The Dawn Country (18 page)

Authors: W. Michael Gear

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Native American & Aboriginal

Koracoo placed her feet carefully, so as not to disturb any tracks, and circled around to stand over the dead man’s head.

Sindak could tell he’d been clubbed in the back of the head, and in the face. His nose and cheekbones had been crushed by the blow. Congealed blood filled the hollow. His half-open eyes had frozen in a surprised stare.

Sindak said, “Is that the guard Wrass killed?”

Almost simultaneously, Baji and Tutelo answered, “Yes.”

“Did you see it happen?” Sindak asked.

Baji looked at him as though he were an idiot. “We were sitting right there. How could we have missed it?”

“Oh. I see.”

Gonda walked over to stand beside Koracoo. A thin layer of ash coated his round face and painted a dark line across his heavy brow. Softly, he said, “This isn’t good, Koracoo.”

“What isn’t good?”

“This entire area is a morass of crisscrossing trails. All night long, hundreds of warriors tramped around obliterating each other’s tracks. Then Wind Mother whirled ash over everything.” He spread his arms in a gesture of futility. “I don’t know how we’re ever going to find—”

“Don’t give me excuses,” she replied coldly. “Start looking.”

Gonda clenched his jaw, nodded, and walked away.

“Mother?” Odion was shaking, but just barely. Only his shoulder-length black hair quivered. “Gannajero’s camp was over there, where those dead bodies are.” He pointed with the stiletto.

Koracoo turned. The bodies sprawled beside a smoldering fire pit. Next to it, a pot hung from a tripod, and a large woodpile stood beside it. “Is that the pot Wrass poisoned?”

“Yes.”

“Where did he get the poison?”

Tutelo piped up and proudly said, “Zateri found it, Mother. She knows Spirit plants. As we marched, she collected thorn apple seeds, swamp cabbage root, and spoonwood leaves. She hid them in her legging.”

Sindak’s heart twinged. He hadn’t known the girl well. Zateri was a chief’s daughter, not allowed to fraternize with ordinary warriors, but he remembered her bright smile and sparkling eyes. She’d been studying to become a Healer. How strange that she’d first use her knowledge to kill … and thereby save her friends.

Wakdanek frowned. “Even small amounts of those plants would be enough to kill several people.”

“And she collected a bag this big.” Tutelo put both her fists together to show the size.

Wakdanek stood for a moment, staring at the pot, then walked toward it. While he knelt and sniffed the contents, Sindak scanned the forest. Between the trees, scrub thickets of nannyberry bushes and prickly ash saplings spiked up. To the south, he could see the hill where they’d hidden last night; it appeared and disappeared in the shifting haze.

Koracoo suddenly looked down at the war club in her hand and frowned. After a few instants, she switched it to her other hand, as though it had grown too hot to hold.

“Koracoo?” Sindak asked. “What’s happening?”

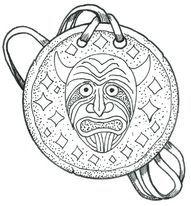

War Chief Cord caught the panic in his voice and stared hard at Koracoo; then his gaze dropped to CorpseEye. Like every other warrior in the world, he probably knew the war club’s magical reputation.

Koracoo didn’t answer. As though CorpseEye was tugging her to the north, she turned toward the long rocky ridge covered with spruces and white walnuts that sloped down to the river. “What’s down there, Odion? Where the rocky hill meets the water?”

The boy pulled his moosehide blanket tightly around his shoulders. “I don’t know. We never went over there.”

War Chief Cord said, “It’s a canoe landing. Forty or fifty canoes were beached there last night. I—”

Wakdanek interrupted, calling, “This pot was poisoned, all right. In addition to everything Tutelo named, Zateri also added a good deal of musquash. The parsnip smell is very strong.”

Koracoo slowly worked her way toward him, searching for anything in the frost or wind-blown ash that might be significant. Sindak, Cord, and Towa placed their moccasins in her tracks, as though it would make a difference in a clearing covered with ash-filled indentations.

Behind him, Sindak heard children walking, but didn’t turn to look. His gaze had focused on the dead men around the campfire.

Koracoo stepped wide around a looted pack. Broken strings of shell beads filled the bottom and sprinkled the ash-sheathed frost. She passed the bodies and went to the stew pot where Wakdanek stood.

When Sindak closed in on the first body, his eyes narrowed. Beneath the ash, the man’s arms were twisted at impossible angles, suggesting he’d died in convulsions. He looked at the others. One man, a muscular giant, still had his hands clutched around his own throat. Their deaths had not been easy.

Towa slowed down and waited for Sindak to catch up, then said, “Isn’t that War Chief Manidos?”

“From the Mountain People?” Sindak studied his contorted features. “Maybe. I’m not sure.”

Last summer, Manidos had assaulted Atotarho Village with over five hundred men. Atotarho’s War Chief, Nesi, had organized a brilliant defense and driven Manidos back; then they’d pursued his fragmented war party for two days. Sindak and Towa had been there. Nesi’s warriors had killed over half of Manidos’ men before they’d reached home.

“Were all of these warriors Gannajero’s men?” Koracoo asked.

Baji walked around to the body of a tall skinny warrior and said, “This one was. His name was Chimon. I don’t know about the others. She hired a lot of new men last night.”

“Odion may know, Mother,” Tutelo said. She called, “Odion? We need you.”

Sindak twisted around and spied Odion standing at the edge of the clearing, alone, watching them with half-squinted eyes.

The boy shook his head.

“Odion, we need you,” Tutelo repeated.

He didn’t move.

Koracoo tilted her head, examining her son. She called, “Odion? Come here.”

Sindak was twenty paces away, and he could see the boy start to shiver violently.

Wakdanek moved to stand beside Koracoo. The ash had stuck to the bones of his starved face, giving it an oddly shaded, almost skeletal appearance. “I’m not sure that’s a good idea, War Chief.”

“Why not?”

“Sometimes it does more harm than good to force a child to face—”

“Life?” she asked. “To force him to face life? He must, Wakdanek, especially when it isn’t easy. The sooner the better.”

“Odion?”

Koracoo ordered. “Come over here. Now.”

Gonda walked up behind Odion, said something to him, and put a hand on his shoulder, pushing him forward. The boy stiffly stepped out with Gonda at his side.

A dull thud sounded, followed by a grunt, and Sindak spun around to see Baji level a kick at Chimon’s head. Stiff with death, and frozen to the ground, the head barely moved. Baji clenched her jaw and kicked it again, then stepped down to his middle and leveled a brutal kick at the dead man’s privates. Her eyes took on a savage glow. She drew back and kicked him again as hard as she could.

Sindak whispered to Towa, “That little girl is quickly becoming my hero.”

“Well, enjoy it. A few summers from now, I suspect you’re going to be looking into her eyes across a bow. If she has the chance, she’ll shoot you through the heart and do the same thing to your dead body.”

“You’re in

such

a bad mood today. I wish—”

“Odion?” Gonda’s voice made Sindak and Towa swing around. Odion had stopped dead in the trail and was staring unblinking at the dead warriors.

“Why did you stop? Keep walking, Son,” Gonda said. “Your mother needs you.”

Odion took a new grip on his stiletto and obeyed, but the boy who’d been so brave yesterday looked like he was about to shatter into a thousand pieces.

C

ord grimaced as he watched Odion approach. The boy’s terror affected even him. His stomach muscles clenched tight.

When Odion got to within two paces of the dead bodies, he stared at the muscular giant who still had his hands around his throat, and a small cry of terror escaped his lips.

“No!”

he shrieked.

“No, no!”

Odion backpedaled, slammed into Gonda, and wildly shoved past him. As he charged for the trees, he pulled the blanket from his shoulders and threw it to the ground.

“Odion?” Baji yelled, and ran after him. “Odion, he’s dead! He can’t hurt you again. He’s dead!”

Baji caught Odion at the edge of the trees and wrapped her arms around him, holding him tightly while he sobbed against her shoulder.

Koracoo and Gonda stared at each other. After several agonizing moments, Koracoo turned toward the dropped moosehide blanket and said, “Where did Odion get that blanket?”

Gonda shook his head, and murmured, “I don’t know. I just assumed—”

“I think that man gave it to him.” Tutelo pointed to the muscular giant. Her pretty face had a look of concentration.

Koracoo glanced at the man, then back at Tutelo. “Why do you think that?”

“Odion didn’t have that blanket when he left camp with that man last night. But he did when I saw him later.”

“He left camp with this … this man?” Horror was slowly congealing on Koracoo’s face.

As the probable truth filtered through Gonda’s veins, his face flushed.

“Yes, Mother. Kotin told Odion that he had to go. And he told that man, I think his name was Manidos, that he would refund half the price if Manidos didn’t like Odion.”

Koracoo’s fingers tightened around CorpseEye in a death grip, but before she could say anything, Gonda lifted his war club, stalked over to Manidos, and viciously began pounding the dead man’s skull to bloody pulp.

Hehaka yelled, “What are you doing? You can’t do that! He deserves to be buried with honor. He was a

war chief

!”

“Was he?” Gonda asked in a matter-of-fact voice. “Well, then, he does deserve more.”

Gonda set his war club aside, pulled his chert ax from his belt, and hacked the man’s head off.

Hehaka’s mouth dropped open in shock, and Tutelo leaned against Koracoo’s leg to watch her father with wide eyes.

“Wakdanek,” Gonda ordered, “build up that fire.”

“Why?”

“Because I asked you to.”

“Very well,” Wakdanek replied uneasily, and knelt. As he pulled a stick from the pile and began separating out the warmest coals from last night’s fire, he kept glancing at Gonda.

Koracoo walked over to Gonda and whispered, “Be thorough.”

Gonda grabbed the severed head by the hair, swung it up, and hurled it toward the fire pit. The head thudded soddenly against the ground, rolled, and came to rest staring up at the morning sky. “Oh, I plan to. His afterlife soul is doomed.”

Gonda bent over the left arm and brutally began hacking it apart with the ax.

Sindak squinted at Gonda for several moments, then called, “Do you need to do this yourself, or can I help?”

“Take the legs,” Gonda said.

Sindak pulled his chert knife and went to work. He sliced through the muscles, then sawed down to the hip joint. When he’d severed the right leg, he moved to the left.

Towa said, “I’ll take care of the pieces.”

He picked up the leg and dragged it out into the middle of the camp where a flock of crows squawked, dropped it, and returned.

Cord was an outsider. It was not his place to interfere unless asked to do so, but … he walked around to crouch near Gonda. “Tell me what to do.”

Without even looking up, Gonda said, “The other arm.”

Cord pulled his knife from his belt and knelt near the dead man’s shoulder. He worked in utter silence, slicing through the meat toward the joint, neatly disconnecting the arm in fluid strokes.

Gonda was focused completely on the task at hand, and Cord heaved a sigh of relief. When Koracoo had asked Cord’s opinion, he’d felt Gonda’s anger like a knife in the air. It was a simple courtesy. They were both war chiefs. Koracoo wanted him to know that despite the fact that he had willingly subordinated himself to her authority on this war walk, she considered him to be an equal. Cord appreciated the gesture.

Just as Cord finished severing the last bit of sinew, he heard the whimper. It was very faint, as though coming from beneath a pile of hides, almost not there—but he swore it was more than the cries of the grieving Dawnland People. He straightened up, and his gaze drifted over the broken pots, torn blankets, and looted packs that scattered the camp.

Nothing moved, except people and the feasting birds.

From the edge of his vision, he saw Wakdanek blowing on the coals. They reddened quickly, and flames licked up around the wood. He added more branches.

Towa grabbed one arm, and the other leg, and hauled them to different areas of the camp.

Gonda rose, and Cord glanced up. The man looked like he was ready to burst at the seams, but he gave Cord a grateful nod. Cord nodded back.

Gonda grabbed the arm Cord had severed and, with a hoarse cry, swung it around in a circle, then flung it as far away as he could. The arm cartwheeled across the frozen ground.

Cord wiped his bloody knife blade on the dead man’s cape and studied Gonda. He’d turned his back to the children and stood with tears running down his cheeks as he gazed out across the camp.