The Dawn of Innovation (41 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

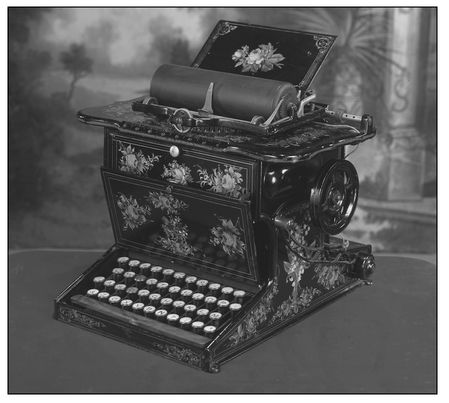

By the 1890s, there was a host of competitorsâHall Typewriters, American Writing Machine, Oliver, L. C. Smith & Brothersâand the industry, unlike sewing machines, evolved into a manufacturing competition. Major advances were made in ball bearings, in the use of new materialsâvulcanized rubber, glass, sheet metal, celluloseâand in new machinery, like pneumatic molding devices and “exercise machines” that would put the finished products through grueling tests of high-speed typing. All of the critical parts were interchangeable to a high degree, but given the large number of parts, assembly and adjustment was one of the most important steps in the manufacturing sequence. Parts were not filed to fit, as in the old armories, but were manufactured for easy adjustment by screws or other devices. It was the same principle as the adjustable escapement setting in Terry's shelf clock, but carried to the nth degree.

36

WALTHAM WATCHES36

Although watchmaking seems a natural extension of the brass clock industry, the required precision at very small dimensions created an entirely different order of technical challenge.

The father of the American watch industry was Aaron Dennison, an entrepreneur and skilled mechanic who, in 1849, together with clockmaker Edward Howard and a small coterie of investors, set out to mass-produce quality watches. At the time watchmaking was the province of British handcraft artisans. Individual parts were farmed out to subspecialists to be later fitted and assembled by masters of the trade. Although he was committed to machine manufacture, Dennison recruited a number of British craftsmen for their know-how and their highly specialized tools.

The company started in a corner of Howard's clock factory, but in 1854 Dennison built a factory in Waltham and dubbed the company the Waltham Watch Company. By the time he ran out of money in 1857, he had produced some 5,000 watches. Most of the output was by traditional methods, although the company worked on developing new machinery from the earliest days. An investor bought the company at auction and

supplied the capital to maintain its development. A new factory superintendent hired in 1859, Ambrose Webster, created a highly rational, lightly mechanized, new production system just in time for a boom in watch sales from the sudden Union military demand and the disruption of British trade. By 1864, with 38,000 watch sales in a single year, the company was solvent and had capital to spare.

supplied the capital to maintain its development. A new factory superintendent hired in 1859, Ambrose Webster, created a highly rational, lightly mechanized, new production system just in time for a boom in watch sales from the sudden Union military demand and the disruption of British trade. By 1864, with 38,000 watch sales in a single year, the company was solvent and had capital to spare.

From that point, Waltham Watch commenced a single-minded, three-decade drive to fully automate watch production. Various competitors entered the industry from time to time, most of them falling by the wayside as Waltham relentlessly drove down prices and improved its quality, along the way creating entirely new swathes of production technology. The Elgin Watch Company, founded in 1864 by former Waltham mechanics, was the only one of the era's start-ups to survive in the long term.

Among Waltham's many process inventions, they were the first to adopt dimensioned gaugingâbased on precise measurements instead of tests of fittingâsince the small size of watch parts made traditional gauging impractical. Needle gauges tested the diameters of jeweled hole collars, eventually to accuracies of 1/17,000 inch. By the 1880s, all screws, by far the most common watch part, were produced internally with automatic screw-cutting machines. Escapement wheel-cutting machines carried fifty blanks at a time and were completely self-acting, making ninety cuts per wheel with three steel and three sapphire cutters. (The hardness of sapphire eliminated the need to polish the finished escapement teeth.) The list of new machining and control processes could be extended almost indefinitely.

Much as in typewriters, the final adjustment and tuning of the watch was a critical step. Tiny shifts in the ratio of balance weight and hairspring strength affected accuracy. Multiple set screws tuned the balance between all the critical parts. Adjustment of the cheaper watches was often left to dealers, but adjustment on top of the line products could take months. Among other things, they had to assure consistent time keeping at temperature extremes. With sales of 18 million watches by 1910, steadily falling prices and costs, and the most precise production machinery in the world, Waltham wrote a unique chapter in the annals of automated manufacture.

37

37

A

RMORY PRACTICE-STYLE OF MANUFACTURING WAS AN IMPORTANT THREAD of American industrial development, but it became a major feature of the economy only with the mass manufacture of automobiles, kitchen appliances, and other complex national consumer products in the twentieth century. As we have seen, the intense interest of the British in American gun making, their dubbing it the American system of manufacturing, and American pride in making such a positive impression naturally led industrial historians, at least implicitly, to treat armory practice as an important driver of nineteenth-century growth.

bo

RMORY PRACTICE-STYLE OF MANUFACTURING WAS AN IMPORTANT THREAD of American industrial development, but it became a major feature of the economy only with the mass manufacture of automobiles, kitchen appliances, and other complex national consumer products in the twentieth century. As we have seen, the intense interest of the British in American gun making, their dubbing it the American system of manufacturing, and American pride in making such a positive impression naturally led industrial historians, at least implicitly, to treat armory practice as an important driver of nineteenth-century growth.

bo

The real story is that in a labor-short country, Americans were quick to resort to mechanized solutions to a wide range of production problems, like the portable sawmills in midwestern forests, or the high-pressure lard-processing systems, or the steam-powered threshers of the 1870s, processing 5,000 bushels a day on Great Plains factory farms, pouring them directly into freight cars lined up on the farms' own rail spurs.

The overwhelming proportion of nineteenth-century American mechanization efforts went into basic processing industries, not precision manufacturing. Food and lumber processors were 60 percent of all power-using manufacturing industries in 1869. Add textiles, paper, and primary metal industries like smelting, and the number rises to 90 percent. Industries that would plausibly lend themselves to armory practice methodsâfabricated metal products, furniture, machinery, and instrumentsâaccounted for only 7.5 percent of 1869 manufacturing power demand. And the mere use of power machinery doesn't qualify as armory practice. It's safe to say most furniture and metal fabrication shops stuck with craft-based methods. There are only small differences in the data in the 1889 census.

38

38

All industries were moving to higher levels of precision as the century passed the halfway point. Continuous-flow processing, as in lard, grains,

and later petroleum, imposes requirements for precise valves, gauges, temperature control devices, and protection from contaminants. And those requirements mount exponentially as volumes and levels of customer sophistication rise in tandem. It took new generations of superb machinists, and superb new tooling, to meet those standards, but for the most part, it had little to do with armory practice.

and later petroleum, imposes requirements for precise valves, gauges, temperature control devices, and protection from contaminants. And those requirements mount exponentially as volumes and levels of customer sophistication rise in tandem. It took new generations of superb machinists, and superb new tooling, to meet those standards, but for the most part, it had little to do with armory practice.

One index of the pervasiveness of armory practice is the sales of precision metal-shaping machinery from Brown & Sharpe, the quintessential armory-practice vendor. The company sold almost 24,000 machines between 1861 and 1905. Of that total, it took until 1875 to sell the first 1,000 and until 1883 to sell another 1,000. That is consistent with the picture of armory-practice industries expanding very late in the century before its apotheosis in the Model-T plants.

39

39

Mid-century America was still a predominately agricultural country. On the eve of the Civil War, only 16 percent of the workforce was in manufacturing.

40

They worked in grain milling, meatpacking, lard refining, turning logs into planks and beams, iron smelting and forging, and making steam engines and steamboats, vats and piping, locomotives, reapers and mowers, carriages, stoves, cotton and woolen cloth, shoes, saddles and harnesses, and workaday tools. These were the industries in which America's comparative advantage loomed largest and were the ones that dominated American output. It was the drive to mass scale in those industries, by a wide variety of strategies and methods, that was the real American system, or perhaps the American ideology, of manufacturing.

America in 1860: On the Brink40

They worked in grain milling, meatpacking, lard refining, turning logs into planks and beams, iron smelting and forging, and making steam engines and steamboats, vats and piping, locomotives, reapers and mowers, carriages, stoves, cotton and woolen cloth, shoes, saddles and harnesses, and workaday tools. These were the industries in which America's comparative advantage loomed largest and were the ones that dominated American output. It was the drive to mass scale in those industries, by a wide variety of strategies and methods, that was the real American system, or perhaps the American ideology, of manufacturing.

The Civil War violently disrupted economic growth, but by finally resolving the sectional conflict, and excising the cancer of slavery, it removed the last important obstacle to continental expansion and vigorous industrialization. Abraham Lincoln came out of the old Whig tradition of Henry Clayâegalitarian, proâmanufacturing and protective tariffs, pro-education, and proâcanals, roads, and interior development. His favorite speech in a pre-election lecture tour was on discoveries and inventions. In his famous

1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln stressed the economic perils of the extension of slavery as much as he did the system's moral depravity. Extending slavery into western territories, he insisted, would inevitably drive the wages of free working men to the slave standard. Those were not trumped-up fears. Throughout the border and “blue grass” states, like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, there were at least a hundred major iron plantations, with predominately slave labor, turning out quite decent iron. The admixture of white workers, often about a quarter of the workforce, were themselves virtually enslaved by the proverbial company store and the hard-driving boss characteristic of the plantation culture.

41

1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln stressed the economic perils of the extension of slavery as much as he did the system's moral depravity. Extending slavery into western territories, he insisted, would inevitably drive the wages of free working men to the slave standard. Those were not trumped-up fears. Throughout the border and “blue grass” states, like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, there were at least a hundred major iron plantations, with predominately slave labor, turning out quite decent iron. The admixture of white workers, often about a quarter of the workforce, were themselves virtually enslaved by the proverbial company store and the hard-driving boss characteristic of the plantation culture.

41

During one of the darkest periods of the War, in 1862, the Republican Congress passed one of the great development programs in American history. The Homestead Act allowed any citizen, including single women and freed slaves, to take possession of virtually any unoccupied tract of public land for a $12 registration and filing fee. Live on it for five years, build a house, and farm the land, and it was yours for just an additional $6 “proving” fee. Over time, the act helped settle some 10 percent of the entire land mass of the United States. Senator Justin Morrill's (R-VT) 1862 land-grant college act awarded each state a bequest of public lands that it could sell to finance state colleges for the agricultural and industrial arts. No other country had conceived the notion of educating farmers and mechanics, and the Morrill Act schools are still the foundation of the state university systems.

The 1862 Pacific Railway Act made yet another lavish grant of public lands to finance a railway line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, a dream of the pro-development party for more than twenty years. The project was scarred by financial problems and scandal but was actually completed more or less as its promoters promised and surprisingly close to the original schedule. Over time, its development impact justified the airiest promises of its supporters. The Republican/Whig agenda was rounded out with major tariff increases and a federal banking act that, for all its flaws, got the country through the war and its financial aftermath.

Development economists speak of a “takeoff” point when an economy is poised for a long-term ratchet upward in growth. The United States was

clearly at or approaching such a point in 1860, but the progression was violently disrupted by the war. When growth resumed at the end of the 1860s, it was accompanied by dramatic turns in the economy that are still not completely understood. The 1870s was a time of jagged economic ups and downs, including a steep railroad-led crash in 1874 and an equally sharp recovery late in the decade. But over the full decade, nominal growth (not adjusted for inflation), was 3.9 percent, or about the long-term average.

bp

clearly at or approaching such a point in 1860, but the progression was violently disrupted by the war. When growth resumed at the end of the 1860s, it was accompanied by dramatic turns in the economy that are still not completely understood. The 1870s was a time of jagged economic ups and downs, including a steep railroad-led crash in 1874 and an equally sharp recovery late in the decade. But over the full decade, nominal growth (not adjusted for inflation), was 3.9 percent, or about the long-term average.

bp

The surprise came when economic historians adjusted the 1870s data for price inflation. In the modern era, we assume moderate price inflation is a normal condition, so “real” (inflation-adjusted) growth is always somewhat lower than nominal growth. But when the price adjustment was applied to the 1870s data, output

rose

by nearly 60 percent. In other words, prices

fell

, and quite substantially, through most of the decade even as output soared. The deflation was felt by almost everyone as a dreadful, and extremely disruptive, experience. It was a period of extraordinary social unrest. The year 1877, for reasons that are obscure, saw riots in most major cities, and Pittsburgh mobs put the torch to virtually all the main installations of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The phenomenon of real prices falling even as real output rose continued through most of the 1880s.

rose

by nearly 60 percent. In other words, prices

fell

, and quite substantially, through most of the decade even as output soared. The deflation was felt by almost everyone as a dreadful, and extremely disruptive, experience. It was a period of extraordinary social unrest. The year 1877, for reasons that are obscure, saw riots in most major cities, and Pittsburgh mobs put the torch to virtually all the main installations of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The phenomenon of real prices falling even as real output rose continued through most of the 1880s.

Other books

The Perils of Praline by Marshall Thornton

Dorothy Garlock - [Annie Lash 03] by Almost Eden

Crazy by Benjamin Lebert

Snowboard Showdown by Matt Christopher

Keep It Pithy by Bill O'Reilly

Dead Irish by John Lescroart

Unlike Others by Valerie Taylor

Naked Submission by Trent, Emily Jane

When Grnadfather Journeys Into Winter by Craig Kee Strete

How a Mother Weaned Her Girl from Fairy Tales by Kate Bernheimer