The Essential Edgar Cayce (5 page)

Read The Essential Edgar Cayce Online

Authors: Mark Thurston

Tags: #Body, #Occultism, #Precognition, #General, #Mind & Spirit, #Literary Criticism, #Mysticism, #Biography & Autobiography, #Telepathy), #Prophecy, #Parapsychology, #Religious, #ESP (Clairvoyance

In order to see our personal role in evil, it’s useful to return to the first point that there are many faces of evil and that some of these faces are more alive in us personally than others. According to Cayce, there are at least five

angles

from which we can understand and relate to evil (or

bad,

as he sometimes referred to it):

A lack of awareness.

Sometimes evil can be understood as a deficit in conscious awareness, a state of being “asleep” spiritually. Evil constantly tugs at us to become less and less conscious, more and more distracted. Temptation surrounds us daily.

Extremism.

As noted earlier, Cayce sometimes liked to remind seekers that Christ Consciousness is the meeting point between two extremes—that is, the middle path. Therefore, one face of evil involves embracing an extreme point of view, even denying the validity of any counterbalancing view, and surely our world is full of such extremists right now. What’s a little harder to see is our

own

tendency to go to extremes. For example, we may be tempted to embrace

other-worldliness

in the extreme in an attempt to have a more spiritual life and in the process lose connection with and appreciation of the practical aspects of material life. But just as likely, we might be tempted to go the other way and become so pragmatically down-to-earth that we ignore the invisible side of life. Either approach is a kind of evil. Christ Consciousness creates a meeting ground for the two extremes, creating a life that integrates the mystical with the mundane.

Aggression and invasion.

We think of these terms in connection with warfare, but all human relations have the potential for these forms of evil. We try to subvert the free will of others by overpowering them with our own will. One gift of authentic practical spirituality is the capacity to stand up for oneself (and one’s ideals) with integrity but without becoming aggressive and invasive in the process.

Transformation.

Here is a particularly hopeful way of viewing evil. Evil is something that just falls short of the mark, just misses it. “How far, then, is ungodliness from godliness? Just under, that’s all!” (254-68). That doesn’t mean ignore the fact that evil falls short; it means stay engaged with anything ungodly and keep working to transform it. Sometimes, only a mere readjustment is required.

For example, an individual might have a destructive tendency to manipulate others, but that trait may be just short of something that is constructive and healthy. While he may have a talent for motivating people, that talent has become distorted or is being misused in such a way that it qualifies as manipulation. Instead of rejecting that manipulative trait, he can uplift and transform it into its full potential. If he only tries to suppress the fault, he will miss out on a valuable side of himself.

Rebellion and willfulness.

This is Edgar Cayce’s most fundamental idea about evil. We are given the choice daily between good and evil. Perhaps what tips the scale toward evil is

rebellious willfulness,

as Gerald May refers to it in his 1987 book

Will and Spirit.

“Evil seeks to mislead or fool one into substituting willfulness for willingness, mastery for surrender.”

And so the choices are always ours in the big and little decisions we make each day in response to evil. As concerned as we must be about evil on the national and international scale, an essential principle Cayce challenges us to look at is our own relationship to these very themes.

12. Learn to stand up for yourself; learn to say no when it’s needed.

Life-affirmation is great, but sometimes we must learn to say no before we can say yes. Hearing this may give us pause, fearing that we’re about to go down a path to negativity. Do we really want to honor

negation

in this way? But, in fact, a higher degree of mental health is required to set boundaries and define ourselves with a no.

Consider Cayce’s bold advice: “So live each and every day that you may look any man in the face and tell him to go to hell!” (1739-6). People usually laugh nervously when they first hear this passage. Surely this is not Edgar Cayce, the life-affirming spiritual counselor, saying something like this! Perhaps it’s just another example of his wry humor. But Cayce was dead serious about the need for us to define and defend our boundaries vigorously, and sometimes that means telling someone to go to hell. More often, it’s enough to just firmly say no, letting it be known who you are and how you need to be treated.

It’s all a matter of affirming one’s personhood. Beneath the negation there is actually a more significant

affirmation

of something. The point is this:

There is no love and no intimacy with others unless we can first define our own boundaries.

Saying no is a matter of the most basic practical spirituality. Then, from that position of relative strength, we can enter into relationship with another individual. As strange as it may sound, loving someone may start by stepping back, saying no, defining oneself, and

then

reaching out and building an authentic bridge to that person.

This sounds a lot like

self-assertion,

as popularized in modern psychological practice and as Edgar Cayce himself sometimes advocated. One good example was advice given to a thirty-four-year-old machinist foreman who suffered from the social illness of letting other people take advantage of him. Cayce’s blunt advice: “The entity because of his indecisions at times allows others to take advantage of him. The entity must learn to be self-assertive; not egotistical but self-assertive—from a knowledge of the relationship of self with the material world” (3018-1).

Another example is Cayce’s repeated admonition of just how important it is to be able to get angry. Anger is an emotion directly related to saying no. Of course, he isn’t saying we need to run around blowing our stacks every day, but he

did

emphasize the need to express anger in the

right

way. “Be angry but sin not. For he that never is angry is worth little” (1156-1). But then Cayce adds how important it is to have a

container

for that anger. “But he that is angry and controlleth it not is worthless.” Note here that control does not mean “suppression” but “proper direction.” It’s a crucial distinction.

THE MODELS AND STRUCTURES OF THE CAYCE PHILOSOPHY

With the twelve essential themes of Edgar Cayce’s philosophy in mind, we’re still left wondering how it all fits together. What are the structures and universal laws of life that integrate these dozen principles? Over the years, Cayce proposed several different

formulas

and

models

in his readings. Taken together, they create a comprehensive

map

of how life works for a

spiritual

being who is experiencing

materiality.

1. Links among body, mind, and spirit.

The holistic philosophy presented by Edgar Cayce emphasized the interconnections of the physical, the mental, and the spiritual. Often he offered a formula showing the sequence of how material reality (including physical health or the lack of it) comes into being: “The spirit is the life, mind is the builder, and the physical is the result.”

The spirit is the life

means that there is just one fundamental energy of the universe. It is the life-force, and it is fundamentally a spiritual, nonmaterial vitality. It can, however, manifest itself in the material world.

Mind is the builder

means that with the mind each of us is able to give that one spiritual life-force a

vibration

or a pattern. We create with the mind. Thoughts are things, so to speak, although the reality of a

thought-form,

as Cayce sometimes called it, is not immediately apparent to our physical senses.

The physical is the result

means that all we perceive as material reality is an expression in the physical world of what was previously mental. Our life circumstances, and even the condition of our physical bodies, are shaped by our attitudes and emotions.

One analogy that Cayce proposes is that of a movie projector. The projector’s lightbulb is like the spiritual life-force; the images on the film are like the mental creations of our thoughts and feelings; and the image projected upon the screen is analogous to what we experience as our physical reality.

All of this emphasizes the

creative

element within us. We create our own reality in the world; we create our own future. The arts—painting, music, dance, etc.—are profound ways to bridge the apparent gap between the spiritual and the material. So emphatic was Cayce about the significance of this creative principle that a frequent synonym he invoked for God was

the Creative Forces.

2. Links among ideals, free will, and soul growth.

A second formula from Edgar Cayce’s philosophy is not stated explicitly in the readings but can be gleaned form the spiritual advice he gave to hundreds of people. There are three factors involved in this formula, and they flow out of the relationship among the three: ideals, free will, and the development of our potential as souls. In the formula, they are presented in sequence: “Envision an ideal, awaken and apply the will, and soul growth will be the result.”

We noted earlier that one essential theme in Cayce’s philosophy is that “changing anything starts with an ideal.” And here that theme is expanded upon and linked to other essential principles. One explication has the ideal as something we

envision

rather than figure out logically—“it comes and find us,” so to speak. Our task is to be open and attentive, ready to notice and reaffirm what arises spontaneously from the soul. In fact, if one’s ideal is merely something that has been figured out logically, then probably its potency and impact is limited to the material world of cause and effect where logic reigns supreme. An ideal that is truly life-transforming must come from a deeper place within ourselves. It is something we intuit as it reveals itself to us. Envisioning an ideal is the

recognition and affirmation of something that calls to us from our own depths.

Once the ideal has been discovered, we have to do something with it. That requires the use of the free will, which is the hallmark of our individuality. But the free will tends to be asleep inside us; we cruise through life on automatic pilot just reacting to things that trigger us. For the ideal to make a difference in our lives, the free will has to be awakened and then applied.

Applying the ideal is at the heart of what Cayce calls

soul-growth.

No authentic transformation of the soul can take place unless guided by the ideal. And, just as important, the essence of developing the soul is allowing for the free will to emerge.

3. Three levels of the mind.

One way to understand the human mind is to see it as three levels, or layers, that interact and influence one another. Edgar Cayce calls these layers the

conscious mind,

the

subconscious mind,

and the

superconscious mind.

Because the subconscious and the superconscious tend to be outside our immediate awareness, together, they make up what is widely termed

the unconscious.

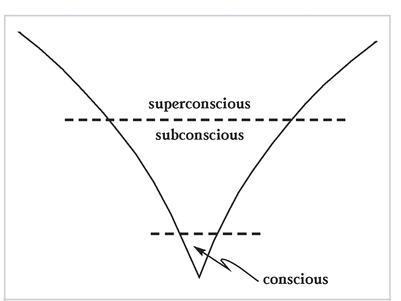

While Cayce was not alone in proposing this three-layer scheme, or the first to employ these terms, his image of the relationship between the layers is special. Many schools of psychology suggest that the higher mind (or superconscious) is like the attic of a house, the lower mind (subconscious), as the storehouse of all memory, is like the basement, and the mind of everyday awareness (conscious) is in between, the main floor of the house. Cayce felt such a scheme was misleading. Relative to the conscious mind, the subconscious and superconscious are not in different directions, so to speak; rather, we must pass through our subconscious memories in order to make a connection with the unlimited potential of our superconscious.

The three-layer model shown in Figure 1 on page 36, therefore, is different than a three-story house. It’s based on a dream that Cayce had in 1932: “There was a center or spot from which, on going into the state, I would radiate upward. It began as a spiral, except there were rings all round—commencing very small, and as they went on up they got bigger and bigger.” He offered an interpretation of his dream in a reading (294-131), indicating how, when giving a reading, he was able to elevate his consciousness (which he likened to a

dot

or

tiny speck

), through the subconscious, and on into the superconscious (or what he termed

the heavens

). As he put it, “[A] tiny speck, as it were, a mere grain of sand; yet when raised in the atmosphere or realm of the spiritual forces it becomes all inclusive, as is seen by the size of the funnel—which reaches not downward, nor outward, nor over, but direct to that which is felt by the experience of man as into the heavens itself.” Herbert Puryear, a clinical psychologist, drew the V-shaped diagram shown in Figure 1 to illustrate Cayce’s interpretation of his own dream.

Cayce’s model has significant implications for how we understand our spiritual quest. As we strive to make a connection with the higher self—or

the divine

—then we should expect to encounter our own subconscious “stuff ”—our unconscious desires, fears, resentments. Quite simply, it means that our quest to connect with the superconscious very likely will involve a profound encounter with ourselves, including those aspects we are ashamed or afraid of—our

shadow,

to use a term from Jungian psychology. And although Edgar Cayce was not conversant in the ideas of Carl Jung, his picture of the human mind bears a strong resemblance.