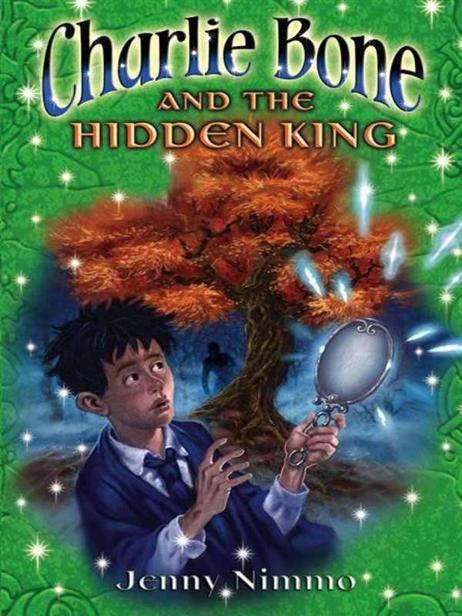

Charlie Bone and the Hidden King (Children of the Red King, Book 5)

Read Charlie Bone and the Hidden King (Children of the Red King, Book 5) Online

Authors: Jenny Nimmo

Charlie Bone and the Hidden King

(The Children of the Red King, Book 5)

Jenny Nimmo

Contents

THE CHILDREN OF THE RED KING, WILED THE ENDOWED

THE ENDOWED ARE ALL DESCENDED FROM THE TEN CHILDREN OF THE RED KING.

MANFRED BLOOR. Teaching assistant at Bloor's Academy A hypnotist. He is descended from Borlath, elder son of the Red King. Borlath was a brutal and sadistic tyrant.

NAREN BLOOR. Adopted daughter of Bartholomew Bloor. Naren can send shadow words over great distances. She is descended from the Red King's grandson who was abducted by pirates and taken to China.

CHARLIE BONE. Charlie can travel into photographs and pictures. Through his father, he is descended from the Red King and through his mother, from Mathonwy a Welsh magician and friend of the Red King.

IDITH AND INEZ BRANKO. Telekinetic twins, distantly related to Zelda Dobinski, who has left Bloor's Academy.

DORCAS LOOM. An endowed girl whose gift is the ability to bewitch clothes.

UNA ONIMOUS. Mr. Onimous's niece. Una is five years old and her endowment is being kept secret until it has fully developed.

ASA PIKE. A were-beast. He is descended from a tribe who lived in the northern forests and kept strange beasts. Asa can change shape at dusk.

BILLY RAVEN. Billy can communicate with animals. One of his ancestors conversed with ravens that sat on a gallows where dead men hung. For this talent he was banished from his village.

LYSANDER SAGE. Descended from an African wise man, Lysander can call up his spirit ancestors.

GABRIEL SILK. Gabriel can feel scenes and emotions through the clothes of others. He comes from a line of psychics.

JOSHUA TILPIN. Joshua's endowment is magnetism. His origins are, at present, a mystery: Even the Bloors are unsure where he lives. He arrived at their door alone and introduced himself. His tuition is paid through a private bank.

EMMA TOLLY. Emma can fly Her surname derives from the Spanish swordsman from Toledo whose daughter married the Red King. The swordsman is therefore an ancestor of all the endowed children.

TANCRED TORSSON A storm-bringer His Scandinavian ancestor was named after the thunder god, Thor. Tancred can bring wind, thunder, and lightning.

OLIVIA VERTIGO Descended from Guanhamara, who fled the Red King's castle and married an Italian prince. Olivia is an illusionist. The Bloors are unaware of her endowment.

PROLOGUE

The Red King and his friend walked together through the forest. It was a golden autumn and leaves fell about them like bright coins. The king was tall, his black hair showed not a trace of gray and his dark skin was unlined, but the sorrow in his eyes was centuries old.

Mathonwy, the magician, was a slighter man. His hair and beard were silver-white and his back bent from years spent in the forest. He wore a cloak of midnight blue patterned with faded stars.

Ten paces behind the men came three leopards; they were old now and not so quick as they had once been, but their gaze never wandered from the figure of the king. He was their master and their friend and they would have followed him through fire.

Mathonwy was troubled. He knew that this was not one of those companionable walks that he was used to taking with the king. Today their pacing had a deeper purpose. Each step took them farther from the world of men, and closer to the forest's heart.

They came, at last, to a glade where even the dead leaves were silent. The grass was the color of honey and the hawthorn trees were heavy with crimson berries. Mathonwy rested on a fallen tree but the king stood looking up through the bare branches. The sky had turned a burning red, but in a high band of deepest blue, the first star showed.

"Let us make a fire," said the king.

Mathonwy delighted in bonfires. He sang in Welsh while he gathered the kindling, and the merry song hid the dread in his heart. The dead twigs were tinder dry and soon they had a small blaze going. A thin column of smoke lifted through the trees and the king declared it to be the sweetest scent in all the world.

Now,

thought Mathonwy.

Now, he is going to ask me.

But it was not yet.

"First the cats," said the king. "They cannot survive for much longer in a land of cold winters and callous hunters. Come here, my good creatures."

The leopards walked up to the king. They purred as they brushed their heads against his hand.

"It is time for you to wear new coats," the king told them. "Find a master who is good, for this one has to leave you now."

It was said. Mathonwy shuddered. The king was leaving. How empty the forest would be without the companion who had filled his mind with wonders, who had shared his thoughts, answered his doubts, conversed from sunrise to moonset.

The king walked around the fire with long, measured strides and the leopards followed him, around and around and around.

"Watch my children," the king commanded them. "Seek out the descendants of the children who are lost to me; sons and daughters of brave Amadis and bright Petrello, children of gentle Guanhamara and clever Tolemeo, descendants of my youngest child, Amoret. Help them, my loyal cats, keep them safe."

When the king stepped away from the fire, the big cats continued to circle it. They were running now, leaping and bounding.

The king raised his arm. "Bright flame, burning sun, and golden star," he chanted. "Guard my children with your wild hearts. Live safely in the world of men, but remain forever what you are."

Mathonwy had seen such spells as these before, but tonight the king's magic had a special beauty. The bounding leopards had become a ring of fire. Sparks flew into the trees and glowing streams festooned the branches, bathing the glade in ever-changing rainbow colors. When the king let his hand fall, the ring had faded; the leopards had gone.

Mathonwy rose to his feet. "Where are they?"

The king pointed to a tree behind the magician. On a low branch sat three cats. One was the color of copper, one as orange as a flame, the last like a pale gold star.

"Behold! Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius. Their coats have changed, but I still know who they are." The king laughed contentedly, pleased with his spell. "And now it is my turn."

Mathonwy sighed. From the folds of his cloak he drew out a slim ash stick: his wand. "What would you have me do?"

The king looked about him. "The forest has become my home. The guise of a tree would suit me well."

"You don't need my help for that," said the magician. "Shape-shifting comes as naturally to you as flying to a bird."

The king regarded his only friend. "Shape-shifting is not what I need, Mathonwy. I crave an everlasting change. If I am doomed to live forever, then I want to discard my human form and take on a more peaceful aspect."

"You want to live forever as a tree?" Mathonwy asked. "A tree without speech, without movement. What if they come and cut down the forest?"

The king considered this. "Perhaps I shall learn to move," he said with his mischievous smile. "Don't grieve, my friend. Last night I saw a boy in the clouds and I knew that he was one of mine. A future child. And, listen to this, Mathonwy. I know that he was from your line, too. This knowledge gave me a moment of great happiness. Now I feel the Red King can leave the world."

"The world and me," said Mathonwy without bitterness, for he was pleased to know that one day his bloodline would be joined with the king's.

"Don't begrudge me this favor," begged the king. "If I do it alone, then I will be tempted to return. Only you can make my transformation permanent. I am so weary, my friend. I cannot carry my sorrows any further."

Mathonwy gave a gentle sigh. "I will do as you wish. But forgive me if I do not compose the tree in a way that you imagine."

The king smiled, but although he fought his sorrow with all his strength, it began to overwhelm him and his eyes were clouded with tears.

The magician was filled with compassion for the king and began to work quickly. He touched his friend's shoulders with the tip of his ash-wand, then reached for the crown. But the thin gold band was so embedded in the king's black curls, Mathonwy let it rest where it belonged.

The king wore the robes of coarse hemp that he had worn ever since he had come to live in the forest. As he lifted his hands the rough sleeves fell back, and beneath his arms slim green shoots sprouted from his body. Mathonwy tapped the shoots with his wand and they began to thicken. The king's head rose, his body stretched, taller and taller, wider and wider. Leaves began to cover the branches; like tiny mirrors they reflected the colors of the autumn forest and the red-gold fire.

The cats watched the transformation of their master with glowing eyes. They watched the magician leap around the king, his wand a streak of sparks, his dark cloak flying, his hair a drift of thistledown. And now the cats began to howl, for their master had all but vanished; only his head remained atop a tree of dazzling splendor. And, as his dear features gradually faded, the tears that fell from his dark eyes ran a deep berry red.

"Oh, my children!" The king sighed. And then he was gone.

But the tears flowed on, coursing down the trunk, red as blood.

Mathonwy stared at the tears in dismay. He tried to stem them with his wand, but on they flowed. So, summoning all the wit, poetry, and magic that was in his soul, Mathonwy cast a spell.

"One day, my friend," he said, "your children will come to find you, and oh, what a day that will be!"

A DEADLY HOUR

Snow filled the air; thick and fast it heaped itself upon the sleeping city, almost as though it were trying to keep it safe. A blanket of down to smother the wickedness that someone was determined to let loose.

It was the second week in January, a time when snow is not uncommon, and yet this was no ordinary snowfall. On a hill above the city a boy stood with his arms wide, as if for flight. As the wind buffeted his body, clouds of snow billowed into his wide sleeves and under the green cape he wore. Tancred Torsson could summon rain, wind, thunder, and lightning, but this was the first time he had attempted snow. And why should he be standing here, in the dead of night, beckoning snow? Because three cats had climbed up to his windowsill and woken him with their calls. Slipping a cape over his pajamas, Tancred had rushed out into the dark.

The cats met him at his front door, and while his parents slept on (his father sending thundery snores through the house), he had followed the three bright creatures down a shadowy lane to a windy hillside where he could see the city lights twinkling below him. Once there, the cats stared and stared at Tancred until they had made him understand their wishes.

Tancred did not have the gift of understanding animals, but being a descendant of the Red King, he could, sometimes, follow the gist of their yowling. "Snow?" he said. "Is that what you want?"

A loud trill came from the cats, their voices blending musically.

"Never done that before." Tancred scratched his stiff blond hair. "But, hey, I'll give it a go."

The cats purred their satisfaction.

While Tancred set to work, the cats sped down the hillside into the city. The first cat was the color of a copper sunset, the second like an orange flame, the third a yellow star. They bounded lightly down alleys, through gardens, and over stone walls and fences, their paws leaving scarcely a mark on the first scattering of snow. The tall city buildings were beginning to disappear in a shroud of white silence.

This was an hour like no other. A time when the living were as quiet as the dead. A deadly hour.

The cats ran down Filbert Street. They had nearly reached their destination when a car appeared, moving slowly up the street toward them. It stopped outside number twelve and three figures stumbled out. A man, a woman, and a boy. Grumbling and exclaiming at this sudden snowstorm, they heaved bags and suitcases onto the pavement.

"We're just in time," said the woman. "Another ten minutes and it would have been too deep for the car." She climbed the steps up to her front door.

"What a welcome," muttered the man. "Let's go back to Hong Kong." He gave a gruff chuckle and slammed the car door.

The boy carried two suitcases up the steps, then turned, as if he felt something watching him. He looked across the street and saw the three cats. "It's the Flames," he said, "outside Charlie's house. I wonder what they want."

"Don't stand out there, Benjamin," said his mother. "Come inside."

Benjamin ignored her. "Hello, Flames!" he called softly. "It's me, Benjamin. I'm back."

A throaty rumble came from the cats. A growl of welcome that also held a note of complaint. "About time, too," they seemed to say.

"See you soon," said Benjamin as his mother hauled him and the cases through the door.

The cats watched the door close. When the lights came on inside number twelve, they turned their attention to the house behind them. A leafless chestnut tree stood in front of the house and they quickly climbed to a wide branch that hung outside one of the dark windows. Sitting in a row, the cats began to sing.

On the other side of the window, Charlie Bone stirred in his sleep. Someone was calling him. Was it a dream? His eyes opened. A sound he recognized came floating through the window. "Flames?" he murmured. Now he was wide awake. Leaping out of bed, he drew back a curtain and opened the window.

The sight of three shining creatures, veiled in snow, took Charlie's breath away. When he'd convinced himself he wasn't dreaming, he asked, "Aries, Leo, Sagittarius, is it really you?"

They didn't bother to reply. With soft thuds they landed on the carpet, followed by a cloud of flying snow.

Charlie closed the window. "You'd better come downstairs," he whispered. "It's a night for warm milk and maybe a slice of turkey." He glanced at a bed on the other side of the room, where a boy lay sleeping, his hair as white as his pillow.

The cats padded after Charlie as he crept downstairs. In the kitchen he warmed a pan of milk and poured it into three saucers. Deep, delighted purring filled the room as the cats lapped up the milk. As soon as it was gone, Charlie laid slices of turkey on the empty saucers.

Snowflakes whirled past the uncurtained window, glistening in the beam of the kitchen lamp.

"Something different about that snow," Charlie observed. "Should I put two and two together and guess why you've come?" He watched the cats vigorously wash themselves. I was twelve last week and where were you then? Parties don't interest you, I suppose?"

Leo, the orange cat, stopped washing and returned Charlie's gaze. Not many cats could look you in the eye like that. Leo's gaze burned with knowledge, with wildness, and with memories of a life most mortals could only dream of. Leo was nine hundred years old, as were his brothers.

Aries and Sagittarius now added their intense gaze to Leo's. Charlie had the impression that they wanted to tell him something. He would have to wake the boy upstairs if he was to understand what the cats were trying to tell him.

Three pairs of golden eyes followed Charlie out of the room. He could still feel them on his back as he climbed the stairs.

"Billy! Billy, wake up!" Charlie gently shook the white-haired boy's shoulder.

"What? What is it?" Billy opened his round ruby-colored eyes.

"Ssh! The Flames are here. I want you to come talk to them."

Billy yawned. "Oh. OK." He tumbled out of bed, still not fully awake.

"You must be quiet," warned Charlie, "or Grandma Bone will hear us."

Billy nodded and reached around for his glasses.

Billy was eight years old and a head shorter than Charlie. He could communicate with animals, but only if they allowed him to. He had always been a little fearful of the Flame cats. They knew when he was lying.

"Come on," Charlie whispered urgently.

"I've got to find my glasses," said Billy, "or I'll fall. Ah. Here they are." He pushed them onto his nose and crept after Charlie.

The cats watched the two boys enter the kitchen.

Three pairs of ears flicked toward Billy when he sat, cross-legged before the stove, neat and alert. Charlie closed the door and sprawled beside the smaller boy.

"Go on, then," said Charlie.

A sound came from Billy's throat: a soft, lilting mew.

You have news for us?

Aries replied with a growl that grew in strength the longer he held it. The other cats joined in and Charlie wondered if Billy could take in the chorus of information that came mewing and wailing at him in three different voices.

Billy didn't make a sound. With his arms tucked inside his crossed legs and his chin resting on his clasped hands, he listened attentively. Charlie looked anxiously at the door. He dared not hush the cats, but he worried that Grandma Bone would hear their yowling.

Billy frowned as the cats continued in their lilting, anxious voices. When, at last, their speech was over, Billy's eyes were wide with alarm. He turned to Charlie. "It's a warning."

"A warning?" asked Charlie. "What kind of warning?"

"Aries says that something might wake up if they can't stop . . . stop . . . er . . . another thing from being found. And Sagittarius says that if that happens, you must be watchful, Charlie."

"Watchful? But what am I supposed to watch?"

Billy hesitated. "A woman - I think. Your . . ." The next word stuck in his throat.

"My

what?"

Charlie demanded.

"Your - mother."

"My . . ." Charlie stared at Billy and then at the cats. "Why?" His voice was husky with dread. "Is someone going to make her disappear - like my father?"

Billy asked the cats, and Leo responded with an apologetic warble.

"Leo says he wishes he could tell you more," Billy interpreted. "He will help you to watch."

Leo gave several loud mews.

"He says that if the shadow has moved, then you'll know it's been released."

"What's

been released?" begged Charlie, tugging at his wild hair. "Can't they be a bit more specific?"

At that moment the door opened and a voice said, "Will someone kindly turn off that light?"

Charlie leaped up to flip the switch, and as soon as the lamp over the table had gone out, a tall man in a red bathrobe appeared. He was holding a lit candle in a brass candlestick.

"I see you have visitors." Charlie's great-uncle Paton nodded in the cats' direction. "Morning, Flames."

The cats trilled a greeting and Charlie said, "Is it really morning?"

"It's nearly one a.m.," said Uncle Paton, who didn't seem at all surprised to see Charlie and Billy downstairs at such an early hour. "I'm feeling hungry." He crossed the room and opened the fridge. "I detect an air of mystery. What's been going on?"

"The Flames came to warn me," Charlie told his uncle, "about Mom."

"Your mother?" Uncle Paton turned away from the fridge with a frown. "Did you say your

mother?"

Yes.

"And a shadow," added Billy.

Uncle Paton brought a plate of cheese from the fridge and set it on the kitchen table, beside the candlestick. "I want to know more," he said.

"Billy, tell the cats to explain," begged Charlie. "Ask them what the shadow is."

But the cats were eager to be gone. They stretched themselves and ran to the door.

"Wait!" said Charlie. "You haven't told me about the shadow."

Aries yowled and Leo scratched at the door. Charlie had no choice but to open it. And then the cats were out and bounding down the hall.

"What shadow?" Charlie whispered fiercely as he followed the cats.

Sagittarius growled. Charlie couldn't tell if it was an answer or a demand.

"Let them go, Charlie." Billy ran and opened the front door. "They've got to get somewhere else, fast. To see if the thing is found."

With a sudden chorus of trills, the Flames darted through the door and were away up the street; three bright flames swallowed by the whirling snow.

"They didn't explain," Charlie grumbled. "Now I'll never know."

"They did," said Billy. "They -"

Before he could say any more, a voice from the top of the stairs shouted, "What's the meaning of this?"

Grandma Bone was an unpleasant sight at the best of times, but after midnight she looked her worst. Her skinny frame was wrapped in a shaggy, gray bathrobe and her big feet encased in green woolen slippers. A long, white ponytail hung over her shoulder, and her sallow face had blotches of white cream dotted across it.

"Hello, Grandma," said Charlie, trying to make the best of things.

"Don't be insolent." Grandma Bone didn't like people being cheerful at night. "Why aren't you in bed?"

"We were hungry."

"Rubbish." She treated everything Charlie said as a lie. "I heard cats." She began to descend the stairs.

"They were outside, Grandma," Charlie said quickly.

She stopped and stared at the glass fanlight above the front door. "What sort of snow is that? It doesn't look normal." She had a point. There

was

something different about those spinning flakes, but Charlie couldn't have said what it was.

"It's cold, white, and wet," said Uncle Paton, stepping out of the kitchen. "What more do you want?"

"You!" snarled Grandma Bone. "Why didn't you send these boys back to bed?"

"Because they were hungry," answered her brother in a superior tone. "Go to bed, Grizelda."

"Don't you order me around."

"Suit yourself." Paton ambled back into the kitchen.

For a moment Grandma Bone remained on the stairs, glaring down at Charlie.

"I'll get a glass of water, Grandma, and then we'll go straight to bed." Charlie looked at Billy. "Won't we, Billy?"

"Oh, yes." To an orphan like Billy, Charlie's strange, quarreling family was endlessly fascinating. He nodded emphatically at Grandma Bone and added, "Promise."

Grandma Bone gave a

Hmph

of doubt and shuffled upstairs.

Charlie drew Billy into the kitchen again and asked in a whisper, "What did they say, Billy? The Flames. About the shadow?"

"They just said a word," Billy replied. "It sounded like 'listen. No, something different, an old-fashioned word for 'listen.

"Hark?" Uncle Paton suggested.

"Yes, that's it."

"That's hardly a name, dear boy." Uncle Paton bit into a hunk of cheddar. "It's more of a command. Perhaps you misheard."

"I didn't," said Billy gravely.

By now the three cats had crossed the city and were stepping lightly over the snow that had drifted against the walls of Bloor's Academy. They passed the two towers on either side of the entrance steps and kept going, along the side of the building, until they reached the end, where a high stone wall began. Ivy had taken root in the ancient stones and the cats skimmed up the creeper and dropped down into a snowy field.

On the far side of the field, the dark red walls of a ruined castle could be glimpsed. The cats became cautious. They paced carefully across the white field, their ears tuned to any sound that might come from the ruin. And then they heard the cry.

"I know what you're doing," shrieked a woman's voice. "But I can't be stopped, you fools. Did you think that snow would hinder me? Granted, it has slowed me down, but never will it stop me."

The cats moved closer. Through the great arch into the castle, they could see a dark figure, bent in half, her arms buried in snow up to her elbows. She swayed this way and that, tugging, pulling, and moaning with effort. With a sudden, deep groan, a large flat stone was heaved upright, then fell back into the snow.