The Good and Evil Serpent (20 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Mareshah (Tel Sandahanna)

Mareshah is a site in Judah about halfway between Beer-sheba and Ramleh, just north of Gezer. The town seems to have originated in the Iron Age; it was conquered in 701

BCE

by Sennacherib.

In the third and second centuries

BCE

, Idumeans, Sidonians, and Greeks buried their dead in the necropolis at Mareshah. Tombs I and II are rich with paintings. One scene shows a serpent rising up before a bull.

159

The exact meaning of the ophidian symbolism is far from clear. Is it conceivable that the artist was thinking about Mithraic mythology that has a serpent helping Mithra slay a bull? While this answer is possible, bulls and serpents were linked in non-Mithraic myths. A search for answers may be aided by iconography found elsewhere. For example, one should consider the vase in the form of a bull found in Luristan with a serpent looking out from a circular hole above the bull’s two front legs and another serpent gazing from behind the head.

160

Carmel

Mount Carmel is a long mountain range running southeast to northwest. At its southern end is Megiddo, and at its northern promontory that overlooks the Mediterranean Sea sits Shiqmona. Mount Carmel is thus the northwestern continuation of the Samaritan hills. Impressive prehistoric caves are found, especially on its southern flank, including Abu Usba, Skhul, Jamal, Sefunim, Tabun, Kebara, and el-Wad.

161

Mount Carmel is most famous because it is the site on which Elijah confronted Ahab and the prophets of Baal (1 Kgs 18:17–46). In the first century

BCE

, Alexander Jannaeus captured Mount Carmel

(Ant

. 13.396), but Pompey took it from the Hasmoneans and linked it with Acco

(War

3.35). In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, a temple to Zeus and an altar were situated there.

162

Figure 23

. The Carmel Aphrodite. Courtesy of the Israel Museum.

In 1929, fragments of a statuette were found on this famous mountain, recovered from the large cave named Magharat el Wad. The portrayal of Aphrodite (Venus) is unlike her embodiment in the famous Venus de Milo now prominently displayed in the Louvre in Paris

163

or her depictions on the Parthenon.

164

She is also dissimilar to the depiction of bare-breasted Aphrodite being born from the sea fully mature. That is, she is shown entirely nude, as in the following: the mirror in the Louvre that depicts her with Eros, the crouching Aphrodite in the Museo Nazionale Romano, the bathing Aphrodite from Rhodes, the Aphrodite from Cyrene in the Museo Nazionale Romano, the Aphrodite from Delos in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, and especially the Aphrodite created by the sculptor Praxiteles now in the Vatican.

165

In the Mount Carmel statuette, her weight is on her left leg, and her right leg is inclined forward.

The terra-cotta statuette was originally dated to the “late fourth or third century B.C.,”

166

but has been redated to the first century

CE

. While the statuette was rightly associated with Praxiteles (c. 370-c. 330

BCE

) because he was the first Greek to display the female body in full nudity, it is nevertheless a copy or an imitation from a later period.

167

Praxiteles’ statues were widely copied, and his style became internationally famous and influential. The Roman style, languid body, and elongated form place the statuette within the art of the first century

CE

or maybe slightly earlier.

168

The iconography does not indicate that the figure is a serpent goddess. She is clearly Aphrodite. Her weight is on her left foot. Her left hand seems to rest on something to her left, now worn away. What is unique and highly significant for us about this statuette of Aphrodite? This is the only representation of Aphrodite, as far as I know, that has a snake on her body.

On her right leg she wears an anklet. On this leg, above the knee, and on the thigh is carved a serpent. The serpent appears from behind the right thigh and curls upward. The serpent’s head is well shaped. The artist placed no features on the serpent; there are no dots to signify skin or eyes. One cannot be certain how the head of the snake originally looked since it is badly worn. Are we to imagine something like a serpent garter?

169

What is the meaning of the serpent symbolism? The “serpent garter” probably meant to denote the sexual attractiveness of the female, but it could also evoke images of beauty, as well as the erect phallus, fertility, and power. We have already seen that the rampant tendency to interpret the serpent, only and always, as phallic or a symbol meaning only or primarily eroticism (as, e.g., in the publications by P. Diel)

170

is misleading and not perceptive of the extensive meanings of snake symbolism in an-tiquity.

171

Of course, one of the meanings of the serpent is the phallus or eroticism.

172

The sculpture is on public display in the Israel Museum. It is very similar to the figurine of Aphrodite found at Dardanos and dated to the second century

BCE

.

173

This figurine also has a serpent as a garter belt, but it is on the left thigh. Once again, the head of the serpent is not directed to the pubic area; in fact, it is turned away from the woman. Another serpent is depicted as coiled rings on the upper left arm.

174

The statuette of Aphrodite at Dardanos with the serpent’s head turned away from the attractive body should warn those seeking to discern the meaning of serpent symbolism that the Freudian approach is often not suggested by the iconography, which may resist such sexual interpretations.

Another marble statue is similar to the Carmel Aphrodite. Again Aphrodite is completely nude. She has a snake bracelet on her right hand. No eyes, mouth, or skin are depicted. The head faces downward, following the fall of the arm, which covers her pubic area. The finish of the surface and the modeling of the pierced ears indicate, perhaps, the late Hellenistic Period or the early Roman Period.

175

Aphrodite was also revered in Akko, only a little north of Carmel. We know this from a passage in the Mishnah. Rabbi Gamaliel II (late first century

CE

) was ostensibly asked by a non-Jew in the baths at Akko (Acre) how he could explain entering a bath with pagan idols. Gamaliel replied, “I came not within her limits: she came within mine! They do not say, ‘Let us make a bath for Aphrodite,’ but ‘Let us make an Aphrodite as an adornment for the bath.’ … thus what is treated as a god is forbidden, but what is not treated as a god is permitted”

(Avodah Zarah

3:4, Danby). This passage is quite remarkable. It not only specifies that in the first century

CE

there was a statue of Aphrodite at Akko, but that the intention of an author is not to be confused with the meaning supplied by an observer. In this case, the two perspectives are antithetical. The author depicted a statue of the goddess Aphrodite, but Gamaliel dismissed the sculpture as merely a decoration.

It is clear that Aphrodite did not primarily represent sex and eroticism. She was the embodiment of beauty. L. Kreuz has explored the genesis of the conception of beauty by focusing on Aphrodite in antiquity.

176

The statuette discovered on Mount Carmel depicts Aphrodite as the one who symbolizes beauty and aesthetics, especially as contemplated by some at the beginning of the Common Era. The serpent is thus a positive symbol, perhaps of goodness, life, and beauty.

Summary

This survey of snake objects found in controlled excavations grounds our reflections on serpent symbology. Since many of the snake objects or images were discovered in or near temples or cult settings, it is certain that the serpent denoted a god, a divinity; it also denoted other human aspirations, needs, and appreciations, including—but not limited to—beauty, power, fertility, rejuvenation, royalty, the cosmos, and life. Since the serpent is often carved on the top of vessels that would have contained water, milk, or wine, it symbolized the divine protector. I have not found what will become so obvious when we study ophidian symbolism in the Asclepian cult; that is, I have not found clear evidence from controlled excavations that the serpent denoted, or connoted, rejuvenation and immortality. Perhaps rejuvenation and new life are reflected on the snake stands and altars found in the Canaanite sites, especially at Beth Shan.

EGYPTIAN SERPENT ICONOGRAPHY: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND LITERARY EVIDENCE

Early ophidian symbolism takes stunning form among the Egyptians sometime around 3000

BCE

. Even their language is influenced by serpent iconography; hieroglyphs evolved from pictorial art. In the Middle Egyptian language of 2240 to 1740

BCE

, which continued on monuments and in some texts into the Roman Period, two of the twenty-four phonograms are the symbol of a snake: the sound

f

is represented by a line drawing of a horned viper and

d

by a snake in the form of a uraeus.

177

The study of Egyptian serpent iconography is too well known today, throughout the world, to warrant anything but a summary. Serpents are featured on monuments, on thrones, in stelae, and just about everywhere in ancient Egypt.

178

As E. A. Wallis Budge of the British Museum stated in 1911: “The serpent was either a power for good or the incarnation of diabolical cunning and wickedness.”

179

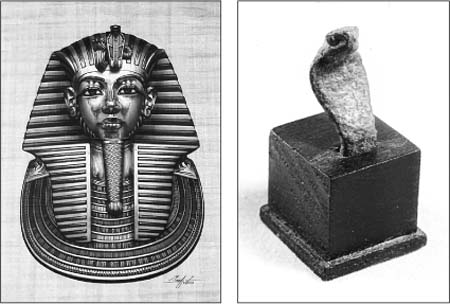

Perhaps Egyptian serpent iconography is well known not only because of the vast number of tomes, scholarly and popular, but because of the pervasive image of the gold mask of Tutankhamen with the noticeably raised cobra. The cobra was an ideal choice for the creature who would guard the pharaoh. The Egyptians observed that the cobra had no eyelids and thus would always be awake to guard the pharaoh, a god on earth. The uraeus probably signified kingship, power, royalty, and divinity.

180

Figures 24

and

25

are two striking examples of the uraeus, with the cobra upraised and placed on the head of Tutankhamen and later depicted as a bronze figure. The latter example was found in or near Jerusalem, dating from the Roman Period. What did the uraeus symbolize? In the Strasbourg Musée Archéologique we are told, “The uraeus personifies the eye of Re which destroys enemies by fire. The royal crown with the uraeus should be identified with the eye of Re.”

181

One of the most impressive, but little known, examples of ophidian iconography is found in the catacombs of Kom el-Shuqafa in Alexandria. They date from the first century

CE

. The doorway to the burial chamber is filled with serpent symbolism. Note the words of Jean-Yves Empereur in

Alexandria Rediscovered:

182

To enter the burial chamber, one has to pass through a doorway above which there is a winged disk under a

frieze of cobras

. On either side of it are circular shields covered with scales and with a

Medusa

head in the center (to “petrify” tomb-robbers), and

two snakes (representing the Agathodaimon, the benevolent deity)

, wearing the double crown of Egypt and coiled around

the caduceus of Hermes

and beribboned thyrsus of Dionysus, both Greek symbols. [Italics added to stress the ophidian symbology.]