

*

The Irishman’s shillelagh reads “a vote,” referring to a tendency of Irish immigrants to vote the Democratic ticket and, presumably, thereby to undermine true American values. The Irishman’s hat saying “5 points” recalls the bloody Saint Patrick’s Day riot of 1867 in New York City’s biggest slum.

†

Behind the Irishman, a building in flames, the “Colored Orphan Asylum,” refers to its destruction by an Irish mob during the deadly 1863 draft riots. Together, these three figures trample the loyal black American veteran, whose Union soldier’s hat and American flag lie in the dust, the ballot box beyond his reach. Nast’s only half-ironic caption reads, “This Is a White Man’s Government.”

Fig. 14.1. Thomas Nast, “This Is a White Man’s Government,”

Harper’s Weekly,

1868.

Without a doubt, Nast’s cartoon reflects a good deal of reality. Irish workers had shown little hesitation in brandishing their new-found whiteness as a tool against others. In the West of the 1880s, Irish workingmen agitated as “white men” to drive Chinese workers off their jobs and out of their homes. This anti-Chinese movement produced the country’s first race-based immigration legislation, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Although not all Chinese immigrants fell under the law—merchants, teachers, students, diplomats, and other professionals were exempted—the Irish and other whites continued to attack the Chinese in a series of western pogroms called the “Driving Out.”

4

As it would again, “racial” violence addressed economic competition.

In the 1870s and 1880s, politics began to serve the economic interests of Irish and German immigrants in many walks of American life. The right to vote, for instance, opened a path to employment through government patronage and civil service jobs. Labor union control meant that their sons and brothers stood first in line for steady work and, later, skilled jobs. The figure of the Irish policeman owes its longevity to this system of public employment. Thanks to patronage jobs and government contracts, fewer in the second and third generations suffered the grinding poverty that had dogged their famine immigrant ancestors. Along the way they learned, in true American fashion of the time, to profit from the vulnerability of nonwhite Americans barred from voting—hence barred from the fruits of bloc voting.

5

Color mattered, even for Ralph Waldo Emerson, that preeminent Saxonist.

E

MERSON HAD

his contradictions, of course. In

English Traits

of 1856, he both denounced and embraced racial determination. In

Conduct of Life

of 1860, he again both deprecated and then echoed the racist views of Robert Knox, describing the “German and Irish millions, like the Negro,” as races with “a great deal of guano in their destiny.”

6

Ever a Saxon chauvinist, Emerson could nonetheless soften toward poor immigrants, presumably Irish, provided their bodies were sufficiently light in color. In 1851 Emerson cast his eye on the newcomers around him, judging them, in most cases, as suitable to join his world.

America. Emigration.

In the distinctions of the genius of the American race it is to be considered, that, it is not indiscriminate masses of Europe, that are

transportedshipped hitherward, but the Atlantic is a sieve through which only or chiefly the liberal adventurous sensitive

America-loving

part of each city, clan, family, are brought. It is the light complexion, the blue eyes of Europe that come: the black eyes, the black drop, the Europe of Europe is left.

7

For Emerson, as for his admirers, it was the blue eyes and the light complexion that conferred on the Irish a real-American identity. With the arrival of millions of dark-eyed new immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century, his preferences counted ever more heavily.

As many immigrants poured into the United States, a new hierarchy was under construction, one placing Anglo-Saxons at the top and the Irish just below, soon to be incorporated into the upper stratum of northwestern Europeans as “Nordics.” The newest newcomers, Slavic immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian empire, Jews from Russia and Poland, and Italians, especially those from south of Rome, had still to be judged and rated. This sorting out took place within a history of older waves of immigration.

Back in the mid-nineteenth century, masses of impoverished Catholics had inspired contrasts between “old” and “new” immigrants. The Texas founding father Sam Houston had contrasted the old immigration of the colonial generation, on the one hand, and the new, midcentury Catholics, on the other. Now, at the turn of the twentieth century, Catholic Irish and Germans were assuming their place as “old” immigrants, while the “new” immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were being slotted where Houston’s famine Irish had been. In their penury and apparent strangeness, the new immigrants after 1880 made Irish and Germans immigrants and, especially, their more prosperous, better-educated descendants seem acceptably American.

Thus occurred the second great enlargement of American whiteness. It came with such reluctance and with so many qualifications and insults that Irish Americans continued to feel excluded and aggrieved. It took a very long time for the realization of acceptance to sink in, for it had begun in the middle of the nineteenth century and stretched across the lifetimes of a generation and more. The commentary was far more likely to castigate new immigrants than to welcome the old. In the great hue and cry over this new round of immigration, the voice of one New Englander carried farthest.

I

N THE

1890s, Francis Amasa Walker (1840–97), the most admired American economist and statistician of his time, laid the scientific groundwork by publishing a number of influential articles positing the need to limit the number of immigrants. (See figure 14.2, Francis Amasa Walker.) The son of a professor of economics who also served in the U.S. Congress, Walker graduated from Amherst College in 1860 and rose through Union Army ranks during the Civil War. After studies in Germany, he was appointed director of the U.S. census of 1870. He directed the census of 1880 while attached to the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University between 1872 and 1880. In 1881 he became president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in the following years presided over both the American Statistical Association and the American Economic Association (AEA). Until the creation of the Nobel Prize in economics in 1969, the AEA’s annual Walker Prize stood as the world’s highest honor accorded an economist. Having been born in Boston, moreover, Walker was almost automatically deemed smart, able, and enterprising. Who better than a Bostonian to tell Americans what they needed to know? And Walker had some help.

The idea of

New England

, as we have seen, played a pivotal role in American race thought. Ostensibly a regional identity, New England stood for racial Englishness—vide

English Traits

. In this sense, the writing of American history bristled with race talk, as the Brahmin author and congressman Henry Cabot Lodge showed in his well-regarded books.

Lodge was an expert on Anglo-Saxon law, the topic of his Harvard Ph.D. dissertation. By 1881 he had taught at Harvard for three years and was starting his political career, sped along through a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute (where we have already seen Louis Agassiz) and publication of his 560-page

Short History of the English Colonies in America

. A perfect specimen of Anglo chauvinism, this book ascribes the greatness of the United States to the “sound English stock” of the middle classes and the “fine English stock” of families like George Washington’s, “good specimens of the nationality to which they belonged, and…a fine, sturdy, manly race.”

8

Again and again, Lodge trumpets the qualities of “the English race” and bases the inevitability of American independence on the intrinsic worthiness of that race.