The Good and Evil Serpent (44 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

These comments have been reserved until this point in the presentation of our discoveries. Many of our earlier insights and suggestions were judiciously informed and based on such clear insight into the complex meaning of ancient serpent symbolism. Here we have proof, in clear prose, that the snake contained the most spirit and fire of all reptiles, lacks feet (contrast some depictions of snakes with feet), lives the longest of all reptiles, and regains its youth each time it sheds its skin. In fact, the snake is immortal; it does not die unless it is hit the way Hercules pounded it.

Philo of Byblos continues by quoting Epeeis, who claims that the “first and holiest being is the serpent which has the form of a falcon and is very pleasing” (815.18).

SUMMARY

We have now been able to establish the first three criteria specified in the introductory chapters: (1) The serpent or snake is clearly often a good symbol in world cultures. (2) The serpent was admired in antiquity especially in Old Testament times and the Second Temple Period. (3) The serpent was appreciated in the Greek and Roman periods, especially before and during the time that the Fourth Gospel was composed and edited.

What is the most important or prevalent meaning of the serpent in the Greek and Roman periods? Any answer would depend on when and where one focused one’s attention. Throughout “the known world” (and even elsewhere, in Mexico and South America, as well as among the Native Americans at that time, for example) the serpent frequently denoted health, healing, and the hope of a new and better life. The supreme example is in the pervasive Asclepian cult.

A thorough survey of serpent symbolism needs to move behind the symbolic and religious categories and seek to penetrate the world in which such symbols and religious motifs were given life. Perceiving how important religious symbolism was in antiquity, we need to grasp that the serpent was also a friend, like the dog in American homes today. As Pliny states in his

Natural History

, the Greeks and Romans often had serpents as household pets: “And a snake is commonly kept as a pet even in our homes.”

414

It has become clear that ophidian or anguine symbolism was prevalent in the ancient Greek and Roman world. These symbols were on statues and friezes in public buildings and temples and even in private homes. They circulated throughout the Levant and elsewhere and were often worn as jewelry. For example, in the fourth century

BCE

the two dominant armies and cultures were Persian and Greek, yet each stressed the symbolism of the serpent. Two silver bracelets have been recovered, but not published until now.

415

One is Persian and shows two serpents, with triangular heads, looking at each other at the point at which the circle would have been completed. Another silver bracelet is Greek. It is more delicate and refined, but again the circle is open so that two serpents, with protruding eyes, can look at each other. Both bracelets are from the fourth century

BCE

and before the defeat of the Persians by Alexander the Great, with the Persian one conceivably slightly earlier. As one studies the two bracelets with ophidian images, one is impressed at the common culture shared by Persians and Greeks.

The bracelet on the left in

Fig. 62

is Greek; the one on the right is Persian. Observe that in each ophidian object the eyes of the animal are highlighted. It is significant that two artists, one each from two warring cultures, chose the serpent for a symbol. Both pieces of jewelry indicate snakes or dragons at the end of each circle. What do the animals signify? We now know the serpents are not merely decorations. They may symbolize or evoke thoughts about Ouroboros, the caduceus, and perhaps something more.

Figure 62

. Two Silver Serpent Bracelets. JHC Collection

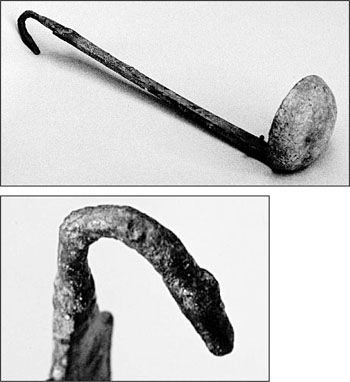

The bronze ladle in

Fig. 63

was found in the Levant.

416

It most likely dates from the early Roman Period. Numerous examples of this type of ladle are found in world-class museums. Large bowls of wine mixed with water were served by the host or an attractive slave. The ladle was used to convey the drinks to the guests. No ladle that I have seen has a serpent on the curved upper part. The animals on the handle are usually ducks or deer. The present example clearly shows a serpent. No ears are indicated, and the eyes and face are those we have already seen numerous times.

Figure 63.

Bronze Ladle (and detail at left). Roman Period. Levant. JHC Collection

An approximation of what the symbol of the serpent might have denoted, at least to some ancient Greeks and Romans, and at least sometime during their lives, might be surmised by looking at the features given to the serpents in the virtual myriad of realia from antiquity. The wings denote the serpents’ swiftness, mobility, and elusiveness. As W. Burkert claims, the serpents symbolize what is “ubiquitous and unassailable.”

417

The serpent sometimes has a large mouth, pricking the fear of humans who in primordial times lived with the anguish that they might be swallowed whole (like Jonah) or devoured by a dragon-serpent beast. The goatee or beard probably denoted that the serpent was wise and cunning. The anguinepedes of the Giants and other creatures denote their ability to be elusive as well as to skim over all surfaces, earth and water. Reflection on this symbolic meaning is enhanced by Cicero’s remark in

De natura deorum.

He asserts that serpents born on land immediately take to the water, like sea turtles (2.124).

418

Symbolism can be abused, especially when it is within the realm of religion or spirituality, as it was surely in the Hellenic and Hellenistic Period. There were charlatans who made a profit from the odd mixture of gods and serpents.

Alexander of Abonuteichos (fl. c. 150#x2013;70

CE

) is little known, except in the emotionally distorting satire of Lucian. According to Lucian, he “became the most perfect rascal of all those who have been notorious far and wide for villainy.”

419

Lucian thus names the arch villains, but each pales in comparison with Alexander. This false priest of Asclepius played on the fears of the masses. He manipulated their need to believe in myths. He provided what they wanted (but not what they needed). For a meager sum, Alexander purchased a serpent from Pella where there were many “immense serpents” that were tame and gentle. He had a devious plan.

that were tame and gentle. He had a devious plan.

With another charlatan, Alexander would masquerade under the guise of representing the two great tyrants of humans: hope and fear. They founded “a prophetic shrine and oracle.” They schemed to become prosperous and rich. In the temple of Apollo in Chalcedon they buried bronze tablets “which said that very soon Asclepius, with his father Apollo,” would live in Abonuteichos. Before his companion died, perhaps from the bite of a viper, he and Alexander had constructed “a serpent’s head of linen, which had something of a human look, was all painted up, and appeared very lifelike. It would open and close its mouth by means of horsehairs, and a forked black tongue like a snake’s, also controlled by horsehairs, would dart out.”

Subsequently, Alexander secretes a goose egg in which he had hidden a newly born snake in the foundation of a temple being built in expectation of the appearance of Asclepius and Apollo. Naturally, the next day he causes a disturbance and exposes the egg and the serpent. He then proclaims that he held Asclepius in his hand. He takes the god to his home, before the watchful eyes of the crowds. When, some days later, the crowds come to his home, he lets them see him sitting with the immense snake from Pella, hiding only the head. The head that the crowd saw was the one made of linen. The crowds believed in a miracle, since in so short a time a tiny serpent became an immense serpent “with a human face.” Not only the ancients who read Lucian would have denounced the pseudoprophet of Asclepius. Most would have known he was an imposter. Thus, they would have continued to honor, adore, and worship Asclepius and his “true prophets.”

CONCLUSION

This survey has highlighted serpent symbolism in numerous cultures, from Minoan Crete to Asclepian Epidaurus. We have learned that the serpent appears to have been the most complex and pervasive symbol in antiquity. It not only denoted evil but also, and primarily, symbolized good. It dominated especially in the Asclepian cult.

When Christianity became the dominant political force, beginning in the early fourth century

CE

, it was empowered to relegate other religions. Then, many former positive symbols were demoted to a negative connotation and denotation.

420

Constantine the Great banned most magicians because “paganism” was still deep in his court and army. He thus forbade maleficent magic, but permitted medical and agricultural magic.

421

His edict against pagan sacrifice on 17 December 321 was a prolegomenon to the universally observed Theodosian Code of 438, which proscribed any sacrifices to pagan deities.

422

Although, there were some intellectuals, like Porphyry (232/33#x2013;305

CE

), who perceived the

daimones

to be evil,

423

“the demon” was usually considered good in Hellenic, Hellenistic, and Roman society. Socrates (469#x2013; 399

BCE

) claimed that a good “demon” played a major role in his life. He contended that the voice that had guided him since his youth was a divine demon ( ).

).

424

Plato, Xenophon, and Aristophanes attested that Socrates was under the power of “a demon”; that is, a good spirit. K. Kleve examines the evidence and concludes that Socrates thus should be seen not as an intellectual but a religious figure.

425