The History of White People (12 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Fig. 6.3. “Mongol Types,” Kalmucks, in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

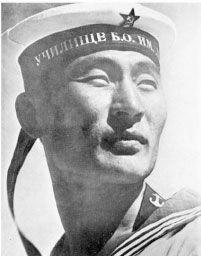

Fig. 6.4. “A Kalmyk Sailor,” in Corliss Lamont,

The Peoples of the Soviet Union

(1946).

A

LL OF

this classification appears in Blumenbach’s first edition.

Revising

On the Natural Variety of Mankind

in 1781, he adds the newly discovered Malays, thereby introducing a fivefold categorization. Note, however, that Europeans are not yet labeled Caucasian. Blumenbach explains that five groups, termed “varieties,” are “more consonant to nature” than the four Linnaeus had enumerated and that Blumenbach had originally accepted.

*

In 1781 Blumenbach also returns to the problem of the Lapps, finally admitting them as Europeans of Finnish origin, “white in colour, and if compared with the rest, beautiful in form.”

10

As Europeans continued to discover ever more human communities, increasing numbers of peoples and their geographical boundaries aggravated the chaos of classification. Blumenbach revised once again.

In his third edition, published on 11 April 1795, Blumenbach does not increase the number of human varieties. But he gamely notes the existence of twelve competing schemes of human taxonomy and invites the reader to “choose which of them he likes best.” Three experts, including his Göttingen colleague Christoph Meiners, designate two varieties (Meiners’s were “handsome” and “ugly”); one posits three; six designate four; one, Buffon, speaks of six varieties (Lapp or polar, Tatar, South Asian, European, Ethiopian, and American); and one designates seven.

11

Such anarchy had dogged human taxonomy from the beginning, for scholars could never agree on how many varieties of people existed, where the boundaries between them lay, and which physical traits counted in separating them. Nor have two hundred and more years of racial inquiry diminished confusion on this issue. Blumenbach’s idea of five varieties gained acceptance, but it was his introduction of aesthetic judgments into classification in 1795 that gave us the term “Caucasian.”

12

B

Y

1795, twenty years had passed since the first publication of

On the Natural Variety of Mankind.

In the interim, skin color, not heretofore the crucial factor for Blumenbach, had risen to play a large role. He now sees it necessary to rank skin color hierarchically, beginning, not surprisingly, with white. Believing it to be the oldest variety of man, he puts it in “the first place.” His reckoning includes a large dose of aesthetic reasoning, led by the blush.

*

“1. The white colour holds the first place, such as is that of most European peoples. The redness of the cheeks in this variety is almost peculiar to it: at all events it is but seldom to be seen in the rest.” After white comes “

the yellow, olive-tinge

.” Then, third, “

copper colour

(Fr.

bronzé

)” fourth is “

Tawny

(Fr.

basané

)” last, “the

tawny-black

, up to almost a pitchy blackness (

jet-black

).”

13

Like the first and second editions, this third edition of

On the Natural Variety of Mankind

keeps on ascribing differences of skin color to climate and individual experience in non-Europeans as well as Europeans.

Blumenbach seems once again to be arguing with himself, disregarding his own equitable explanation of individual difference and yet describing

the

“racial face” of each of his five human varieties. He dwells longest and lovingly on the Caucasian, from whom Lapps, having in 1781 been allowed a place, are once again excluded:

Caucasian variety

. Colour white, cheeks rosy; hair brown or chestnut-colored; head subglobular; face oval, straight, its parts moderately defined, forehead smooth, nose narrow, slightly hooked, mouth small. The primary teeth placed perpendicularly to each jaw; the lips (especially the lower one) moderately open, the chin full and rounded. In general, that kind of appearance which according to our opinion of symmetry, we consider most handsome and becoming. To this first variety belong the inhabitants of Europe (except the Lapps and the remaining descendants of the Finns) and those of Eastern Asia, as far as the river Obi, the Caspian Sea and the Ganges; and lastly, those of Northern Africa.

14

Like many other anthropologists, Blumenbach labels North Africans “Caucasian.” No problem there, at least not for the moment. But by placing the Caucasian variety’s eastern boundaries farther to the east than the Ural Mountains and as far south as the Ganges, Blumenbach enlarges Caucasian territory beyond the limits then becoming accepted as European.

*

Russia, always a problem, was sometimes placed within, sometimes outside Europe.

By bringing India into the Caucasian fold, Blumenbach was doubtless thinking linguistically. In 1786, the linguist Sir William Jones had traced similarities in various European and Asian languages to the archaic language of Sanskrit. Blumenbach’s colleague and friend Georg Forster had translated Jones’s version of an ancient Sanskrit classic drama into German in 1791. Others soon transformed a linguistic category, the Indo-European, or Aryan, into a race, giving rise to the idea of a biologically determined Indo-European people. By the mid-nineteenth century, scrupulous scholars had rejected any biological basis to the Indo-European/Aryan language group, but that hardly mattered. The judgment of sound scholarship did not suffice to kill off the notion of an Indo-European/Aryan race, with Germans and Greeks within and Semites outside. For determined racists, especially in the twentieth century, racial identity and language always had to coincide, and appearance would always figure in concepts of race. Race begat beauty, and even scientists succumbed to desire.

W

ITH THE

concept of human beauty as a scientifically certified racial trait, we come to a crucial turning point in the history of white people. Now linking “Caucasian” firmly to beauty, Blumenbach remained divided of mind. Holding first place in his classification was always the scientific measurement of skulls. But second within human variety came a concern for physical beauty, going well beyond the beauty of skulls and giving birth to a powerful word in race thinking: “

Caucasian variety

. I have taken the name of this variety from Mount Caucasus, both because its neighborhood, and especially its southern slope, produces the most beautiful race of men, I mean the Georgian.” A long footnote follows, quoting the seventeenth-century traveler Jean Chardin as only one of a “cloud of eye-witnesses” praising the beauty of Georgian women. Blumenbach’s quote leaves out Chardin’s disapproval of Georgians’ heavy use of makeup, their sensuality, and the many bad habits Chardin had deplored. Now Chardin intones to Blumenbach the gospel of Georgian beauty:

The blood of Georgia is the best of the East, and perhaps in the world. I have not observed a single ugly face in that country, in either sex; but I have seen angelical ones. Nature has there lavished upon the women beauties which are not to be seen elsewhere. I consider it to be impossible to look at them without loving them. It would be impossible to point to more charming visages, or better figures, than those of the Georgians.

15

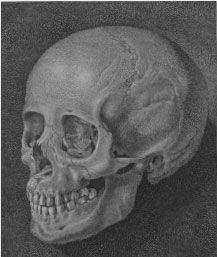

Beauty’s charms reached into science, but what of science’s bedrock, the measurement of skulls?

Now Blumenbach squirms. By turns he embraces Enlightenment science—the measurements of his skulls—then lets go to reach for romanticism’s subjective passion for beauty. Yes, skull measurements count, but when it comes down to it, bodily beauty counts for more, but no, no, not conclusively. Even while extolling Caucasian beauty, he adopts a third line of reasoning meant to puncture European racial chauvinism. Consider the toads, says Blumenbach: “If a toad could speak and were asked which was the loveliest creature upon god’s earth, it would say simpering, that modesty forbad it to give a real opinion on that point.”

16

As in the first edition of

On the Natural Variety of Mankind

, Blumenbach qualifies his estimation of European beauty as rife with European narcissism.

Even so, he uses the word “beautiful” five times on one page in describing the bony foundation of his favorite typology, a Georgian woman’s skull. It is “my beautiful typical head of a young Georgian female [which] always of itself attracts every eye, however little observant.

*

(See figure 6.5, Blumenbach’s “Beautiful Skull.”)

T

HE STORY

of Blumenbach’s skull belongs within a long and sorry history of Caucasian vulnerability to eighteenth-century Russian imperialism. Blumenbach’s benefactor Georg Thomas (Egor Fedotvich), Baron von Asch (1729–1807), is little known today. Born in St. Petersburg of German parents, Asch had secured his medical degree from the University of Göttingen in 1750 and then joined the Russian army’s medical service in the imperial forces of Catherine the Great. A military man and a leader of Russia’s learned societies in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Asch traveled around the expanding Russian empire both in his official capacity and as a patron of science. Regarding the latter, he collected skulls, manuscripts, and various other trophies from throughout Russia and its hinterlands in the 1780s and 1790s, specimens he showered on Blumenbach and the research collections of his Göttingen alma mater.

*

Fig. 6.5. Blumenbach’s “Beautiful Skull of a Female Georgian.”

In 1793, shortly after Catherine had won her second Caucasian war against the Ottomans, Asch sent Blumenbach a pristine female skull, explaining its provenance in a cover letter.

17

The skull came from a Georgian woman the Russian forces had taken captive, precisely the kind of situation figuring in so many descriptions of beautiful Caucasian and Circassian women: as an archetype, she is a pitiful captive lovely in her subjection. Actually, the perfect appearance of the teeth support a suspicion that the owner was a very young person, indeed, more adolescent than woman. In this case, the story continued to its tragic end when the woman or girl was brought back to Moscow. Although Asch sheds little light on her life in Russia, he does tell us that she died from venereal disease. An anatomy professor in Moscow had performed an autopsy before forwarding the skull to Asch in St. Petersburg. Ironically, perhaps, the woman whose skull gave white people a name had been a sex slave in Moscow, like thousands of her compatriots in Russia and the Ottoman empire.

Blumenbach labeled his prize skull “beautiful” and “female Georgian,” going on to call the human variety it inspired “Caucasian,” a mysterious slippage he did not explain. Why not call it “Georgian,” we may ask, since the skull came from Georgia? The answer may lie in North America, where the newly formed United States already included a state called Georgia and, presumably, people called Georgians.

*

At any rate, during Blumenbach’s time, the notion of “Caucasian” achieved wide circulation.