The Dawn of Innovation (37 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

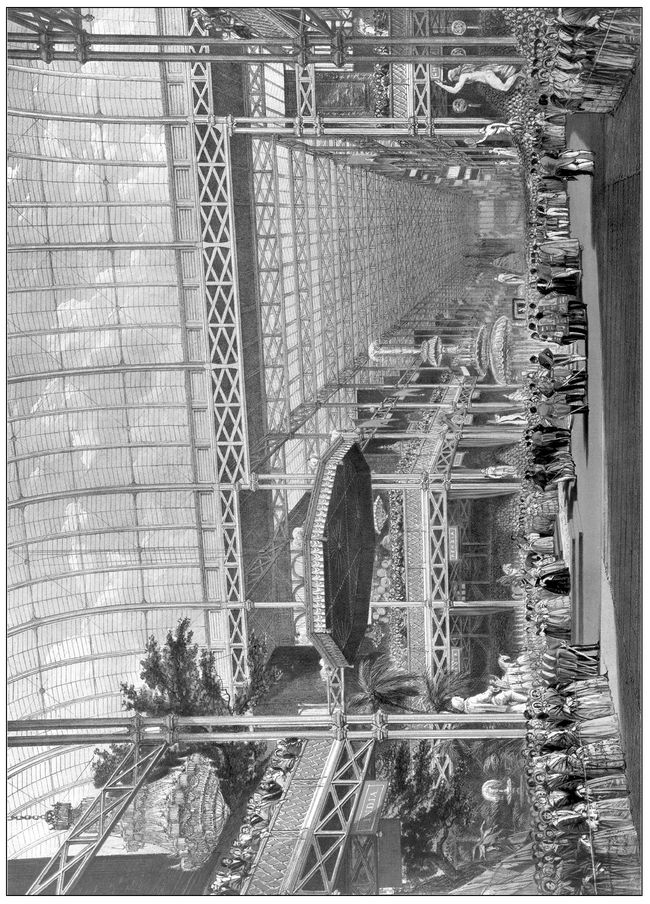

LONDON'S GREAT CRYSTAL PALACE EXHIBITION OF 1851WAS ORGANIZED by Prince Albert and his circle, and officially titled the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. That “All Nations” in the title was merely politesse, for no one could mistake that the event was a festival of self-admiration, a celebration of the global triumph of empire, British industry, and British culture.

The construction of the Exhibition Hall in London's Hyde Park was itself a great feat of engineering. More than a third of a mile long and housing 13,000 exhibitions, it was constructed of more than a million machine-fabricated, iron-framed glass sheets and set among gorgeous plantings and 12,000 fountain jets spurting as high as 250 feet. (The great engineer Isambard K. Brunel designed much of the exhibition's water system.) The plate-glass components, sufficiently interchangeable to be simply bolted together, were as astonishing as anything in the displays, pointed testimony to the continued march of British technology. They were the product of a new plate-glass rolling and annealing process patented in 1848 by James Hartley, one of Great Britain's largest glass manufacturers.

1

The massive edifice was erected in only twenty-two weeks, for just a six-month run from May through October, during which it accommodated more than 6 million visitors. When the exhibition closed in the fall, the hall was dismantled and reconstructed in a London suburb, where it remained until it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

1

The massive edifice was erected in only twenty-two weeks, for just a six-month run from May through October, during which it accommodated more than 6 million visitors. When the exhibition closed in the fall, the hall was dismantled and reconstructed in a London suburb, where it remained until it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Â

The Crystal Palace.

the great hall of the Crystal Palace during the inauguration ceremony. It was the first largescale prefabricated ferrovitreous (iron and glace) strucure in the world, prefectly suited to illustrate the preeminence of British technology.

the great hall of the Crystal Palace during the inauguration ceremony. It was the first largescale prefabricated ferrovitreous (iron and glace) strucure in the world, prefectly suited to illustrate the preeminence of British technology.

Countries with little industry to speak of paraded their treasures. The Greek exhibit displayed figures from the Parthenon and some ancient statuary, while Russians offered fabulous jewels, massive bronze candelabras, and Chinese vases that appear to be booty. Compared to such extravagances, the ragtag collection of homely objects in the American display drew quiet British jeering.

Punch

sniffed that America's “contribution to the world's industry consists as yet of a few wine glasses, a square or two of soap, and a pair of saltcellars.” In disgust, the

New York Herald

editor, James Bennett Forbes, suggested adding P. T. Barnum's “happy family” exhibit, displaying “owls, mice, cats, rats, hawks, small birds, monkeys . . . and what-not, all in one cage, and living harmoniously together.”

2

Then the gods of coincidence came up with a boat race, forever after designated the America's Cup, which quite unintentionally became a major side event of the Great Exhibition.

The Great RacePunch

sniffed that America's “contribution to the world's industry consists as yet of a few wine glasses, a square or two of soap, and a pair of saltcellars.” In disgust, the

New York Herald

editor, James Bennett Forbes, suggested adding P. T. Barnum's “happy family” exhibit, displaying “owls, mice, cats, rats, hawks, small birds, monkeys . . . and what-not, all in one cage, and living harmoniously together.”

2

Then the gods of coincidence came up with a boat race, forever after designated the America's Cup, which quite unintentionally became a major side event of the Great Exhibition.

The notion of an American-British sailing race originated with an innocuous letter from a British merchant to John Cox Stevens, the president of the New York City Yacht Club. The merchant professed himself an admirer of American pilot boats. They were descendants of the famed Baltimore Clippers that so bedeviled the British during the War of 1812, and considered the fastest sailing ships afloat. The gentleman hoped that the club might send a few at the time of the exhibition, so Englishmen would have a better opportunity to assess their merits.

3

3

John Cox Stevens was the son of John Stevens, the inventor and steamboat and railroad entrepreneur, and the elder brother of Robert, who was an entrepreneur and technical genius like their father. Stevens père earned enough from his enterprises to be a rich man but had also married into the super-rich Livingstons, allowing John Cox to spend most of his time with his boats and horses. He and his yachting friends quickly decided to take up the merchant's idea but chose to construe it as a challenge to race, rather than as a simple invitation.

The Club contracted with the big William H. Brown shipyard and a young designer George Steers to construct a racing schooner to their specifications. (Much of the risk was borne by Brown and Steers; if the boat didn't pass a series of trials in the United States and go on to win the race in England, they would be paid nothing.)

The bargain made, the new boat, named

America

, was built and passed its trials in the United States. It was captained by Dick Brown (no relation to the builder), who ran the fastest pilot boat in New York Harbor and brought his own crew.

bk

America

sailed to Le Havre in July. It was a difficult crossing, marked by alternating storms and calms, but was accomplished in nineteen days, well under the average for fast packet ships.

America

, was built and passed its trials in the United States. It was captained by Dick Brown (no relation to the builder), who ran the fastest pilot boat in New York Harbor and brought his own crew.

bk

America

sailed to Le Havre in July. It was a difficult crossing, marked by alternating storms and calms, but was accomplished in nineteen days, well under the average for fast packet ships.

Their arrival in England, at Portsmouth, was preceded by tales from the Le Havre pilots about the American craft that sailed so smoothly and so fast. A racing cutter from the Royal Yacht Squadron met

America

on the Channel, offering to escort them into the harbor. Brown accepted and immediately found himself in an impromptu race. After a brief tacking duel,

America

sailed into the harbor with the cutter far in its wake.

America

on the Channel, offering to escort them into the harbor. Brown accepted and immediately found himself in an impromptu race. After a brief tacking duel,

America

sailed into the harbor with the cutter far in its wake.

Stevens was warmly welcomed by Britain's sailing establishment and richly entertained. Although the talk was dominated by the

America

, no one offered a race. After making several direct challenges, Stevens was fobbed off with the suggestion that he enter

America

in an upcoming regatta for “all ships” of “all nations,” around the Isle of Wight, a fifty-three-mile run. It was clearly not the race he was looking for.

America

would be competing with speedy light cutters as well as schooners, with much of the race in light winds in the lee of the island, far from the conditions it had been designed for.

America

, no one offered a race. After making several direct challenges, Stevens was fobbed off with the suggestion that he enter

America

in an upcoming regatta for “all ships” of “all nations,” around the Isle of Wight, a fifty-three-mile run. It was clearly not the race he was looking for.

America

would be competing with speedy light cutters as well as schooners, with much of the race in light winds in the lee of the island, far from the conditions it had been designed for.

Irritated, Stevens took his boat out day after day intentionally showing up British yachtsmen, to the point at which the British press, always happy

to tweak the idle upper classes, was getting interested. A reporter from the

Times

watched a club race that the

America

shadowed, and wrote:

to tweak the idle upper classes, was getting interested. A reporter from the

Times

watched a club race that the

America

shadowed, and wrote:

As if to let our best craft see she did not care about them, the

America

went up to each in succession, ran to the leeward of every one of them, as close as she could, and shot before them....

America

went up to each in succession, ran to the leeward of every one of them, as close as she could, and shot before them....

Most of us have seen the agitation which the appearance of a sparrow hawk in the horizon creates among a flock of wood pigeons or skylarks, when . . . [they] are rendered almost motionless by fear of the disagreeable visitor.... Although the

America

is not a sparrow hawk, the effect produced by her apparition off West Cowes among the yachtsmen seems to have been completely paralyzing.

4

America

is not a sparrow hawk, the effect produced by her apparition off West Cowes among the yachtsmen seems to have been completely paralyzing.

4

Anxious to get home, and with no other options besides the all-comers regatta, Stevens swallowed his frustration and acquiesced to the regatta.

The day of the race, Friday, August 22, dawned with enough wind to at least give

America

a chance against the lighter cutters. At the cannon signal,

America

was caught by a sudden gust and got tangled in its cable, requiring it to strike its sails and restart. Brown still caught the first stragglers within five minutes, sailing aggressively through the pack, and within fifteen minutes was behind only three schooners and several light cutters. Shortly thereafter, the leaders entered a stretch more open to the channel winds, and

America

was finally in its element. After the second hour, it had left all the schooners in its wake and was running down the cutters one by one. Even many of the steamers carrying sightseers were having trouble keeping up. When

America

made the turn into the lighter winds for the final run, no other boat was in sight. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were watching from their yacht but, with the race obviously decided, took off for home. One steamer passing a dock was hailed from the shore: “Is the

America

first?” “Yes,” came the reply. “What's second?” “Nothing.”

5

America

a chance against the lighter cutters. At the cannon signal,

America

was caught by a sudden gust and got tangled in its cable, requiring it to strike its sails and restart. Brown still caught the first stragglers within five minutes, sailing aggressively through the pack, and within fifteen minutes was behind only three schooners and several light cutters. Shortly thereafter, the leaders entered a stretch more open to the channel winds, and

America

was finally in its element. After the second hour, it had left all the schooners in its wake and was running down the cutters one by one. Even many of the steamers carrying sightseers were having trouble keeping up. When

America

made the turn into the lighter winds for the final run, no other boat was in sight. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were watching from their yacht but, with the race obviously decided, took off for home. One steamer passing a dock was hailed from the shore: “Is the

America

first?” “Yes,” came the reply. “What's second?” “Nothing.”

5

The apparent runaway victory by

America

dominated the accounts of the race, although in reality it won by the slimmest of margins. With only five miles to go, the wind died, and

America

could barely creep forward, as

a lightweight cutter, the

Aurora

, slowly closed the gapâ“bringing the wind with her,” in Brown's rueful phrase.

6

That last five miles may have taken three hours, but the wisps of breeze finally stiffened enough that the

America

slipped over the line with just eight minutes to spare.

America

dominated the accounts of the race, although in reality it won by the slimmest of margins. With only five miles to go, the wind died, and

America

could barely creep forward, as

a lightweight cutter, the

Aurora

, slowly closed the gapâ“bringing the wind with her,” in Brown's rueful phrase.

6

That last five miles may have taken three hours, but the wisps of breeze finally stiffened enough that the

America

slipped over the line with just eight minutes to spare.

The British were as magnanimous in defeat as they had been reluctant to engage. For the yachting community, however, according to the

Times

, the loss had been like “a thunderclap . . . the sole subject of conversation here, from the Royal Yacht Commodore . . . to the ragged and barefooted urchin.” A wealthy American commented to a lady on British courtesy and the lack of mortification her friends seem to feel. “âOh,' said she, âif you could hear what I do, you would know that they feel it most deeply.'”

bl

7

Times

, the loss had been like “a thunderclap . . . the sole subject of conversation here, from the Royal Yacht Commodore . . . to the ragged and barefooted urchin.” A wealthy American commented to a lady on British courtesy and the lack of mortification her friends seem to feel. “âOh,' said she, âif you could hear what I do, you would know that they feel it most deeply.'”

bl

7

O

N THE SAME DAY AS

AMERICA

'S VICTORY, AN AMERICAN SUCCEEDED IN opening a famous, exquisitely crafted, and “unpickable” British Bramah lockâmeeting a challenge that had stood for forty years. (Joseph Brahma was a great British machinist, yet another graduate of the Henry Maudslay school of advanced precision manufacturing.) The lock breaker was Alfred C. Hobbs, a talented huckster with an excellent understanding of machine manufacturing. He adroitly downplayed that his lock-breaking feat took more than two weeks and then offered $1,000 to any British locksmith who could open his own machine-made locks. When no one could meet his challenge, he collected the exhibition's lock medal and almost immediately made plans to open a factory in England.

N THE SAME DAY AS

AMERICA

'S VICTORY, AN AMERICAN SUCCEEDED IN opening a famous, exquisitely crafted, and “unpickable” British Bramah lockâmeeting a challenge that had stood for forty years. (Joseph Brahma was a great British machinist, yet another graduate of the Henry Maudslay school of advanced precision manufacturing.) The lock breaker was Alfred C. Hobbs, a talented huckster with an excellent understanding of machine manufacturing. He adroitly downplayed that his lock-breaking feat took more than two weeks and then offered $1,000 to any British locksmith who could open his own machine-made locks. When no one could meet his challenge, he collected the exhibition's lock medal and almost immediately made plans to open a factory in England.

Hobbs's demonstration came just a few weeks after Cyrus McCormick's reaper had decisively bested a feeble array of local competitors in a series of field tests. The usually anti-American

Times

, which had earlier derided McCormick's machine as “a cross between a flying machine, a

wheelbarrow, and an Astley chariot,” abruptly changed its tune: “The reaping machine from the United States is the most valuable contribution from abroad, to the stock of previous knowledge that we have yet discovered,” predicting that it would “amply remunerate England for her outlay connected with the Great Exhibition.”

8

Times

, which had earlier derided McCormick's machine as “a cross between a flying machine, a

wheelbarrow, and an Astley chariot,” abruptly changed its tune: “The reaping machine from the United States is the most valuable contribution from abroad, to the stock of previous knowledge that we have yet discovered,” predicting that it would “amply remunerate England for her outlay connected with the Great Exhibition.”

8

But the praise heaped on reapers and locks were far eclipsed by the plaudits for Sam Colt's repeating firearm exhibit; even the Duke of Wellington, a regular visitor to Colt's booth, was heard proclaiming the virtues of repeating firearms. Another gun maker, the Vermont firm of Robbins and Lawrence, conducted a well-attended demonstration showing how its machine-made rifles could be disassembled, their parts mixed up, and then randomly reassembled by an unskilled workman using only a screwdriverâa feat that British gunsmiths had long declared impossible. Robbins and Lawrence won the exhibition's firearms medal, while Colt, like Hobbs, let it be known that he too would open a plant to bring American technology to Great Britain.

It was sweet turnaround for the Americans. Even

Punch

gleefully switched to mocking punctured British pride:

Punch

gleefully switched to mocking punctured British pride:

Yankee Doodle sent to town

His goods for exhibition;

Everybody ran him down,

And laughed at his position;

They thought him all the world behind;

A goney muff or noodle,

Laugh on, good people,ânever mindâ

Says quiet Yankee Doodle

CHORUS Yankee Doodle, etc.

His goods for exhibition;

Everybody ran him down,

And laughed at his position;

They thought him all the world behind;

A goney muff or noodle,

Laugh on, good people,ânever mindâ

Says quiet Yankee Doodle

CHORUS Yankee Doodle, etc.

Â

Their whole yacht squadron she outsped,

And that on their own water,

Of all the lot she went ahead,

And they came nowhere arter

Your gunsmiths of their skill may crack,

But that again don't mention;

I guess that Colt's revolvers whack

Their very first invention. . . .

But Chubb's [another British lock maker] and

Bramah's Hobbs has pick'd,

And you must now be viewed all

As having been completely licked

By glorious Yankee Doodle.

CHORUS Yankee Doodle, etc.

And that on their own water,

Of all the lot she went ahead,

And they came nowhere arter

Your gunsmiths of their skill may crack,

But that again don't mention;

I guess that Colt's revolvers whack

Their very first invention. . . .

But Chubb's [another British lock maker] and

Bramah's Hobbs has pick'd,

And you must now be viewed all

As having been completely licked

By glorious Yankee Doodle.

CHORUS Yankee Doodle, etc.

Other books

Blood Relatives by Ed McBain

The Hawk And His Boy by Christopher Bunn

Wild Cat by Jennifer Ashley

The Thousand Year Curse (The Curse Books) by Taylor Lavati

Temporary Husband by Day Leclaire

Crown Park by Des Hunt

A Grid For Murder by Casey Mayes

Varius: #9 (Luna Lodge) by Madison Stevens

Vampire Girl by Karpov Kinrade

The Legacy by Fayrene Preston