The Dead Boys (5 page)

Walter grinned again. “Oh, yeah? I'll bet I can set fires faster than you can put them out.”

With that, he romped off through the half-built house, thrusting the torch out at random and singeing the two-by-four framing and plywood floors as he went. In his wake, he left charred black marks, a burnt smell, and bursts of laughter.

Feeling a strange mix of exhilaration and guilt, Teddy followed, trying to keep up. Mostly the flames didn't catch, but once Teddy had to stop and stomp out a newspaper that was starting to send up tendrils of smoke.

When he had made a full circuit through the house, Walter darted between the two-by-four framing and leaped from the second floor down into a huge pile of dirt on the ground. He ran to the next unfinished house to resume his scorching.

Teddy hustled down the stairs behind him, his excitement fading as Walter showed no signs of stopping. He ran to the next house, desperately following the trail of smoldering wood and black scars his new friend had left behind.

“Walter! You've gotta stop!” he yelled.

When he entered the next unfinished home, Teddy found the discarded torch on the floor. But Walter himself had disappeared out the other side and was nowhere to be seen.

Then he heard Walter's voice. “Down here, slowpoke!”

Teddy walked to the edge of the sewer trench between the building sites and spotted Walter standing at the bottom, ten feet down.

“Fun stuff, huh?” Walter said again.

“No,” Teddy said. “I don't think setting fires is fun. We should get out of here before the workmen come back.”

“Looky here.” Walter picked up a shovel and smacked the dirt-and-rock wall of the trench. A small section of wall caved in, and he leaped aside as it scattered rocks across his feet.

“Dare ya,” Walter said.

“Dare me what?”

“Dare ya to make a bigger avalanche.”

“I don't think so,” Teddy said.

“What, no guts?” Walter snorted. He raised the shovel again. “Scaredy cat?”

“I wouldn't keep doing that,” Teddy warned.

“No.

You

wouldn't.”

You

wouldn't.”

With a smirk, Walter swung the shovel at the wall right below Teddy's feet. A refrigerator-sized chunk of earth broke away, and Teddy leaped back as the bank caved in beneath his shoes.

Below, Walter dodged the tumbling debris, diving along the bottom of the trench as rocks and dirt fell behind him. Once it stopped, he stood up, laughing hysterically.

“That was awesome!” he cried. “C'mon down and try it.”

From the edge of the trench, Teddy surveyed the wide, crescent-shaped scar Walter had made in the dirt. Exposed rocks and the crooked ends of still-quivering tree roots jutted out.

“No way,” Teddy said, looking over his shoulder for his bicycle. It suddenly seemed like a good time to say good-bye to Walter.

“Please,” Walter said in a suddenly serious tone. “This is my last chance.”

Teddy wasn't sure exactly what Walter meant, but shook his headâthere was no way he was going down there. At that moment, the wall of the trench suddenly shifted. The tree roots sticking out of the wall jerked and twitched, knocking small stones loose, and a long crack began to snake through the dirt near Teddy's feet at the edge of the pit.

“Run!” Teddy yelled as Walter watched the crack widen above him.

Walter didn't run. He stood in place with a resigned look on his face and reached up, pleading. “Help me, Teddy. Grab my hand.”

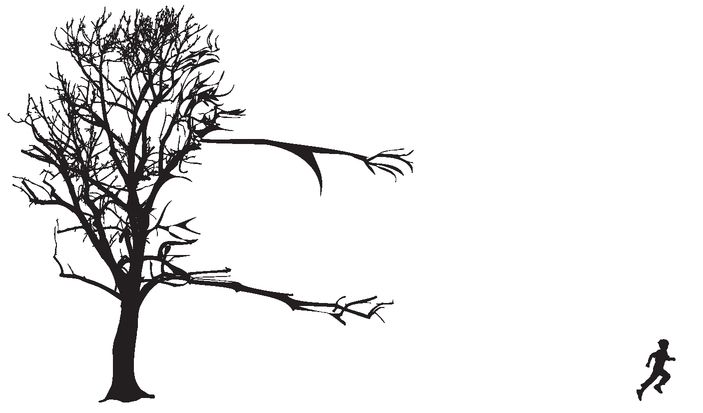

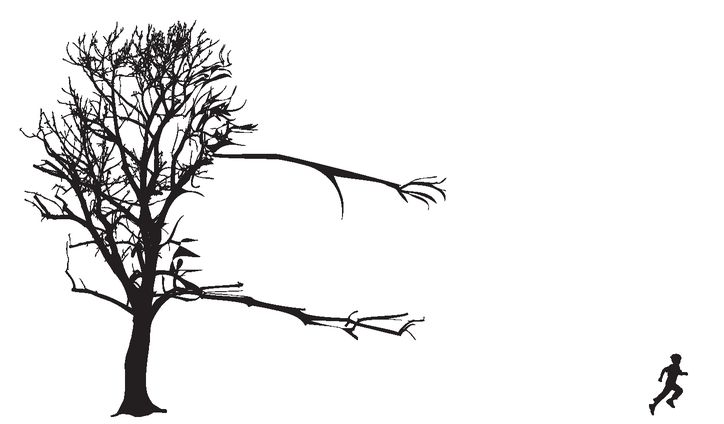

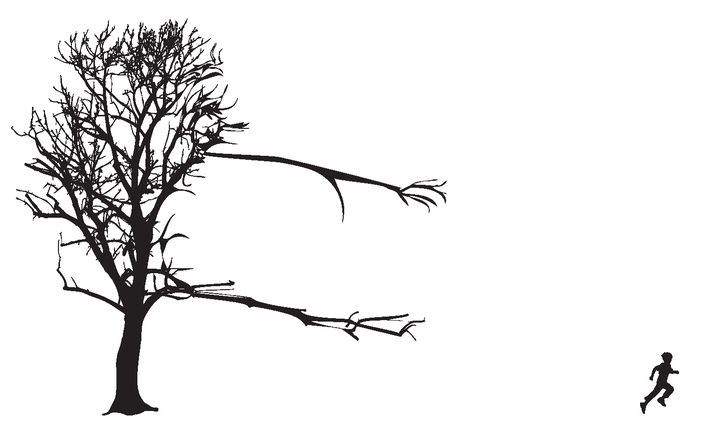

But Teddy wasn't listening anymore. Instead, he stared in horror as the gnarled, handlike tree roots writhed forth from the wall of the trench and grabbed Walter's ankles and arms, holding him in place. Then the wall collapsed, covering his new friend with ten feet of dirt and rock.

CHAPTER 6

A wailing patrol car banked hard onto Saint Street. Teddy waved from the sidewalk in front of the house at 550 Saintâa half block from the construction siteâwhere he'd run to call the police.

The car screeched to a stop. “Where's the buried kid?” a police officer shouted out the window.

“Down there in Lynwood Court!” Teddy yelled back. The car lurched forward and disappeared around the corner. Teddy hopped on his bike and followed it down the street.

When he arrived at the cul-de-sac, the officer was pacing beside his car in front of a series of completely finished homes with lawns, welcome mats, and cars in their drive-ways. The Lynwood Court sign was in the same place, but it was faded, not shiny and new. And there were no construction sites.

Teddy wheeled his bike up a driveway and kicked a garage door that hadn't been there before in disbelief. It was real.

“Calm down there, son,” the officer said. His blue uniform read BARNES across the pocket.

“But it was here,” Teddy said.

“What was here?” Officer Barnes asked.

“Lynwood Court.”

“This

is

Lynwood Court.”

is

Lynwood Court.”

An ambulance squealed to a stop behind the patrol car, and Teddy began to feel the need to explain something he didn't understand.

“Yeah, I know,” he said. “But the houses were under construction before.”

“Before what?”

“Before I called.”

“Young man,” Officer Barnes said, “Lynwood Court was under construction forty years ago.”

A fire truck pulled up now too, its crew leaping out to assist with the horrible emergency Teddy had reported. As Teddy watched them, shifting from foot to foot and wishing he were somewhere else, he began to feel sick to his stomach. The homes in the cul-de-sac before him

did

look forty years old.

did

look forty years old.

Paramedics and firemen joined Teddy and Officer Barnes on the sidewalk, huffing from their mad dash to the scene with their heavy equipment.

“Where's the trench?” one of the firemen asked.

Teddy shrugged. “It was between the houses around here somewhere, but now it's all lawn.”

Officer Barnes harrumphed. “Okay, so you saw a boy buried in a trench that you can't find now. What was his name?”

“Walter.”

“Walter what?”

Teddy sighed. “I don't know.”

“I see. So a boy you don't know disappeared in a hole you can't find.” Barnes shook his head and waved the emergency crews away. He opened a notebook and took out a pen. “And what's your name, son?” he grumbled.

Teddy's shoulders slumped. He dropped his head onto his chest; he couldn't look Barnes in the eye anymore. “Teddy,” he said.

CHAPTER 7

Once the emergency crews had cleared out, Officer Barnes drove Teddy home. He was reluctant to leave Teddy stranded outside his house without a parent, and it took Teddy a long time to explain that he didn't know the location of his mother's new high-security job and that her phone number was locked inside the house. He also declined Barnes's offer to break in for him, and, finally, Barnes had simply left with his name and home phone number so that he could call Teddy's mom later, probably to tell her how much trouble Teddy had gotten himself into by telling such a ferocious lie.

Teddy was still outside on the porch when his mother pulled up after work to find him sitting there sunburned as red as a lobster. He didn't tell her about Walterâhe wasn't exactly sure what

to

tell her. Instead, he simply said that the air conditioner had broken, he'd taken the check over to Lynwood Court, then he'd hung out in front of the house, all of which were true.

to

tell her. Instead, he simply said that the air conditioner had broken, he'd taken the check over to Lynwood Court, then he'd hung out in front of the house, all of which were true.

If I'm lucky,

he thought,

Officer Barnes will get busy and forget about me.

he thought,

Officer Barnes will get busy and forget about me.

His mom made spaghetti for dinner, and Teddy silently plowed through two full plates to make up for missing lunch. As he ate, he listened to her talk about her new job at the nuclear plant.

“I like the lab here,” she was saying, “and I'll get a raise after my probationary period. Until then, we'll have to watch our budget. Thank goodness you're responsible enough that I can leave you home withoutâ”

“Can nuclear waste make people hallucinate?” Teddy interrupted.

“Well, no,” she answered, seeming surprised about his concern with toxic waste, “although it

can

be dangerous.”

can

be dangerous.”

“How?”

She thought for a moment. “Some highly radioactive material gives off energy in large, lethal dosesâit kills things. Low-level material takes a longer time to decay, but the energy still seeps out, and it can mutate living cells. They're very careful with it nowadays, though.”

“How long does it take to decay?”

“Why do you ask?”

“Just interested in your new job,” Teddy fibbed.

“It varies,” she answered. “It has what they call a half-life. Half the energy of something radioactive is drained over a period of time. It takes that same amount of time again to drain half of what's left, and so on. The energy dwindles until there's almost nothing left.” She paused to take a mouthful of spaghetti. “But don't worry,” she reassured him. “I work in a very safe area at the plant.”

Teddy nodded that he understood. But it wasn't an area at the plant he was worried about.

CHAPTER 8

The next morning, Teddy sat at the kitchen table as his mom got ready for work. He'd lain awake puzzling over the disappearances of Walter and Albert, all the while listening to the branches clawing at his bedroom window. Either the boys in the neighborhood were playing very disturbing tricks on him or his mind was, but he couldn't figure out which, and for the second night in a row, he hadn't slept a wink.

His mom noticed. “So I take it you haven't had the best first couple of days here,” she said.

“Not the best, no,” Teddy admitted.

She rose from the table. “I'm too new to ask for time off work or I'd stay here with you, but listen, I want you to stick close to home today, okay?”

“No problem,” Teddy mumbled, and he meant it. He wasn't going near rivers, construction sites, or anyplace remotely dangerous.

“Okay,” his mom said, giving him a good-bye kiss for which he felt too old. “A repairman is coming later to look at the air conditioner.”

An hour later, the repairman was bent under the air-conditioning unit with his skinny rump in the air. Teddy stood nearby holding a length of new pipe.

The repairman tossed out a piece of old metal pipe from the unit that was tattered and mushroomed out at one end as though it had exploded.

“Here's your problem,“ he said. “Tree roots in your pipes.”

“What?”

The man stood up, one greasy hand on his pockmarked chin. The name tag on his coveralls said HANK.

“You deaf?” he said.

Other books

Fade Away (1996) by Coben, Harlan - Myron 03

Take Me, Cowboy by Maisey Yates

The Chaos Curse by R. A. Salvatore

Living Rough by Cristy Watson

Bound to the Alpha: Part One by Rivard, Viola

The Apple Tart of Hope by Sarah Moore Fitzgerald

Billionaire Matchmaker: Complete Series (Contemporary Romance) by Baxter, Cordelia

Rebel's Tag by K. L. Denman

Laying Down the Paw by Diane Kelly

Touching Silver by Jamie Craig