The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (25 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

S:

You mean you just end up on the other side of the pain?

TR:

Yes, [on the other side of] the creator of the pain, which is confusion.

Student:

It seems that both Christ and Padmasambhava had to use magic in order to achieve their final victory.

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Not necessarily. It might have become magic by itself.

S:

I mean the lake and sitting in the lotus flower and—

TR:

That was not magic particularly. That was just what happened. And for that matter, the resurrection could be said not to have been magic at all. It’s just what happened in the case of Christ.

S:

It’s magical in the sense that it’s very unusual. I mean, if that isn’t magic, what is?

TR:

Well, in that case, what we’re doing here is magic. We are doing something extremely unusual for America. It happens to have developed by itself. We couldn’t have created the whole situation. Our getting together and discussing this subject just happened by itself.

Student:

Rinpoche, what you were saying about using pain as an adornment seemed to me like the difference between collecting information and really experiencing the implications of it. But I don’t see how you can be sure that you are really making contact with your experience.

Trungpa Rinpoche:

One shouldn’t regard the whole thing as a way of getting ahead of ego. Just relate to it as an ongoing process. Don’t do anything with it, just go on. It’s a very casual matter.

Student:

What does Loden Choksi mean?

Trungpa Rinpoche: Loden

means “possessing intelligence”;

choksi

means “supreme world” or “supreme existence.” In this case, the name does not seem to be as significant as with some of the other aspects. It is not nearly as vivid as, for example, Senge Dradrok or Dorje Trolö. Loden Choksi has something to do with being skillful.

Student:

What is the difference between the kind of direct intellectual perception you were talking about here and other kinds of perception?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

It seems that if you are purely looking for answers, then you don’t perceive anything. In the proper use of intellect, you don’t look for answers, you just see; you just take notes in your mind. And even then, you don’t have the goal of collecting information; you just relate to what is there as an expression of intelligence. That way, your intelligence can’t be conned by extraneous suggestions. Rather, you have sharpened your intellect and you can relate directly to what is happening.

S:

But how would you differentiate that from other kinds of perception?

TR:

In general, we have perceptions with all kinds of things mixed in; that is, we have conditioned perceptions which contain a purpose of magnetizing or destroying. Such perceptions contain passion and aggression and all the rest of it. There are ulterior motives of all kinds, as opposed to just seeing clearly, just looking at things very precisely, sharply.

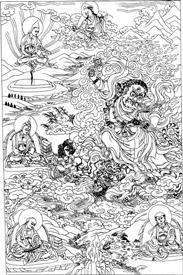

Dorje Trolö.

SEVEN

Dorje Trolö and the Three Styles of Transmission

T

HE EIGHTH ASPECT

of Padmasambhava is Dorje Trolö, the final and absolute aspect of crazy wisdom. To discuss this eighth aspect of Padmasambhava, we have to have some background knowledge about [traditional] ways of communicating the teachings. The idea of lineage is associated with the transmission of the message of

adhishthana,

which means “energy” or, if you like, “grace.” This is transmitted like an electric current from the trikaya guru to sentient beings. In other words, crazy wisdom is a continual energy that flows and that, as it flows, regenerates itself. The only way to regenerate this energy is by radiating or communicating it, by putting it into practice or acting it out. It is unlike other energies, which, when you use them, move toward cessation or extinction. The energy of crazy wisdom regenerates itself through the process of our living it. As you live this energy, it regenerates itself; you don’t live for death, but you live for birth. Living is a constant birth process rather than a wearing-out process.

The lineage has three styles of transmitting this energy. The first is called the

kangsaknyen gyü.

Here, the energy of the lineage is transmitted by word of mouth using ideas and concepts. In some sense, this is a crude or primitive method, a somewhat dualistic approach. However, in this case, the dualistic approach is functional and worthwhile.

If you sit cross-legged as if you were meditating, the chances are you might actually find yourself meditating after a while. This is like achieving sanity by pushing yourself to imitate it, by behaving as though you were sane already. In the same way, it is possible to use words, terms, images, and ideas—teaching orally or in writing—as though they were an absolutely perfect means of transmission. The procedure is to present an idea, then the refutation of [the opposite of] that idea, and then to associate the idea with an authentic scripture or teaching that has been given in the past.

Believing in the sacredness of certain things on a primitive level is the first step in transmission. Traditionally, scriptures or holy books are not to be trodden upon, sat upon, or otherwise mistreated, because very powerful things are said in them. The idea is that by mistreating the books, you mistreat the messages they contain. This is a way of believing in some kind of entity, or energy, or force—in the living quality of something.

The second style of communicating, or teaching, is the

rigdzin da gyü.

This is the method of crazy wisdom, but on the relative level, not the absolute level. Here you communicate by creating incidents that seem to happen by themselves. Such incidents are seemingly blameless, but they do have an instigator somewhere. In other words, the guru tunes himself in to the cosmic energy, or whatever you would like to call it. Then if there is a need to create chaos, he directs his attention toward chaos. And quite appropriately, chaos presents itself, as if it happened by accident or mistake.

Da

in Tibetan means “symbol” or “sign.” The sense of this is that the crazy-wisdom guru does not speak or teach on the ordinary level, but rather, he or she creates a symbol, or means. A symbol in this case is not like something that stands for something else, but it is something that presents the living quality of life and creates a message out of it.

The third one is called

gyalwa gong gyü. Gong gyü

means “thought lineage” or “mind lineage.” From the point of view of the thought lineage, even the method of creating situations is crude or primitive. Here, a mutual understanding takes place that creates a general atmosphere—and the message is understood. If the guru of crazy wisdom is an authentic being, then the authentic communication happens, and the means of communication is neither words nor symbols. Rather, just by being, a sense of precision is communicated. Maybe it takes the form of waiting—for nothing. Maybe it takes pretending to meditate together but not doing anything. For that matter, it might involve having a very casual relationship; discussing the weather and the flavor of tea; how to make curry, chop suey, or macrobiotic cuisine; or talking about history or the history of the neighbors—whatever.

The crazy wisdom of the thought lineage takes a form that is somewhat disappointing to the eager recipient of the teachings. You might go and pay a visit to the guru, which you have especially prepared for, and he isn’t even interested in talking to you. He’s busy reading the newspaper. Or for that matter, he might create “black air,” a certain intensity that makes the whole environment threatening. And there’s nothing happening—nothing happening to such an extent that you walk out with a sense of relief, glad you didn’t have to be there any longer. But then something happens to you as if everything did happen during those periods of silence or intensity.

The thought lineage is more of a presence than something happening. Also, it has an extraordinarily ordinary quality.

In traditional abhishekas, or initiation ceremonies, the energy of the thought lineage is transmitted into your system at the level of the fourth abhisheka. At that point, the guru will ask you suddenly, “What is your name?” or “Where is your mind?” This abrupt question momentarily cuts through your subconscious gossip, creating a bewilderment of a different type [from the type already going on in you mind]. You search for an answer and realize you do have a name and he wants to know it. It is as if you were nameless before but have now discovered that you have a name. It is that kind of an abrupt moment.

Of course, such ceremonies are subject to corruption. If the teacher is purely following the scriptures and commentaries, and the student is eagerly expecting something powerful, then both the teacher and the student miss the boat simultaneously.

Thought-lineage communication is the teaching of the dharmakaya; the communication by signs and symbols—creating situations—is the sambhogakaya level of teaching; and the communication by words is the nirmanakaya level of teaching. Those are the three styles in which the crazy-wisdom guru communicates to the potential crazy-wisdom student.

The whole thing is not as outrageous as it may seem. Nevertheless, there is an undercurrent of taking advantage of the mischievousness of reality, and this creates a sense of craziness or a sense that something or other is not too solid. Your sense of security is under attack. So the recipient of crazy wisdom—the ideal crazy-wisdom student—should feel extremely insecure, threatened. That way, you manufacture half of the crazy wisdom and the guru manufacturers the other half. Both the guru and the student are alarmed by the situation. Your mind has nothing to work on. A sudden gap has been created—bewilderment.

This kind of bewilderment is quite different from the bewilderment of ignorance. This is the bewilderment that happens between the question and the answer. It is the boundary between the question and the answer. There is a question, and you are just about to answer that question: there is a gap. You have oozed out your question, and the answer hasn’t come through yet. There is already a feeling of a sense of the answer, a sense that something positive is happening—but nothing has happened yet. There is that point where the answer is just about to be born and the question has just died.

There is very strange chemistry there; the combination of the death of the question and the birth of the answer creates uncertainty. It is intelligent uncertainty—sharp, inquisitive. This is unlike ego’s bewilderment of ignorance, which has totally and completely lost touch with reality because you have given birth to duality and are uncertain about how to handle the next step. You are bewildered because of ego’s approach of duality. But, in this case, it is not bewilderment in the sense of not knowing what to do, but bewilderment because something is just about to happen and hasn’t happened yet.

The crazy wisdom of Dorje Trolö is not reasonable but somewhat heavy-handed, because wisdom does not permit compromise. If you compromise between black and white, you come out with a gray color—not quite white and not quite black. It is a sad medium rather than a happy medium—disappointing. You feel sorry that you’ve let it be compromised. You feel totally wretched that you have compromised. That is why crazy wisdom does not know any compromise. The style of crazy wisdom is to build you up: build up your ego to the level of absurdity, to the point of comedy, to a point that is bizarre—and then suddenly let you go. So you have a big fall, like Humpty Dumpty: “All the king’s horses and all the king’s men/Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again.”

To get back to the story of Padmasambhava as Dorje Trolö, he was asked by a local deity in Tibet, “What frightens you the most?” Padmasambhava said, “I’m frightened of neurotic sin.” It so happens that the Tibetan word for “sin”—

dikpa

—is also the word for “scorpion,” so the local deity thought he could frighten Padmasambhava by manifesting himself as a giant scorpion. The local deity was reduced to dust—as a scorpion.

Tibet is supposedly ringed by snow-capped mountains, and there are twelve goddesses associated with those mountains who are guardians of the country. When Dorje Trolö came to Tibet, one of those goddesses refused to surrender to him. She ran away from him—she ran all over the place. She ran up a mountain thinking she was running away from Padmasambhava and found him already there ahead of her, dancing on the mountaintop. She ran away down a valley and found Padmasambhava already at the bottom, sitting at the confluence of that valley and the neighboring one. No matter where she ran, she couldn’t get away. Finally, she decided to jump into a lake and hide there. Padmasambhava turned the lake into boiling iron, and she emerged as a kind of skeleton being. Finally, she had to surrender because Padmasambhava was everywhere. It was extremely claustrophobic in some way.

One of the expressions of crazy wisdom is that you can’t get away from it. It’s everywhere (whatever “it” is).