The Cosmic Landscape (34 page)

It sounds like there are two different theories of hadrons—QCD and String Theory. But it was understood, almost from the beginnings of String Theory, that these two kinds of theories might really be two faces of the same theory. In fact the key insight preceded the discovery of QCD by a couple of years.

The bridge between ordinary Feynman diagrams and String Theory became clear when I received a letter in 1970 from Denmark. Holger Bech Nielsen was very enthusiastic about my paper on rubber band theory, and he wanted to share some of his ideas with me. He explained in his letter how he, too, had been thinking about something very similar to elastic strings, but he had a different angle on it.

At about that time, Dick Feynman was arguing that a lot of what was known about hadrons indicated that they were made up of smaller, more fundamental, objects of some sort. He wasn’t very specific about what these objects were. He just called them

partons

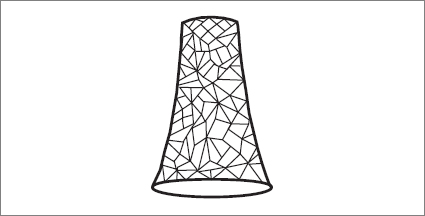

to indicate that they were the parts that made up hadrons. The idea of combining String Theory with Feynman’s parton ideas was something I had been thinking about for quite a while. Nielsen had thought deeply about this and had an extremely interesting vision. He suggested that the smooth, continuous world sheet is really a network or mesh of closely spaced lines and vertices. In other words it is a very complicated, but otherwise ordinary, Feynman diagram composed of a great many propagators and vertices. The mesh becomes finer and finer as more and more propagators and vertices are added. And it becomes better and better approximated by a smooth sheet. The String Theory of hadrons can be pictured in just this way. The world sheets, tubes, and Y-joints are really just very complicated Feynman diagrams involving quarks and a very large number of gluons. When you look at the world sheet from a distance, it appears smooth. But under a microscope it looks like a “fishnet” or “basketball-net” Feynman diagram.

3

The lines in the fishnet represent the propagators of point particles, Feynman’s partons or Gell-Mann’s quarks and gluons. But the “fabric” created by these microscopic world lines forms a smooth, almost continuous world sheet.

As I said earlier, you can picture a string as a bunch of partons, strung together like a pearl necklace. Feynman’s parton theory, Gell-Mann’s quark theory, and rubber band theory are all different facets of QCD.

The string or rubber band model of hadrons was not an immediate success. Many theoretical physicists working on hadron physics in the 1960s had a very negative attitude toward any theory that attempted to visualize the phenomenon. As noted, the zealous advocates of the S-matrix theory maintained that the collision is an unknowable black box, a perverse view held with almost messianic fervor. They had only one commandment: “Thou shalt not leave the mass shell.” That is, don’t look inside the collision to discover the mechanisms taking place. Don’t try to understand the composition of particles like the proton. Hostility to the idea that the Veneziano formula represented scattering of two rubber bands persisted, to some extent, until one day when Murray Gell-Mann put his stamp of approval on it.

Murray was the king of physics when I first met him in Coral Gables, Florida, in 1970. At that time the high point of the theoretical physicists’ season of conferences was the Coral Gables conference. And the high point of the conference was Murray’s lecture. The 1970 event was the first big conference I had ever been invited to—not to lecture, of course, but to be part of the audience. Murray gave his talk on the subject of

spontaneously broken dilatation symmetry,

one of his less successful efforts. I can barely recall the lecture, but I remember very well what transpired afterward. Murray and I got stuck in an elevator together.

I was a totally unknown physicist at the time, and the physics community was in awe of Murray. Needless to say, getting stuck with him excited all my insecurities.

Needing to make conversation, Murray asked what I did. Intimidated, I responded, “I’m working on a theory of hadrons that represents them as some kind of elastic string, like a rubber band.” In the unforgettable awful moment that followed, he started to laugh. Not a little chuckle—a big guffaw. I felt like a worm. Then the elevator door opened, and I slunk out with burning ears.

I didn’t see Murray again for about two years. Our next meeting was at another conference that took place at Fermilab, a big particle accelerator in Illinois. The Fermilab conference was a really big deal: about one thousand people participated, including the most influential theoretical and experimental high-energy physicists in the world. Once again I was a spectator.

At the very beginning of the conference, before the first lecture, I was standing with a group of friends, and Murray came sauntering over. In front of all these people, he said, “I’m sorry I laughed at you in the elevator that day. I think the work that you are doing is fantastic, and I’m going to spend most of my big lecture talking about it. Let’s sit down and talk about it when we get a chance.” I went from feeling like a worm to feeling like a prince. The king was going to confer royalty on me!

After that for a couple of days, I chased Murray, asking, “Is this a good time, Murray?” Each time his answer was, “No, I have to talk to someone important.”

On the last day of the conference, there was a long waiting line to talk to a travel agent. I needed help changing my air tickets, and I had waited about an hour on the line. Finally I was only two or three people from the travel agent when Murray came over and plucked me out, saying, “Now! Let’s talk now. I have fifteen minutes.” Okay, I said to myself, this is it. Do it right and you’re a prince. Do it wrong, and you’re fish bait.

We sat down at an empty table, and I started to explain how the new rubber band theory was related to his and Feynman’s ideas. I wanted to explain the fishnet-diagram idea. I remember saying, “I’ll begin explaining it in terms of partons.”

“Partons? Partons? What the hell is a parton? Put-ons? You’re putting me on, right?” I knew I had made a bad mistake, but I didn’t know exactly how. I tried to explain, but all I got back was, “Put-on? What is that?” Fourteen of my precious fifteen minutes were gone by the time he said, “These put-ons, do they have charge?” I answered yes. “Do they have SU(3)?” Again I agreed. Then all became clear. He said, slowly, “Oooh, you mean quarks!” I had committed the unpardonable sin of calling the constituents by Feynman’s word instead of Murray’s. It seems I was the only person in the world who didn’t know about the weird rivalry between the two great Caltech physicists.

Anyway, I had one or two minutes to spill out what I was thinking, and then Murray looked at his watch, “Okay, thanks. Now I have someone

important

to talk to before my lecture.”

So close and yet so far. No royal treatment for me: just dirt and mud. And then the next thing I heard was Murray holding forth. He was telling a group of his cronies everything I had told him. “Susskind says this, and Susskind says that. We have to learn Susskind’s String Theory.” And then Murray gave his big talk, the last of the conference if I recall correctly. Although String Theory was only a small part of the lecture, it had received Murray’s blessing. The whole thing was quite a roller-coaster ride.

Although Murray did not work on String Theory, his mind was open to new ideas, and he played a significant role in encouraging others. With no question, he was one of the first to recognize String Theory’s potential importance both as a theory of hadrons and later as a theory of Planck-scale phenomena.

String Theory comes in many versions. The versions that we knew about in the early seventies were mathematically very precise—too precise. Although it is absolutely clear from the modern vantage point that hadrons are strings, the theory would have to be modified several ways before it could describe real baryons and mesons.

Three huge problems plagued the original String Theories. One was so bizarre that conservative physicists, particularly the S-matrix enthusiasts, found it a source of humor. It was the problem of too many dimensions. String Theory, like all physical theories, takes place in space and time. Before Einstein, space and time were two separate things; but under the influence of Minkowski, the two merged into space-time, the four-dimensional world in which every event has a location in space and a moment in time. Einstein and Minkowski turned time into the “fourth dimension.” But time and space are not entirely similar. Even though the Theory of Relativity sometimes mixes space and time in various mathematical transformations, time and space are different. They “feel” different. For this reason, instead of describing space-time as being four-dimensional, we say it is three-plus-one-dimensional to indicate that there are three dimensions of space and one of time. Is it possible to have more dimensions of space? Yes, that’s commonplace in mod-ern physics. It’s not too hard to imagine moving around in more, or for that matter fewer, than three dimensions. Edwin Abbott’s famous nineteenth-century book

Flatland

describes life in a world of only two dimensions of space. But a world with more (or fewer) than one time dimension is incomprehensible. It doesn’t seem to make any sense. So, for the most part, when physicists want to play with the number of dimensions of space-time, they work with 3+1, 4+1, 5+1, or any number of space dimensions, but with only one time dimension.

Physicists have always hoped that someday they would be able to explain why space has three dimensions and not two or seven or eighty-four. So, in theory, string theorists should have been delighted to discover that their mathematics works out consistently only in a very particular number of dimensions. The trouble was that the number was 9+1 dimensions, not 3+1. Something very subtle goes wrong with the mathematics unless the number of space dimensions is nine—three times as many space dimensions as the world we actually live in! It seemed the joke was on string theorists.

As a physics teacher, I hate to tell students something important and then say I can’t explain it. It’s too advanced. Or it’s too technical. I spend a lot of time figuring out how to explain difficult things in elementary terms. One of my biggest frustrations is that I have never succeeded in finding an elementary explanation of why String Theory is happy only if the number of dimensions is 9+1. Nor has anyone else. What I will tell you is that it has to do with the violent jittery quantum motion of a string. These quantum fluctuations can pile up and get completely out of control unless some very delicate conditions are met. And those conditions are met only in 9+1 dimensions.

Being off by a factor of three in cosmology was not so bad in those days, but it was very bad in particle physics. Particle physicists were used to high accuracy in their numbers. There is no number that they were more confident of than the number of dimensions of space. No amount of experimental uncertainty could explain the loss of six dimensions. It was a debacle. Space-time, then and now, is 3+1-dimensional with no uncertainty.

Being wrong about the dimensionality of space was bad enough, but to compound the problem, the nuclear force law between hadrons came out all wrong. Instead of producing the kind of short-range forces that exist between particles in the nucleus, String Theory gave rise to long-range forces, which looked, for all the world, almost exactly like electric and gravitational forces. If the nuclear short-range force was adjusted to be the right strength, the electric force would be about one hundred times too strong, and the gravitational force would be too strong by a stupendous factor—about 10

40

. Identifying these long-range forces with the real gravitational and electric forces was out of the question, but only if one wanted to use the same strings to describe hadrons.

All forces in nature—be they gravitational, electric, or nuclear—have the same origin. Think of an electron circling a central nucleus. From time to time it emits a photon, and where does the photon go? If the atom is excited, the photon can escape while the electron jumps to a lower-energy orbit. But if the atom is already in its lowest-energy state, the photon cannot carry off any energy. The only alternative for the photon is to be absorbed, either by another electron or by the charged nucleus. Thus, in a real atom, the electrons and nucleus are constantly tossing photons back and forth in a kind of atomic juggling act. This “exchange” of particles, in this case the photon, is the source of all forces in nature. Force—whether it is electric, magnetic, gravitational, or any other—ultimately traces back to Feynman “exchange diagrams,” in which quanta hop from one particle to another. For the electric and magnetic force, photons are the exchanged quanta; for the gravitational forces the graviton does the job. You and I are kept anchored to the earth by gravitons jumping between earth and our bodies. But for the forces binding protons and neutrons into nuclei, the exchanged objects are pions. If one goes deeper into the protons and neutrons, quarks are found tossing gluons between them. This connection between force and exchanged “messenger” particles was one of the great themes of twentieth-century physics.