The Grand Alliance (62 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

On the evening of the twenty-eighth, Rear-Admiral King had sailed, with the

Phoebe, Perth, Calcutta, Coventry,

the assaultship

Glengyle,

and three destroyers, for Sphakia. On The Grand Alliance

376

the night of the twenty-ninth about six thousand men were embarked there without interference, the

Glengyle’s

landing-craft greatly helping the work. By 3.20 A.M. the whole body was on its way back, and, though attacked three times during the thirtieth, reached Alexandria safely. Only the cruiser

Perth

was damaged, by a hit in a boiler-room. This good luck was due to the R.A.F. fighters, who, few though they were, broke up more than one attack before they struck home. It was thought that the night of the twenty-ninth-thirtieth would be the last for trying, but during the twenty-ninth it was felt that the situation was less desperate than it had seemed. Accordingly, on the morning of the thirtieth, Captain Arliss once more sailed for Sphakia, with four destroyers. Two of these had to return, but he continued with the

Napier

and

Nizam

(a destroyer given to us by the Prince and people of Hyderabad), and successfully embarked over fifteen hundred troops. Both ships were damaged by near-misses on the return voyage, but reached Alexandria safely. The King of Greece, after many perils, had been brought off with the British Minister a few days earlier. That night also General Freyberg was evacuated by air on instructions from the Commanders-in-Chief.

On May 30 a final effort was ordered to bring out the remaining troops. It was thought that the numbers at Sphakia did not now exceed three thousand men, but later information showed that there were more than double that number. Rear-Admiral King sailed again on the morning of the thirty-first, with the

Phoebe, Abdiel,

and three destroyers. They could not hope to carry all, but Admiral Cunningham ordered the ships to be filled to the utmost. At the same time the Admiralty were told that this would be the last night of evacuation. The embarkation went well, and the ships sailed again at 3 A.M. on June 1, carrying nearly

The Grand Alliance

377

four thousand troops safely to Alexandria. The cruiser

Calcutta,

sent out to help them in, was bombed and sunk within a hundred miles of Alexandria.

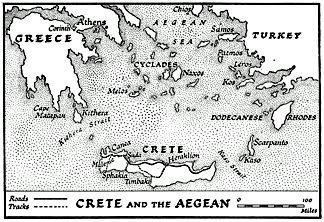

Upward of five thousand British and Imperial troops were left somewhere in Crete, and were authorised by General Wavell to capitulate. Many individuals, however, dispersed in the mountainous island, which is a hundred and sixty miles long. They and the Greek soldiers were succoured by the villagers and country folk, who were mercilessly punished whenever detected. Barbarous reprisals were made upon innocent or valiant peasants, who were shot by.

twenties and thirties. It was for this reason that I proposed to the Supreme War Council three years later, in 1944, that local crimes should be locally judged, and the accused persons sent back for trial on the spot. This principle was accepted, and some of the out standing debts were paid.

Sixteen thousand five hundred men were brought safely back to Egypt. These were almost entirely British and Imperial troops. Nearly a thousand more were helped to escape later by various commando enterprises. Our losses were about thirteen thousand killed, wounded, and taken prisoners. To these must be added nearly two thousand naval casualties. Since the war more than four thousand German graves have been counted in the area of Maleme and Suda Bay; another thousand at Retimo and Heraklion.

Besides these were the very large but unknown numbers drowned at sea, and those who later died of wounds in Greece. In all, the enemy must have suffered casualties in killed and wounded of well over fifteen thousand. About a hundred and seventy troop-carrying aircraft were lost or

The Grand Alliance

378

heavily damaged. But the price they paid for their victory cannot be measured by the slaughter.

The Battle of Crete is an example of the decisive results that may emerge from hard and well-sustained fighting apart from manoeuvring for strategic positions. We did not know how many parachute divisions the Germans had.

Indeed, as the result of what happened in Crete, we made preparations, as will presently be described, for home defence against four or five of these audacious airborne divisions; and later still we and the Americans reproduced them ourselves on an even larger scale. But in fact the 7th Airborne Division was the only one which Goering had. This division was destroyed in the Battle of Crete. Upward of five thousand of his bravest men were killed, and the whole structure of this organisation was irretrievably broken. It never appeared again in any effective form. The New Zealanders and other British, Imperial, and Greek troops who fought in the confused, disheartening, and vain struggle for Crete may feel that they played a definite part in an event which brought us far-reaching relief at a hingeing moment.

The Grand Alliance

379

The German losses of their highest class fighting men removed a formidable air and parachute weapon from all further part in immediate events in the Middle East. Goering gained only a Pyrrhic victory in Crete; for the forces he expended there might easily have given him Cyprus, Iraq, Syria, and even perhaps Persia. These troops were the very kind needed to overrun large wavering regions where no serious resistance would have been encountered. He was foolish to cast away such almost measureless opportunities and irreplaceable forces in a mortal struggle, often hand-to-hand, with the warriors of the British Empire.

We now have in our possession the “battle report” of the XIth Air Corps, of which the 7th Airborne Division was a part. When we recall the severe criticism and self-criticism to which our arrangements were subjected, it is interesting to read the other side.

The Grand Alliance

380

British land forces in Crete [said the Germans] were about three times the strength which had been assumed. The area of operations on the island had been prepared for defence with the greatest care and by every possible means…. All works were camouflaged with great skill…. The failure, owing to lack of information, to appreciate correctly the enemy situation endangered the attack of the XIth Air Corps and resulted in exceptionally high and bloody losses.

In the German report of their examination of our prisoners of war the following note occurs, which, in my gratitude to those unknown friends, I venture to quote: As regards the spirit and morale of the British troops, it is worth mentioning that in spite of the many setbacks to the conduct of the war there remains, generally, absolute confidence in Churchill.

The naval position in the Mediterranean was, on paper at least, gravely affected by our losses in the battle and evacuation of Crete. The Battle of Matapan on March 28

had for the time being driven the Italian Fleet into its harbours. But now new, heavy losses had fallen upon our Fleet. On the morrow of Crete Admiral Cunningham had ready for service only two battleships, three cruisers, and seventeen destroyers. Nine other cruisers and destroyers were under repair in Egypt, but the battleships

Warspite

and

Barham

and his only aircraft-carrier, the

Formidable,

besides several other vessels, would have to leave Alexandria for repair elsewhere. Three cruisers and six destroyers had been lost. Reinforcements must be sent without delay to restore the balance. But, as will presently be recorded, still further misfortunes were in store. The period which we now had to face offered to the Italians their The Grand Alliance

381

best chance of challenging our dubious control of the Eastern Mediterranean, with all that this involved. We could not tell they would not seize it.

The Grand Alliance

382

17

The Fate of the “Bismarck”

Danger in the Atlantic — The “Bismarck” and

“Prim Eugen” at Sea, May

20 —

The Denmark

Strait — The Destruction of the “Hood,” May

24 —

The “Bismarck” Turns South — Suspense at

Chequers — The “Prinz Eugen” Escapes —

Torpedo Hit on “Bismarck” at Midnight — Contact

Lost on May

25 —

But Regained on the Twenty-Sixth — Shortage of Fuel — The “Sheffield” and

the “Ark Royal” — The “Bismarck” Out of Control

— Captain Vian’s Destroyers — “Rodney” Strikes,

May

27 —

My Report to the House — Credit for

All — My Telegram to President Roosevelt.

A

FTER THE GREEK COLLAPSE, while all was uncertain in the Western Desert, and the desperate battle in Crete was turning heavily against us, a naval episode of the highest consequence supervened in the Atlantic.

Besides the constant struggle with the U-boats, surface raiders had already cost us over three-quarters of a million tons of shipping. The two enemy battle-cruisers

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau

and the cruiser

Hipper

remained poised at Brest under the protection of their powerful A.A. batteries, and no one could tell when they would again molest our trade routes. By the middle of May there were signs that the new battleship

Bismarck,

possibly accompanied by the new eight-inch-gun cruiser

Prinz Eugen,

would soon be thrown into the fight. A The Grand Alliance