The Dead Boys (6 page)

“No. It just seems weird.”

“It's common, really.” Hank yawned, flipping his stringy hair out of his eyes. “Over time, they get into everything.”

“Why?”

“Looking for water, usually. In the desert those roots will get into sewers, plumbing, even crawl all the way to the river. Can't believe this one went after the air conditioner, though. Must be desperate.”

Hank rummaged in his pocket, pulled out a pocket knife, and began to clean his fingernails. He turned his narrow green eyes on Teddy. “You know, you look familiar, kid,” he said as he rubbed an old scar on his forehead. “Do I know you?”

“I don't think so,” Teddy said. “I just moved here.”

Hank shrugged and snatched the new pipe from Teddy. He plopped back down to install it, hoisting his rump back up in the air.

Teddy stared at the old mutilated pipe. “This is completely destroyed.”

“Yeah,” Hank agreed from under the air-conditioning unit. “They pry their way in. Powerful things, though they usually just crack stuff. That little number looks like a nuclear bomb went off in it.”

Hank finished attaching the new pipe and scooted out from under the air conditioner, wiping his hands on his shirt.

Teddy nodded, troubled by how easily simple tree roots had forced him out of his home.

“Will they come back?” he asked.

Hank shrugged. “Maybe, eventually. No one can give guarantees, kid.”

CHAPTER 9

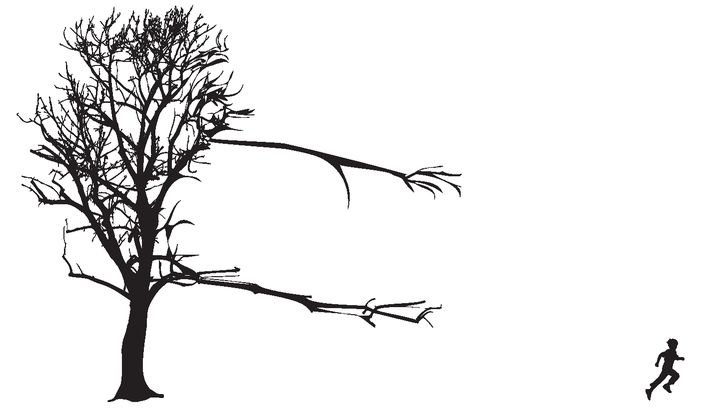

Once Hank left, Teddy retreated inside the house. But he knew deep down he couldn't simply cower in his home. If the tree was trying to get in through the window and sabotaging the air conditioner to force him outside, he had to figure out why.

Summoning his courageâit was just a tree, after allâTeddy pushed the kitchen door open and peeked outside. He crept to the edge of his backyard, where the massive sycamore rose above him on the other side of the fence, its cracked wood riddled with scars from the many decades of nature's abuse. It seemed to frown down at him, healthy but somehow unsatisfied.

“What do you want?” Teddy asked.

The sycamore, of course, did not reply. It only swayed in the hot desert breeze, and Teddy instantly felt stupid for talking to it. He turned to go back inside.

Just then, something hit Teddy in the head.

“Oww,” he grumbled as a sycamore seed ball bounced to the ground beside him. It was the size of a golf ball, and its surface bristled with pointy seeds. Teddy looked up to see where the ball had dropped from and saw a boy sitting on a branch above him almost completely hidden by leaves.

“Hey, what's cookin'?” the boy said. His grin was not quite a smirk, so Teddy couldn't decide if he'd meant to throw the sycamore ball hard enough to hurt him or just to get Teddy's attention.

The kid was about Teddy's age, but looked a little taller, and he wore long wool knickers and an argyle patterned sweater-vest over a white shirt. His outfit made him look like an old-time schoolboy dressed for fall instead of summer.

“Why'd you do that?” Teddy said, rubbing his head where he'd been struck by the sycamore ball.

“I didn't,” the boy replied. “The tree dropped it.”

“It's a pretty odd coincidence,” Teddy said, “seeing as you were sitting

directly

above me when it fell straight down and hit me

directly

in the middle of the head.”

directly

above me when it fell straight down and hit me

directly

in the middle of the head.”

“A wiseacre, eh?” the boy said. “I like that.”

Before Teddy could reply, he heard a long, low groan, like the creaking timbers of a massive wooden ship. He whirled around to find the source, but it seemed to come from all around him, even up from the ground.

“Are you making that sound?” he asked.

The kid chuckled. “Do I look like I could make a sound that grand?”

As Teddy stood trying to figure out what might make such a

grand

sound, he spotted a large branch above his head swaying in the breeze. Only it wasn't just moving back and forthâit was also moving down toward him, creaking and groaning as it came. The branch descended to within arm's reach of Teddy and stopped directly in front of him.

grand

sound, he spotted a large branch above his head swaying in the breeze. Only it wasn't just moving back and forthâit was also moving down toward him, creaking and groaning as it came. The branch descended to within arm's reach of Teddy and stopped directly in front of him.

Teddy leaped back. “Did you see that?” he gasped. “That branch just moved!”

The kid nodded and slid from his own branch onto the base of the moving branch, perching himself so that his legs dangled over the side. “Sure. The wind blows. They make noise. They go up. They come down. They move side to side. It's no big deal.”

Teddy eyed the tree suspiciously, unconvinced that it was just the wind.

“Swell, huh?” the boy said. “It's the biggest tree on the block.” He waved a foot toward the smaller birch, willow, and fruit trees lining the long street.

“You live near here?”

“Yeah,” Teddy said. “I just moved in next door.”

“I'm Eugene,” the boy announced, “but everyone just calls me Sloot. I'm pretty much in charge around here, because I've been here the longest.”

Teddy had a sudden brainstorm. “Hey, since you've lived here so long, do you know Walter or Albert?”

“Of course,” Sloot said.

“Really?” Teddy asked, excited and a little surprised that someone finally knew what he was talking about. “I just met them, but they both kind of disappeared.”

“Nonsense,” Sloot said. “I saw them this morning.”

CHAPTER 10

Teddy let out a deep breath as relief washed over him. Somehow Walter hadn't been buried and Albert had gotten away.

“That's so great . . . !” he exclaimed, the words pouring out of him now. “Whoa. You wouldn't believe what I thought happened to them. I mean, Walter must have totally fooled me, because it seemed so real when heâ”

“They're fine!” Sloot interrupted angrily. “Walter's as weird as ever, and Albert's still a lard-butt. Do we really need to blather on about them?”

“Uh, no, I guess not,” Teddy mumbled, taken aback by Sloot's change in tone.

“So, do you like this place?” Sloot asked quickly, changing the subject.

“No offense, but I think it's a little weird.”

Sloot laughed. “Boy howdy, you got that right. The G-men built this town from nuthin' right up out of the desert a few years ago.”

“G-men?”

“Government men. Do your folks work at the nuke-u-lar project? You can tell me. I'll keep it under my hat.”

“My mom does, yeah,” Teddy said. “But I don't think it's a secret.”

Sloot shrugged. “Well, loose lips sink ships, as they say. My dad works there too, but if he knew I said something about it he'd give me a knuckle sandwich, so don't

you

go tellin' anybody.” Sloot made a fist and gave Teddy a sudden fierce look.

you

go tellin' anybody.” Sloot made a fist and gave Teddy a sudden fierce look.

“Ooo-kay,” Teddy said carefully.

Sloot nodded, satisfied. “You coming up?” he said, instantly turning cheery again.

Teddy eyed the huge tree. It looked like a long way up, and Sloot's sudden changes in mood made him nervous. “Wasn't planning to.”

“Aww, c'mon,” Sloot cooed. “If you take a gander from the top, you can see all the way to the river. Branches are thin up there, but they might hold you. You're nice and skinny.”

“Sounds like a good way to get killed.”

Sloot went quiet for a moment. “Pretty good, yeah,” he finally said. “A fella could climb up there, and nobody would find him . . . ever.” Then he looked over his shoulder toward the trunk of the tree and the A-house beyond. “Well, my time's about done. You coming up or not?”

“Uh, I think

not

.”

not

.”

Sloot frowned, his face turning dark again with a flash of anger. “I'm not sure I heard you right. Did you tell me no?”

“Uh, well, yes,” Teddy spluttered. “I mean, yes, I said no.”

Sloot rolled his eyes. “Well, I can't sit around flappin' my lips all day with some meatball like you who can't make up his mind.”

“But I

did

make up my mind.”

did

make up my mind.”

Sloot stood up on the branch. He gave Teddy a long look. “No, you haven't.” He stepped out to the middle of the branch, which swayed upward in the breeze, lifting him into the tree as if it were a small elevator.

Teddy stared up at the tree. His instinct, common sense, and rattled nerves all told him to walk away and forget about Sloot. But instead, the longer he gazed into the sycamore, the more he felt it drawing him closerâthe same way the A-house had pulled him to it the day he'd arrived.

He marveled at how it could be so unnaturally green, its leaves so strangely vibrant and healthy compared to the dead yard. The tree was so full of life that it felt inviting. More and more, Teddy found that he

did

want to climb up into it. He wanted to see Richland from the top.

did

want to climb up into it. He wanted to see Richland from the top.

Maybe just halfway to start with,

he thought.

What would be the harm?

he thought.

What would be the harm?

Like a moth attracted to a bright light, Teddy found himself walking toward the trunk of the tree. The large branch creaked in the breeze, lowering itself again.

They go up, they come down . . . no big deal

, Sloot had assured him.

, Sloot had assured him.

Teddy climbed onto the branch, and it immediately lifted him into the tree. In an instant, he was ten feet off the ground, climbing through the limbs.

As he moved higher, the soft leaves brushed his arms and caressed his face. Branches seemed to bend toward him so he could reach them easily and keep climbing up. The air felt cooler as he rose in the protective shade of the tree, and because he couldn't see more than five feet in any direction, the outside world soon seemed miles away.

“Sloot?” he called.

“Up here,” Sloot's faint voice replied.

He still couldn't see Sloot, so he kept working his way higher. Somehow, the climb didn't seem dangerous. The branches felt solid beneath his feet. In fact, it was so easy that it felt almost as though the branches were passing him up from one to the next.

“Up where?” He called.

“Keep coming.” Sloot's words sounded muffled, like he had leaves in his mouth.

“Show me where you are,” Teddy said, wondering if Sloot was kidding around, perhaps lurking somewhere nearby to jump out at him or smack him with another sycamore ball.

As Teddy spoke, the branches above him parted, revealing a huge, gaping knothole in the trunk of the tree. The hole was more than three feet across and rimmed with a thick, swollen band of purplish bark that glistened like the wet lips of a fish. There sat Sloot with his rump in the hole and his upper body and legs hanging out so that he looked folded in the middle.

“You're almost here,” he said eagerly.

“This is getting a little high for me,” Teddy replied from below. “I just wanted to see the view.”

“Sure. Relax. You're high enough now for a look around.” Sloot pointed out through the thick branches, and the hot breeze eased them apart.

Suddenly, Teddy could see for miles. He immediately spotted the scrubby park by the river to the east where he'd met Albert. But when he looked north, Walter's construction site was missing. In fact, while he didn't know the neighborhood well yet, there were a lot fewer rooftops than he expected. And there were no homes at all where he thought Lynwood Court should beâonly open desert.

“It looks a lot smaller,” Teddy said.

“It used to be,” Sloot said from above him. “Okay, you've seen enough, and I'm about out of time here. Come on up. I want to show you something.”

The branches on the tree shifted again, obscuring Teddy's view of the town. Inside the thick limbs, it once again grew shady, almost dark. The leaves were still touching Teddy as they had on the way up, but now they felt probing instead of caressing. He felt one inch behind his ear and another slither up his sleeve into his armpit, where their strangely wet surfaces stuck to his skin, and they clung like leeches.

Other books

Heat Rising: A KinKaid Wolf Pack Story by Lee, Jessica

Our Story: Aboriginal Voices on Canada's Past by Tantoo Cardinal

The Phenomenals: A Tangle of Traitors by F. E. Higgins

The Soulstoy Inheritance by Jane Washington

Night of Cake & Puppets by Laini Taylor

Band of Acadians by John Skelton

Arthur & George by Julian Barnes

Death be Not Proud by C F Dunn

A Place to Call Home by Christina James