The Good and Evil Serpent (39 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Most likely Asclepius was originally a man who, in the dim recesses of history, was remembered as a physician and who became semi-divine and eventually a full deity.

276

As L. R. Farnell stated, this deification of a physician is not so unusual; Im-hotep was once a real Egyptian physician who came to be considered a god.

277

As Pliny, in

Nat.

29.22, states, the Asclepian serpent

(anguis Aesculapius)

was brought from Epidaurus, where it originated, to Rome. Kerényi summarizes the most likely stages in the evolution of the Asclepian myth:

278

| Before 1000 BCE | | Flowering of the myth in Thessaly; Asclepius is a physician and teacher |

| 1000#x2013;600 BCE | | Time of Homer and Hesiod |

| 600#x2013;400 BCE | | Flowering of the Asclepian family at Cos [Hippocrates] |

| 500#x2013;300 BCE | | Beginning of the flowering of the Asclepian cult in Epidauros |

| 291 BCE | | The Asclepian cult comes to Rome (the island in the Tiber) |

Our concern is not with the origins of the Asclepian myth and cult. It is with the elevation of Asclepius to a full god, equal to Zeus, and the Asclepian serpent iconography and symbology. The evidence for this is abundant; note, for example, the ideas preserved on an Attic stone from the second century

CE

: “O Asklepios … O blessed one, O God of my longing…. Thou alone, O divine and blessed one, art mighty.”

279

Long before the first century

CE

, when the Fourth Gospel was composed, Asclepius was depicted with serpents as the god of healing. Not only was Asclepius deified, but physicians, who were unusually successful and thus revered, were deified as Asclepius.

280

Celsus (fl. c. 14#x2013;37

CE

), author of

De Medicina

, helps us understand the evolution of the Asclepian myth. He wrote that Asclepius was “celebrated as the most ancient authority” on medicine. He “was numbered among the gods [

in deorum numerum receptus est

]” because “he cultivated this science, as yet rude and vulgar, with a little more than common refinement.” His sons, Podalirius and Machaon, were not magicians or physicians who could heal all diseases. As Homer stated, during the Trojan War, they were able to heal battle wounds only “by the knife and medicaments.”

281

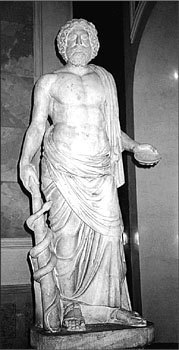

Figure 58.

A Statue of Asclepius with the Serpent Staff. Greek or Early Roman Period. Courtesy of the Hermitage. JHC

Asclepius appears to the Greeks and Romans as a serpent.

282

He usually is depicted with a staff around which a serpent is entwined.

283

This imaginative portrait of Asclepius dates as early as the fifth century, and perhaps sixth century,

BCE

. Marcus Aurelius (Roman emperor from 161 to 180

CE

), though he was imbued with Stoicism, occasionally thought of himself as Asclepius (actually Aesculapius), and liked to be seen as a god holding a staff like Asclepius’ staff. Asclepius is depicted with Telesphoros and with a serpent on a staff; the work dates from the second century

CE

.

284

Some guidance in perceiving the meaning of anguine symbols in the Asclepian cult is provided by texts. For example, Q. Ogulnius has a dream in which Asclepius appears; here are the pertinent words of Ovid (43

BCE

#x2013;17 or 18

CE

):

285

Fear not! I shall come and leave my shrine. Only look upon this serpent which twines about my staff [

hunc modo serpentem, baculum qui nexibus ambit

], and fix it on your sight that you may know it. I shall change myself to this, but shall be larger [

sed maior ero

] and shall seem as great as celestial bodies should be when they change.

286

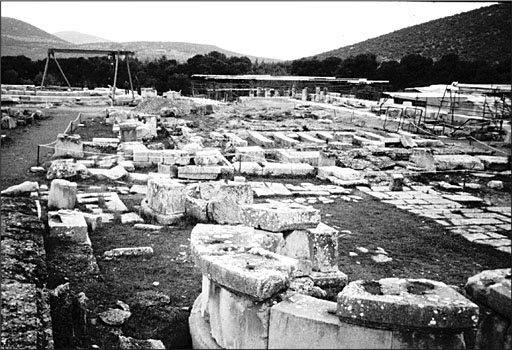

Figure 59.

The Asklepieion at Epidaurus. The Temple of Asclepius is in the foreground. JHC

Thus, the god of healing, Asclepius, was envisioned as a serpent by the contemporaries of the Fourth Evangelist.

Originally at Epidaurus in southern Greece and then after he came to Rome in 291

BCE

,

287

Asclepius became more and more a dominant god who was needed each day for health and healing. For example, one can think of the ancient retaining wall of Tiber Island. On it is etched the bust of Asclepius with a serpent on a staff.

288

Ancient Greek and Roman iconography and literature habitually portray Asclepius as a serpent.

289

Tame snakes considered sacred were fed by devotees at the shrines of Asclepius. From Athens comes an inscription that dates from the time of the composition of the Fourth Gospel. Note the words of the inscription: “to Asclepius: the celestial serpent of the gods.”

290

The adjective “celestial” is almost as important in the history of serpent iconography as “serpent.”

Worship and veneration of Asclepius were widespread in antiquity, especially in the first century

CE

. The evidence indicates that by the first century

CE

this “demigod” evolved in Western consciousness from being considered a mortal to a half-god and finally to a full god, perhaps the supreme deity. Clearly, in some centers of Western culture Asclepius was the most revered of all gods. Asclepius was finally identified with Zeus, and this belief seems to have been widespread in antiquity. When one considers how the ancients desired good health and yearned for healing against all forms of rampant illness, it is easy to imagine the worldwide adoration of the god of healing.

291

His shrines and cult celebrations were prevalent in the Greek and Roman world, especially, as we mentioned briefly, in Athens,

292

Epidaurus,

293

Cos,

294

Pergamum,

295

and Rome.

296

Edelstein, in the magisterial volumes on Asclepius, gives us a hint of the veneration of Asclepius:

Small wonder that the reverence paid him increased steadily, that his worship gradually spread over the entire ancient world, that he acquired a position of preeminence. Asclepius truly was a living deity, near to men’s hearts. It was he who now gave shelter to the more ancient gods and supported their failing might; it was his festivals that were still celebrated when those of other deities began to be forgotten.

297

It seems no exaggeration to think that in antiquity no god was more revered and had more devout followers than Asclepius.

298

That is important since the devotees in his cult elevated the positive meaning of the serpent.

299

The longevity of this cult is also noteworthy. It was influential from about the fifth century

BCE

to the middle of the fourth century

CE

.

The Fourth Evangelist lived in a cosmopolitan area and perhaps wrote in one of the major cities (conceivably originally in Jerusalem, and then edited in Ephesus or not far from Antioch). He and the members of the Johannine community may have been influenced by the depiction and adoration of Asclepius as a serpent. Since the Johannine community, while primarily Jewish, included Greeks (see Jn 12), one may ask: Were any members of the Johannine community converts from the Asclepian cult?

Is there any link between the use of “Savior” in the Fourth Gospel and the celebration of Asclepius as “Savior”? This name is frequently used for Asclepius,

300

and “Savior” ( ) appears on numerous coins that would have been held by the contemporaries of the Fourth Evangelist.

) appears on numerous coins that would have been held by the contemporaries of the Fourth Evangelist.

301

What then did the serpent and the staff symbolize in antiquity? In

De slangestaf van Asklepios als symbool van de Geneeskunde

, J. Schouten provides some thoughtful reflections. He understands the Asclepian symbolism of the serpent to denote the following:

Originally it was an independent chthonical symbol of the ever renewing and indestructible life of the earth. As such it was also the symbol of deliverance from disease, in other words: a healing symbol. It should be noted that in the antique view of life it is by no means a symbol in our modern sense, but rather an expression of direct experience of reality. [p. 184]

It is this in-depth indwelling of our phenomenal world that is so essential in perceiving the meaning of serpent symbolism. The serpent is of the earth and crawls on the earth. The snake does not pound the earth as horses or as we do when walking. The snake also often darts into and out of the earth.

What then does the serpent staff symbolize?

302

Again, listen to the reflections of Schouten: “From times immemorial the staff has been the symbol of vegetative growth: it represented the everlasting life of the earth in all its aspects; it therefore symbolized recovery from disease, in other words: deliverance from death” (p. 184). The serpent entwined around the staff symbolized what the human most required: health, healing from sickness and injuries, and protection from death.

In antiquity, artists often showed Asclepius with a serpent around a staff and a dog nearby. About 350

BCE

, a silver coin was minted at Epidaurus. It shows Asclepius with his right hand over a large serpent and a dog curled up under his throne.

303

A little earlier, an artist created a relief in Epidaurus that showed Asclepius with a dog between him and his two sons; quite surprisingly no serpent is depicted.

304

This iconography stems from the myth that Asclepius when a child was guarded by a dog and as a god was accompanied by a dog. In Greek mythology, the dog and the serpent were often conceived in similar ways; they both represented the underworld. A dog can represent a serpent.

305

In an earlier chapter we saw a bronze of Hermes or Mercury. The caduceus was held in his left hand. At his feet sits a dog. Excavations at Jericho proved the supposition that the dog was the first animal to be domesticated. In Egypt, the god Anubis appears as a dog. We have seen that a dog was chosen symbolically to guard the portals of the next world, the afterlife; it is called Cerberus.