The Good and Evil Serpent (14 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Twenty-third, the snake is physiologically and definitively unlike humans. It is thus something that can be seen as inhuman, subhuman, or superhuman. The snake cannot wink, laugh, or talk, but it can rapidly deliver a deadly dose of venom. Not only fear but also loathing often accompany thoughts related to the snake. The symbolisms here are numerous. They move within the world of folktales, legends, myths, and into the heart of religion and spirituality.

Twenty-fourth, the snake hibernates. That is, it enters into the earth for long periods. Where does it go? What is it doing? What is it learning? All these and many more reflections might spring to the mind of our primordial—certainly not primitive—ancestors. They did not simply assume that the snake was sleeping in its hibernaculum, as we dismiss through categorization of this rare phenomenon (it is not unique in the animal kingdom, but it is still a remarkable aspect of the snake’s life). This chthonic dimension of the snake would add to anguine symbolism the dimension of wisdom. It is clear, then, from this and previous observations, why the Egyptians, early Jews, and Jesus used the snake to symbolize wisdom.

Twenty-fifth, the snake appears slimy and cold. It is not warm and fluffy like a puppy; it is often disturbing to the touch. This feature adds to its demonic or diabolical features or symbolism. Thus, it is evident why the Babylonians

93

and many early Christians stressed that the snake was an embodiment of evil.

In Persian (or Iranian) thought there are two gods. Ahura Mazda is the Wise Lord, the Creator. Angra Mainyu (later called Ahriman) is the arch-demon, the one who causes destruction and woes. He lives in darkness and can appear as a youth, lizard, or snake. The hero Thraetaona can cure some sicknesses, like Asclepius, and struggles “against the evil done by the serpent.”

94

Ahura Mazda creates Mithra (Mithras), “the ruler of all countries,” who apparently conflates with Thraetaona and Vima (“the good shepherd”

[Vendidad

11.21], and the great hero within Persian mythology)—perhaps as “Manly Valor”—to slay “the horse-devouring, poisonous, yellowish-horned Serpent.”

95

In the Tauroctony, found virtually everywhere but not yet in Pompeii, Herculaneum,

96

or Iran, Mithra is depicted slaying the bull. A serpent is usually shown. Sometimes it is only on the ground, but at other times it is depicted biting the bull (or perhaps drinking its blood).

97

F. Cumont, the father of the modern study of Mithraism, read the Tauroctony in terms of Zoroastrian dualism, concluding that the snake is an evil creature.

98

This interpretation does not do justice to the vast and complex examples of the Tauroctony; sometimes the serpent helps Mithra.

99

Along with R. Merkelbach, I take the serpent to be a positive symbol in Mithraism.

100

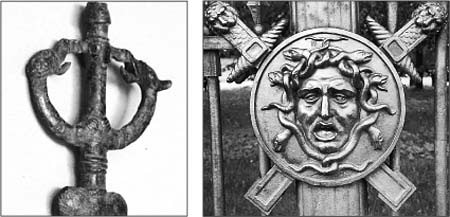

The bronze object in

Fig. 16

seems to be from the East or Luristan;

101

it may depict the two deities known to the Persians.

102

Figure 16

.

Left

. Bronze Dragons. Early Hellenistic Period. Found near Jerusalem. JHC Collection.

Figure 17

.

Right

. Medusa. The fence of the Summer Palace in St. Petersburg. JHC

Twenty-sixth, the snake digs in and around a garden, providing stimulus and growth. It also kills rodents and mice. Hence, it would be seen as the one who helps provide for the fertility of the soil. It is thus no wonder that the Greeks and Romans frequently used anguine symbolism to denote fruitfulness. It is also clear why the Rabbis advised Jews to have snakes in their gardens.

Twenty-seventh, the snake kills animals that are dangerous to humans, including mice and other rodents. Thus, the snake would most likely become perceived as the great guardian. This continues, for example, in the illustrated poem by Mechtilde Lichnowsky entitled “Die Dackeln und die Schlange.” Two puppies disobey their mother and dig an inviting hole in the garden, seeking to find something exciting there. They unearth a large serpent. The two puppies beg for mercy from this apparent monster who surely is about to devour them. The boa wraps herself around the babies. And, to the puppies’ surprise and delight, the boa brings them home to their mother

(Marbacher Magazin

64 [1993]). Perhaps this attribute of the snake as the protector or guardian helps to explain the presence of snakes on ancient jars and the ophidian symbolism of Medusa, as well as the stories and myths in which the snake is the guardian of treasure, most notably in the influential Syriac composition

Hymn of the Pearl

(second to fourth centuries

CE)

.

In Dante’s masterpiece, in Canto Nono 41, Medusa and others appear with “asps and vipers have they for hair”

(Serpentelli e ceraste avean per crine)

.

103

Figure 17

is a photograph of Medusa on the iron fence surrounding the Summer Palace in St. Petersburg.

To dismiss the perception that the serpent symbolizes “the guardian” only in ancient lore, literature, and iconography, I bring forward a rather recent poem. The poem is entitled “Die Schlange” and was composed by Friedrich Georg Jünger (18 9 8–19 77).

104

Here is the German and my translation:

Deine Schlange ist bei dir,

Die stille, die stumme.

Die alle Kammern des

Hauses kennt,

Deine Schlange ist bei dir.

Kehre wieder, was mag,

Die dich hütet im Umlauf.

[Your serpent is by you,

The silent one, the mute one.

Who knows every recess

in the house,

Your serpent is by you.

Come again, what may,

She guards you in life’s circles.]

This theme—”Your serpent is by you”—makes it clear that the serpent as the one who “guards you in life’s circles” is not an archaic thought or symbol.

Twenty-eighth, the snake can illustrate grandeur and majesty. No creature can be so awesomely regal as the upraised cobra with its hood extended.

105

Before such majestic power one feels total awe. Perhaps it can be categorized partly as divinity and partly as royalty. It is thus no wonder that Isaiah used this imagery in his throne vision and that the Egyptians used the uraeus to symbolize their belief that the pharaohs were divine kings.

Twenty-ninth, the snake does not smell. It cannot be discerned by smell, like the horse, dog, cat, lion, hyena, and especially the pig. That quality might add to its symbolic nature of being imperceptible and elusive. The

nabal

(Nachash) in Genesis 3 appears suddenly, without introduction; this “serpent” is not heard, seen, or smelled. No animal can compete with the snake for appearing unexpectedly and almost instantaneously. This characteristic of the snake would make it a good symbol for the appearance of the Spirit or God.

Thirtieth, some snakes look as if they are two-headed; that is, the head and tail are virtually indistinguishable.

106

This phenomenon would lead to numerous symbolic meanings. The snake may symbolize two opposites at once. The symbol most appropriate would be the caduceus.

As a complete circle, this two-headed snake could symbolize perfection, completeness, and the unity of time and the cosmos. It is no wonder that bracelets, especially in the Greek and Roman world, are intricately carved with snake heads at each end. The origin of the Ouoboros lies in this characteristic of the snake.

Also, some snakes do have two heads.

107

This may be caused by some genetic alteration or defect, but when ancients saw such a snake they would probably reflect about the symbolism it evoked. Anguine symbolism can thus denote duplicity, double-mindedness, the oneness of all duality, and other related concepts and ideas. Symbolizing sickness and health, the cause of evil or good fortune, the snake is behind the creation of the caduceus that appears often with Hermes and is placed on the coins of King Herod, as elsewhere.

Thirty-first, the snake is mysterious and unknown. Even today, much is still unknown.

108

Seeing a one-eyed snake, as a mutated

viper xanthina

,

109

can be an alarming experience. It evokes the mythology associated with Cyclops. The so-called combat dance or sex dance of the snake is often not between a male and female; it is now often recognized as a struggle between two male snakes that are competing for a mate. Sometimes her-petologists consider that the dance is a homosexual attempt of two males attempting to copulate. We are insufficiently informed about the longevity of snakes and about their potential length (since, unlike humans, snakes grow each year of their lives). Little is known today about the physiological changes that occur during hibernation, especially in the tropics. It is debated whether snakes swim or simply float and use their terrestrial means of locomotion to move them forward in the water. Thus, the snake is well chosen to symbolize the mystery that surrounds and accompanies human lives. Even as late as 1557, a French poet, probably inspired by ancient Greek tales, perhaps those well known and associated with Herodotus, could believe the following words: “Dangereuse est du serpente la nature, Qu’on voit voler près le Mont Sinai” (“Dangerous is the serpent by nature, which one observes flying near Mount Sinai”).

110

Finally, perhaps repeating some previous reflections, the snake is antisocial in the sense that a human cannot communicate with it and develop a relation with it. One can live together with a snake, but it is an odd companion whether in a prehistoric cave setting or in a modern garden. Stories abound of individuals who have pet boas that are treated royally for years and then swallow a child beloved by the owner. In Marrakech, I observed that snake handlers were constantly jumping back to avoid their pet, who was striking out at them. When they “kissed” the cobra, it was when the cobra had struck and was fully extended; moreover, it was held up and at a distance by the handler. There is no way to communicate with or develop something like “love” or “respect” with a snake. One cannot enjoy a relationship with a snake as one can with a dog.

SUMMARY

In seeking the physiological basis for the ophidian symbolism we shall be exploring, we have learned a vast amount about a remarkable creature. The snake has no arms, no legs, no ears, no eyelids, and only one functional lung. It cannot speak. It must swallow its food whole and is consigned to being carnivorous. When it falls asleep and hibernates, it cannot wake itself. It is totally dependent on its environment for heat. It cannot migrate, like the elephant, lion, or wildebeest to find food or water. Humans who have the physical limitations of a snake are immediately institutionalized;

111

but the snake is fearless, independent, must hunt only by ambush, and has survived from the time of the dinosaurs. Should we not recognize something special in this creature that we have been taught to hate (since such behavior has to be learned)?

In his

Patterns in Comparative Religion

, M. Eliade concluded that the “symbolism of the snake is somewhat confusing, but all the symbols are directed to the same central idea: it is immortal because it is continually reborn, and therefore it is a moon force, and as such can bestow fecundity, knowledge (that is, prophecy), and even immortality.”

112

Eliade may be commended for his focus, but he failed to represent all the various meanings of the symbol of the serpent.

113