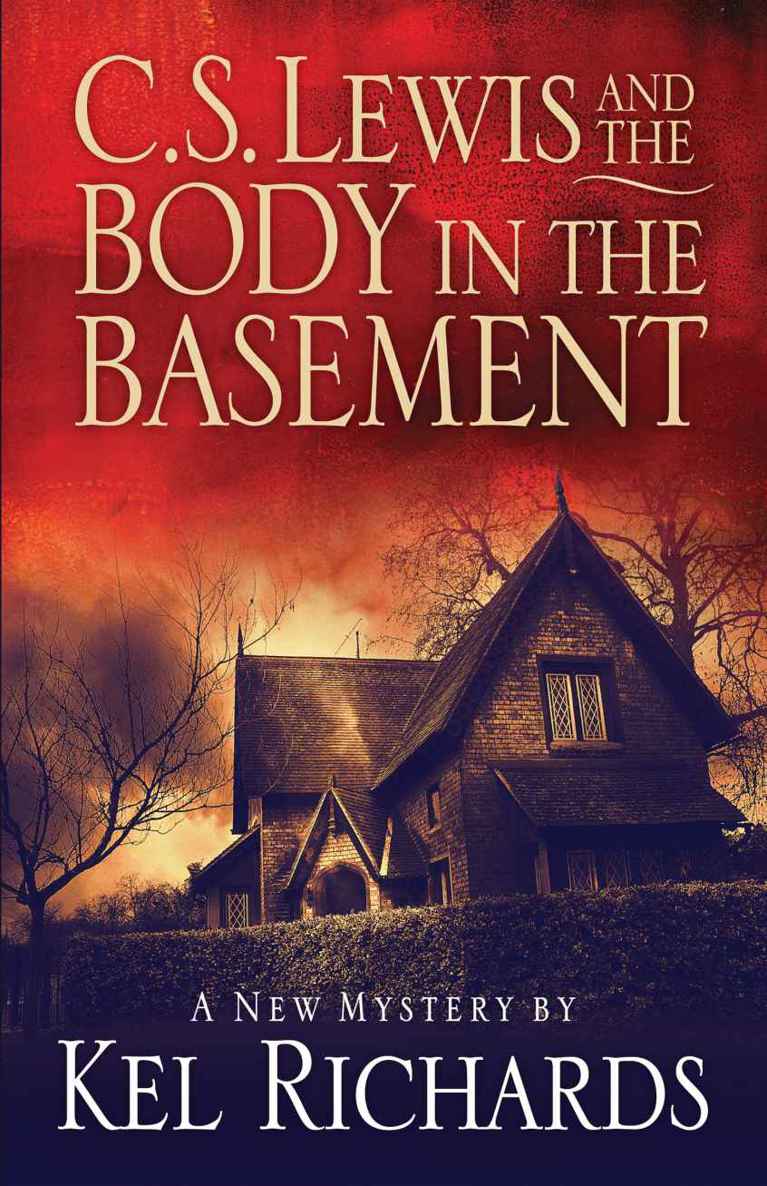

C S Lewis and the Body in the Basement (C S Lewis Mysteries Book 1)

Read C S Lewis and the Body in the Basement (C S Lewis Mysteries Book 1) Online

Authors: Kel Richards

C. S. Lewis and the Body in the Basement

Copyright © 2013 Kel Richards

First published 2013 by Strand Publishing

ISBN 978-1-921202-81-0

Distributed in Australia by:

KI Entertainment

Unit 31, 317–321 Woodpark Rd

Smithfield NSW 2164 Australia

Phone: (02) 9604 3600

Fax: (02) 9604 3699

Email:

[email protected]

Web:

www.kientertainment.com.au

This book is copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations for printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher.

Edited by Owen Salter

Cover design by Joy Lankshear

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

THE TIME: The summer of 1933; Trinity Term has just ended at Oxford University.

THE PLACE: Somewhere in Cambridgeshire, not far from the County of Midsomer.

‘Jack! Your wallet’s fallen into the fire!’ I shouted as I leaped forward and grabbed a pair of fire tongs. ‘I don’t know how long it’s been there,’ I grunted as I fished in among the burning logs and pulled out the black and crisp leather remains.

‘How did it fall into the fire?’ muttered Warnie, who through this wallet-rescuing rush had not shifted from his position leaning against the end of the mantelpiece. ‘The last time I saw it,’ he said, ‘was when I paid for our tea.’

The teapot, surrounded by cups and saucers, still sat on a small table near the fireplace. We’d ordered the tea while the pub prepared our breakfast. And Warnie had used his brother’s wallet to pay for the tea.

Warnie looked like a goggle-eyed goldfish swimming around its bowl looking for a way out. ‘And then I sat the wallet on the mantelpiece,’ he said in a dazed sort of way.

‘Perhaps not the safest place for it, old chap,’ said Jack gently.

‘Oh . . . oh, yes . . . see what you mean,’ Warnie mumbled as he took a sip from the large tea cup in his hand. ‘Ah, sorry about that, Jack.’

Warnie now looked both stunned and wary—like a cat that’s just been hit by a half-brick and thinks another might be on the way.

Jack said nothing but nudged the still smouldering wallet with the toe of his boot a bit further away from the flames.

The pub was

The Cricketers’ Arms

in the village of Plumwood. It was the first stop on our walking holiday. We’d chosen it as our starting point so that I could call into Plumwood Hall, the country home of Sir William Dyer, whose library I had undertaken to catalogue.

The day before I’d met the owner of Plumwood Hall for the first time. He turned out to be a thin man with a face like an untrustworthy monkey—the sort of monkey other monkeys would never lend money to. However, on this occasion he was offering to fork over some of the folding stuff, albeit a modest amount, so we had shaken hands on an agreement: me in my capacity as an unemployed recent graduate of Oxford University, and Sir William as the vastly wealthy manufacturer of

Dyer’s Digestive Biscuits

who had recently purchased the ancestral home of an impoverished baronet, including its large, and largely mysterious, library.

The wallet had now cooled enough to be touched and Jack picked it up. The leather was charred black, and when he opened it he found the notes it contained reduced to ashes.

‘Oh dear me,’ said Warnie, setting down his tea cup with a nervous clatter as if feeling the second half-brick hit. ‘Oh dear . . . Oh dear . . . that was all the money for our holiday, wasn’t it?’ he muttered, looking embarrassed.

‘All in notes,’ Jack confirmed, ‘no coins.’ In the gloomy tone that Jack adopted for all things financial he added, ‘Bankruptcy looms.’ Then seeing his brother’s woebegotten face he added, ‘Cheer up, old chap. These things happen.’

‘But how will we pay for things?’ Warnie asked. ‘I’m not carrying any money.’

‘I can pay for our accommodation here,’ I volunteered, ‘and for breakfast.’

‘Very kind of you, young Morris,’ said Jack. ‘And I’ll call into the nearest branch of the Capital and Counties Bank and make a withdrawal from my savings account.’

‘Where is the nearest branch of . . . whatever bank you said?’ I asked.

‘In Market Plumpton,’ Jack said, ‘a comfortable two hours walk from here.’ I was about to ask how he knew, but he anticipated my question by continuing, ‘I was in this district last year—on a walking holiday with Tollers and Dyson. I called into the Market Plumpton branch then.’

‘Your breakfast is ready, gentlemen,’ said the publican, walking into the room from the back parlour. ‘I’ve served it up in the snug . . . if you’ll follow me.’

Our unhappy adventure with Jack’s wallet had happened in the front bar parlour of

The Cricketers’ Arms

, so we now followed our host, one Alfred Rose by name, out to the small back private bar called the snug. There we found a table set for three, and three full English breakfasts already served and waiting.

‘This’ll cheer us up at any rate,’ grunted Warnie as he settled himself in his seat. ‘Eggs, bacon, sausages, toast—even some black pudding. That’s what I call a proper breakfast.’

And for the next few minutes we were fully occupied breaking our fast.

When mine host Alfred Rose returned, he was carrying a fresh pot of tea. The publican had a white, puffy face—rather like a lump of dough that had been sat on the windowsill to rise and was now about ready for the oven. It always felt slightly surprising when the puffy dough opened a mouth, smiled broadly and began to speak.

‘And what are your plans for the day, gentlemen?’ he asked in the hearty voice, and with the broad grin, of the professional publican.

‘We’re walking to Market Plumpton,’ I replied.

‘Well, don’t follow the road,’ Alfred suggested. ‘There’s a much more direct walking path over the hills and along the ridge top. Much more pleasant walking too,’ he added. ‘I’ll give you directions for finding the path when you’re ready to leave.’

He poured out fresh cups of tea for all of us, and then said, ‘But I thought you were heading north today. Why Market Plumpton?’

‘We have to call in to the bank,’ Jack explained as he finished the last of his egg and toast. ‘There’s a branch of the Capital and Counties Bank in Market Plumpton.’

The publican stopped pouring the tea and an earnest look came over his face, rather like a black cloud passing over the face of the sun. Shaking his head sadly he said, ‘Rather you than me, gentlemen.’

‘Why?’ I asked. ‘What on earth can be wrong with a bank? Or is it Market Plumpton itself you object to?’

‘No, no, it’s not the town. Lovely little market town it is. No, it’s the bank. That building has a dark history.’

‘What sort of dark history?’ asked Warnie, his words muffled by a mouthful of bacon.

‘Murder,’ hissed Alfred Rose as if whispering a dreadful secret in the manner of a stage villain in an overacted melodrama. ‘Murder—and a ghost.’

He was clearly dying to tell us the story so Jack invited him to do so.

The landlord set down the teapot, seated himself in a spare chair and leaned forward, his elbows on the table, his puffy face now flushed with colour and his small, black eyes shining like currants in the dough.

‘That bank is in a building that was once an old Georgian terrace house. Built as a gentleman’s residence it was,’ he began with the relish of a storyteller savouring a well-loved tale. ‘Some eighty or so years ago the owner was a certain Sir Rafael Black, a wool merchant. An awful man he was, a violent drunkard, rapidly working his way through his family fortune. His poor young wife, Lady Pamela, was terrified of him. He was a brutal man. Well, they do say that she took comfort in the arms of a handsome young footman.’

‘Do they say what this young footman’s name was?’ I asked. Having an interest in folklore, I wanted to see how much detail was included in this particular tale.

‘They say his Christian name was Boris, but I’ve never heard of any surname being mentioned. Anyway, Sir Rafael discovered the dalliance between Lady Pamela and this young Boris. He had been drinking heavily all day, as was his wont, and he now fell into a drunken rage. The terrified footman sought refuge in the cellar of the house. Sir Rafael raged around the house waving a cavalry sword and searching for young Boris. Now this sword, or so they say, was a razor sharp sabre, so Boris did well to keep out of the way. But eventually Sir Rafael made his way down to the cellar, and there he found Boris.’

‘And this is where the murder comes in?’ said Warnie, taking up another slice of hot buttered toast and spooning on marmalade as if the world was about to run out of the stuff and he had to get his share while he could.

‘Exactly, sir. With Lady Pamela standing on the stairs and screaming for him to stop, Sir Rafael butchered poor Boris with that wickedly sharp sabre. Then seeing the dead body lying there in front of him seemed to sober him up. He realised what he’d done, and the consequences he’d face if caught. He forced his wife, trembling and sobbing with fear, to help him dig a hole in the cellar floor and bury the body.’