The Dawn Country (15 page)

Authors: W. Michael Gear

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Native American & Aboriginal

The wolves pricked their ears. Sindak saw one, probably the lead female, lift a foot uncertainly and peer directly at Wakdanek.

“My brothers,” Wakdanek said softly. “I saw a herd of deer just beyond that rise over there.” He pointed. “Please go hunt them. We are your relatives. We don’t want to harm you.”

Sindak sneaked around until he could see two big males hiding behind a head-high pile of windblown leaves that had frozen against a rock outcrop. Wakdanek stood five paces from them. Had they wanted, the animals could have knocked him down and gutted him before he’d run three steps.

One of the wolves barked at Wakdanek; then the entire pack let loose in a spine-tingling chorus.

The skin at the back of Sindak’s neck crawled. He cautiously worked his way over to where Towa stood.

When Sindak got close enough, he could see Towa’s wide-eyed expression. He whispered, “You look petrified.”

“No. I’m just annoyed that my bladder is weaker than I thought.”

The eerie bark-howling conversation continued for another twenty heartbeats; then Wakdanek let out an authoritative series of barks, and the pack went utterly silent. As a final act, Wakdanek started growling. The low deep-throated sound made Sindak long to run. The sensation of threat rode the air.

Sindak watched in disbelief as the female loped away, followed by most of the pack. The two big males remained for a time longer; then they, too, chased after the pack.

Wakdanek propped his hands on his hips and expelled a breath. He made no moves to return to camp. He just stared out at where the wolves trotted away through the darkness.

Sindak softly called, “Do you do cat calls? I’ve always wanted to shoot a cougar.”

Wakdanek jumped when Sindak walked out of the shadows five paces from him.

The Healer squinted. “I didn’t even see you out there! Where’s your frien—”

“Here.” Towa stepped from the trees to Wakdanek’s left.

Wakdanek swung around so fast he stumbled and put a hand to his heart. “Blessed Spirits.”

“So … ,” Towa said. “We scared you, but the wolves didn’t?”

“I am Wolf Clan. Wolves are my brothers. I find humans a lot more frightening.”

“Oh. Me, too. I’m a warrior.” Sindak frowned when Wakdanek didn’t respond. He made an airy gesture with his war club. “As you are, yes?”

“I’m a Healer,” Wakdanek replied. “For me there is no glory in wounding or killing people.”

Towa said, “You must find that truly mystifying, eh, Sindak?”

Sindak scratched the back of his neck with his war club. “Yes. The only joy in war is coming home to a woman with wide adoring eyes who wants to know how many people you killed.”

Towa stared at him. “Don’t tell me that Puksu greeted you that way? I don’t believe it.”

“Puksu? Hardly. She was always sitting at her mother’s fire when I arrived home, bad-mouthing me before she even knew I’d disgraced myself in battle.”

Puksu had recently divorced him, thank the Spirits. He was heartily glad to be rid of her constant belittling voice. Even now he could hear her whine in his head:

What did you do this time, my husband? Shoot one of our own men in the back?

Wakdanek asked, “Who is Puksu?”

“My former wife, the Soul-Eater.”

“Ah.”

Sindak scowled at the darkness for a while before he said, “Come on; let’s get back to camp. If we’re attacked by humans out here, I doubt Wakdanek’s barks and howls will save us.”

Sindak let Wakdanek get several paces ahead; then he grabbed Towa’s arm to stop him and whispered, “I trust that you’ve decided to tell me more about your secret orders?”

Towa looked like a condemned man waiting for the ax to fall. “Give me some time. I need—”

“To figure out what treachery Atotarho has planned?”

“I wish you wouldn’t finish my sentences. It’s—”

“Unnerving.” He released Towa’s arm. “Especially when I’m right.”

A

s the howling of wolves penetrated his sleep, Gonda flailed weakly and heard Sindak say,

“Go back to your blankets, Wakdanek.”

Gonda flopped to his opposite side and slowly sank back into the jumbled dream. Memories collided, showing him fragments out of sequence and time … .

I crouch in the prisoners’ house in Atotarho Village.

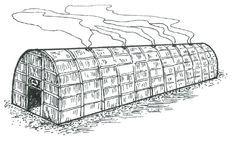

Wind gusts outside and breathes through the wall behind me, chilling my back. I wrap my cape more tightly around my shoulders, but I’m not going to be warm tonight, or perhaps, for the next moon. The damp, cold house stretches forty hands long and twenty wide. The walls are not of bark construction, but sturdy oak planks reinforced with cross-poles. The odor of mildew pervades the dark house, and insects—or perhaps they are mice—skitter across the floor. Koracoo sits on the floor two paces away with her back against the wall. In the moonlight that penetrates around the door, I can see the outline of her body. No one but me would realize how desperately worried she is. I see it in the tension in her shoulders and the way her jaw is set slightly to the left.

“They can’t be that far ahead of us,” I say. “The tracks were only one day old, and it looked like the warriors were herding eight or nine children. That many captives slow men down.”

Koracoo leans her head back against the wall and looks at the roof. Tiny points of light sparkle. Holes. If it rains, by morning we will be drenched.

“Koracoo, what will we do if Atotarho does not release us in the morning? Have you considered that? It would be a great boon for him to capture War Chief Koracoo and her deputy.” I pause, watching her. “We

must

get back on the children’s trail as soon as poss—”

Abruptly, I’m on the trail, staring down at the wolf-chewed corpse of a young girl. Koracoo says, “She is not one of our children.”

The birds have pecked out her eyes and devoured most of the flesh of her face. Ropes of half-chewed intestines snake across the shells. The broken shaft of an arrow protrudes from her chest. A short distance away, an elaborately carved conch shell pendant rests. It is gorgeous. A False Face with a long bent nose, slanted mouth, and hollow eyes stare up from the shell.

I walk closer and search the area around the mangled corpse for any clues that might reveal her killer. We’ve been following sandal tracks, distinctive ones with a herringbone pattern. I bend down, pick up the shell pendant, and subtly tuck it into my belt pouch without Koracoo seeing me. I know she would not like this—I am disturbing the dead and risk ghost sickness—but I have the sense that this pendant—

I’m back in the prisoners’ house.

Warriors’ voices hiss. Feet shuffle, and shadows pass back and forth, blotting out the silver gleam that rims the door.

“Open the door,” Chief Atotarho orders.

Atotarho moves painfully, rocking and swaying as he enters the house with his lamp. He has seen fifty-two summers, and has braided rattlesnake skins into his gray-streaked black hair and pinned it into a bun at the back of his head. The style gives his narrow face a starved look. He was once, a long time ago, a great warrior. But now, his black cape covers a crooked and misshapen body. To the warriors, he says, “Close the door behind me.”

“But … my chief, you can’t go in alone. There are two of them. What if they attack you?”

“I will risk it. Close the door.”

As the door closes, the lamplight seems to grow brighter, reflecting from the plank walls like gigantic amber wings. Atotarho wears a beautiful black ritual cape covered with circlets of bone cut from human skulls. When the lamplight touches them, they wink. “War Chief Koracoo, Deputy Gonda, I must speak with you in confidence. Is that possible between us?”

Our people have been at war for decades. It is a fair question.

Koracoo rises to her feet. “You have my oath, Chief. Whatever we say here remains between us.”

I get up and stand beside her. “You have my oath, as well.”

Atotarho comes forward with great difficulty. “Forgive me, I cannot stand for long. I need to sit down.” He lowers himself to sit upon the cold dirt floor and places his oil lamp in front of him. “Please, join me.” He gestures to the floor, and I notice that his fingertips are tattooed with snake eyes, and he wears bracelets of human finger bones. “This will not be an easy conversation for any of us.”

We sit.

Koracoo asks, “What is it you wish to discuss?”

The old man doesn’t seem to hear. His gaze is locked on the lamp. The fragrance of walnut oil perfumes the air. Finally, he whispers, “Stories have been traveling the trails for several moons, but only I believed them. She has been gone for many summers—perhaps as long as twenty, though no one can be sure. She’s very cunning.”

Koracoo says, “Who?”

Atotarho bows his head. “Have you heard the name Gannajero?”

I feel like the earth has been kicked out from under me. More legend than human, hideous stories swirl about Gannajero. She is evil incarnate. A beast in the form of an old woman.

Koracoo softly answers, “Yes. I’ve heard of her.”

Atotarho flexes his crooked misshapen fingers. “Rumors say that she has returned to our country. Many villages are missing children. I have been … so afraid …” He rubs a hand over his face.

“That your daughter is with her?”

He seems to be trying to control his voice. “Yes. All day, every day, I pray to the gods to let my Zateri die if she is with Gannajero. I would prefer it. Anything would be b-better …”

Koracoo gives him a few moments to continue. When it’s clear he can’t, she says, “I understand.”

Atotarho’s mouth trembles. “No, I do not think you do. You are too young. When she was last here, you were not even a woman yet, were you?”

“I had seen only seven summers, but I recall hearing my family whisper about Gannajero, and it was with great dread.”

Atotarho extends his hands to the lamp as if to warm them. His knuckles resemble knotted twigs. “When I had seen five summers, my older brother and sister were captured in a raid. My sister was killed, but my brother was sold to an old man among the Flint People. I heard many summers later that my brother was utterly mad. His nightmares used to wake the entire village. Sometimes he screamed all night long. He eventually killed the old man, slit his throat, and ran away into the forest. No one ever saw him again.”

From some great distance, Sindak says,

“Towa, I swear, you’re a fool for continuing to be loyal to a chief you know you cannot trust.”

Then Koracoo says, “It would help me if you told me everything you know about Gannajero. Who is she? Where is she from? I know only old stories that make her sound more like a Spirit than a human being.”

Atotarho clasps his hands in his lap. “I don’t know much. No one does. They say she was born among the Flint or Hills People. Her grandmother was supposedly a clan elder, a powerful woman. But during a raid when Gannajero was eight, she was stolen and sold into slavery to the Mountain People. Then sold again, and again. She was apparently a violent child. Several times she was beaten almost to death by her owners.”

“And now she does the same thing to other children?” The hatred in my voice makes Atotarho and Koracoo turn. “What sort of men would help her? How does she find them?”

“I wish I knew. Twenty summers ago, we thought they were all outcasts, men who had no families or villages. Then we discovered one of her men among our own. He was my sister’s son, Jonil. A man of status and reputation. He’d been sending her information about planned raids, then capturing enemy children and selling them to her.”

I clench my fists. Warfare provides opportunities for greedy men that are not available in times of peace. Since many slaves are taken during attacks, it is easy to siphon off a few and sell them to men who no longer see them as human. War does that. It turns people—even children—into

things,

and gives men an opportunity to vent their rage and hatred in perverted ways that their home villages would never allow.

“Why? Why did he do it?”

Atotarho bows his head, and the shadows of his eyelashes darken his cheeks. “She rewards her servants well. When we searched Jonil’s place in the longhouse, we found unbelievable riches—exotic trade goods like obsidian and buffalo wool from the far west. Conch shells from the southern ocean. An entire basket of pounded copper sheets covered with strings of pearls and magnificently etched shell gorgets.”

Koracoo sits quietly for a time, thinking, before she says, “That means it will be difficult to buy the children back.”

“Virtually impossible. She profits enormously from her captives. With all the stealing and raiding going on, there are too many evil men with great wealth. But … if my daughter is being held captive with your children, I will give you whatever I have to get all of them back.”

Koracoo stares at him, judging the truthfulness of his words. Atotarho looks her straight in the eyes without blinking. Finally, Koracoo asks, “Why would you buy our children? We are your enemies.”

“If you are willing to risk your lives to save my daughter, you are not my enemy.”

The night has gone utterly quiet. The guards must be holding their breaths, listening. Very softly Koracoo says, “Why haven’t you already mounted a search party and sent them out with this same offer? Surely you can trust your own handpicked warriors more than you can us.”