The Grand Alliance (139 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

2. We could not get the words “or authorities”

inserted in the last paragraph of the Declaration, as

Litvinov is a mere automaton, evidently frightened out

of his wits after what he has gone through. This can be

covered by an exchange of letters making clear that the

word “Nations” covers authorities such as the Free

French, or insurgent organisations which may arise in

Spain, in North Africa, or in Germany itself. Settlement

was imperative because, with nearly thirty Powers

already informed, leakage was certain. President was

also very keen on January 1.

3. Speed was also essential in settling letter of

instructions to Wavell. Here again it was necessary to

defer to American views, observing we are no longer

single, but married. I personally am in favour of Burma

being included in Wavell’s operational sphere; but of

The Grand Alliance

835

course the local Commander-in-Chief Burma will be

based on India and will have a job of his own to do. He

will have to get into friendly touch with Chiang Kai-shek,

upon whom, it appears, Wavell and Brett made a none

too good impression.

4. The heavy American troop and air force movements into Northern Ireland are to begin at once, and

we are now beating about for the shipping necessary to

mount “Super-Gymnast,” if possible, during their

currency.

5. We live here as a big family, in the greatest

intimacy and informality, and I have formed the very

highest regard and admiration for the President. His

breadth of view, resolution, and his loyalty to the

common cause are beyond all praise. There is not the

slightest sign here of excitement or worry about the

opening misfortunes, which are taken as a matter of

course and to be retrieved by the marshalling of overwhelming forces of every kind. There will of course be a

row in public presently.

6. Please thank the War Cabinet for their very kind

New Year’s message. I am so glad you like what I said

in Canada. My reception there was moving.

It may well be thought by future historians that the most valuable and lasting result of our first Washington Conference – “Arcadia,” as it was code-named – was the setting up of the now famous “Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee.” Its headquarters were in Washington, but since the British Chiefs of Staff had to live close to their own Government they were represented by high officers stationed there permanently. These representatives were in daily, indeed hourly, touch with London, and were thus able to state and explain the views of the British Chiefs of Staff to their United States colleagues on any and every war problem at any time of the day or night. The frequent The Grand Alliance

836

conferences that were held in various parts of the world –

Casablanca, Washington, Quebec, Teheran, Cairo, Malta, and the Crimea – brought the principals themselves together for sometimes as much as a fortnight. Of the two hundred formal meetings held by the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee during the war no fewer than eighty-nine were at these conferences; and it was at these full-dress meetings that the majority of the most important decisions were taken.

The usual procedure was that in the early morning each Chiefs of Staff Committee met among themselves. Later in the day the two teams met and became one; and often they would have a further combined meeting in the evening.

They considered the whole conduct of the war, and submitted agreed recommendations to the President and me. Our own direct discussions had of course gone on meanwhile by talks or telegrams, and we were in intimate contact with our own Staff. The proposals of the professional advisers were then considered in plenary meetings, and orders given accordingly to all commanders in the field. However sharp the conflict of views at the Combined Chiefs of Staff meetings, however frank and even heated the argument, sincere loyalty to the common cause prevailed over national or personal interests.

Decisions once reached and approved by the heads of Governments were pursued by all with perfect loyalty, especially by those whose original opinions had been overruled. There was never a failure to reach effective agreement for action, or to send clear instructions to the commanders in every theatre. Every executive officer knew that the orders he received bore with them the combined conception and expert authority of both Governments.

There never was a more serviceable war machinery

The Grand Alliance

837

established among allies, and I rejoice that in fact if not in form it continues to this day.

The Russians were not represented on the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee. They had a far-distant, single, independent front, and there was neither need nor means of Staff integration. It was sufficient that we should know the general sweep and timing of their movements and that they should know ours. In these matters we kept in as close touch with them as they permitted. I shall in due course describe the personal visits which I paid to Moscow. And at Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam the Chiefs of Staff of all three nations met round the table.

The enjoyment of a common language was of course a supreme advantage in all British and American discussions.

The delays and often partial misunderstandings which occur when interpreters are used were avoided. There were however differences of expression, which in the early days led to an amusing incident. The British Staff prepared a paper which they wished to raise as a matter of urgency, and informed their American colleagues that they wished to

“table it.” To the American Staff “tabling” a paper meant putting it away in a drawer and forgetting it. A long and even acrimonious argument ensued before both parties realised that they were agreed on the merits and wanted the same thing.

I have described how Field-Marshall Dill, though no longer Chief of the Imperial General Staff, had come with us in the

Duke of York.

He had played his full part in all the discussions, not only afloat, but even more when we met the American leaders. I at once perceived that his prestige and influence with them was upon the highest level. No

The Grand Alliance

838

British officer we sent across the Atlantic during the war ever acquired American esteem and confidence in an equal degree. His personality, discretion, and tact gained him almost at once the confidence of the President. At the same time he established a true comradeship and private friendship with General Marshall.

Immense expansions were ordered in the production sphere. In all these Beaverbrook was a potent impulse. The official American history of their industrial mobilisation for war

1

bears generous testimony to this. Donald Nelson, the Executive Director of American War Production, had already made gigantic plans. “But,” says the American account, “the need for boldness had been dramatically impressed upon Nelson by Lord Beaverbrook on December 29….” What happened is best portrayed by Mr. Nelson’s own words:

Lord Beaverbrook emphasised the fact that we must set our production sights much higher than for the year 1942, in order to cope with a resourceful and determined enemy. He pointed out that we had as yet no experience in the losses of material incidental to a war of the kind we are now fighting…. He emphasised over and over again the fact that we should set our sights higher in planning for production of the necessary war material. For instance, he thinks we should plan for the production of forty-five thousand tanks in 1942 against Mr. Knudsen’s estimate of thirty thousand.

The American account continues:

The ferment Lord Beaverbrook was instilling in the mind of Nelson he was also imparting to the President.

In a note to the President Lord Beaverbrook set the expected 1942 production of the United States, the The Grand Alliance

839

United Kingdom, and Canada against British, Russian, and American requirements. The comparison exposed tremendous deficits in 1942 planned production. For tanks these deficits were 10,500; for aircraft 26,730; for artillery 22,600; and for rifles 1,600,000. Production targets had to be increased, wrote Lord Beaverbrook, and he pinned his faith on their realisation in “the immense possibilities of American industry.” Production goals for 1942 should include 45,000 tanks, 17,700 antiaircraft guns, 24,000 fighter planes, and double the quantity of anti-aircraft guns then programmed, including all contemplated increases.

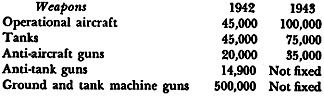

The outcome was a set of production objective whose magnitude exceeded even those Nelson had proposed. The President was convinced that the concept of our industrial capacity must be completely overhauled…. He directed the fulfilment of a munitions schedule calling for 45,000 combat aircraft, 45,000

tanks, 20,000 anti-aircraft guns, 14,900 anti-aircraft guns, and 500,000 machine-guns in 1942.

I reported all this good news home.

Prime Minister to Lord

4 Jan. 42

Privy Seal

A series of meetings has been held on supply

issues. These were presided over by the President

himself and the Vice-President. Negotiations were

carried forward and discussions of details took place

every day. Then on Friday there was a meeting presided over by the President and myself. There were two

meetings on Saturday. Final conclusions were:

It was decided to raise United States output of

merchant shipping in 1942 to 8,000,000 tons deadweight and in 1943 to 10,000,000 tons deadweight.

New 1942 programme is increase in production of one-third.

War weapons programmes for 1942 and 1943 were

determined as follows: