The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (11 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

By meditation here we mean something very basic and simple that is not tied to any one culture. We are talking about a very basic act: sitting on the ground, assuming a good posture, and developing a sense of our spot, our place on this earth. This is the means of rediscovering ourselves and our basic goodness, the means to tune ourselves in to genuine reality, without any expectations or preconceptions.

The word

meditation

is sometimes used to mean contemplating a particular theme or object: meditating

on

such and such a thing. By meditating on a question or problem, we can find the solution to it. Sometimes meditation also is connected with achieving a higher state of mind by entering into a trance or absorption state of some kind. But here we are talking about a completely different concept of meditation: unconditional meditation, without any object or idea in mind. In the Shambhala tradition meditation is simply training our state of being so that our mind and body can be synchronized. Through the practice of meditation, we can learn to be without deception, to be fully genuine and alive.

Our life is an endless journey; it is like a broad highway that extends infinitely into the distance. The practice of meditation provides a vehicle to travel on that road. Our journey consists of constant ups and downs, hope and fear, but it is a good journey. The practice of meditation allows us to experience all the textures of the roadway, which is what the journey is all about. Through the practice of meditation, we begin to find that within ourselves there is no fundamental complaint about anything or anyone at all.

Meditation practice begins by sitting down and assuming your seat cross-legged on the ground. You begin to feel that by simply being on the spot, your life can become workable and even wonderful. You realize that you are capable of sitting like a king or queen on a throne. The regalness of that situation shows you the dignity that comes from being still and simple.

In the practice of meditation, an upright posture is extremely important. Having an upright back is not an artificial posture. It is natural to the human body. When you slouch, that is unusual. You can’t breathe properly when you slouch, and slouching also is a sign of giving in to neurosis. So when you sit erect, you are proclaiming to yourself and to the rest of the world that you are going to be a warrior, a fully human being.

To have a straight back you do not have to strain yourself by pulling up your shoulders; the uprightness comes naturally from sitting simply but proudly on the ground or on your meditation cushion. Then, because your back is upright, you feel no trace of shyness or embarrassment, so you do not hold your head down. You are not bending to anything. Because of that, your shoulders become straight automatically, so you develop a good sense of head and shoulders. Then you can allow your legs to rest naturally in a cross-legged position; your knees do not have to touch the ground. You complete your posture by placing your hands lightly, palms down, on your thighs. This provides a further sense of assuming your spot properly.

In that posture, you don’t just gaze randomly around. You have a sense that you are

there

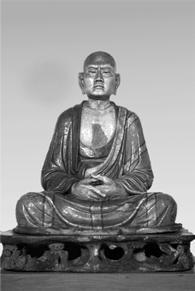

properly; therefore your eyes are open, but your gaze is directed slightly downward, maybe six feet in front of you. In that way, your vision does not wander here and there, but you have a further sense of deliberateness and definiteness. You can see this royal pose in some Egyptian and South American sculptures, as well as in Oriental statues. It is a universal posture, not limited to one culture or time.

I-chou Lohan. This statue shows one of the disciples of the Buddha in the posture of meditation

.

PHOTO BY ROBERT NEWMAN. FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

In your daily life, you should also be aware of your posture, your head and shoulders, how you walk, and how you look at people. Even when you are not meditating, you can maintain a dignified state of existence. You can transcend your embarrassment and take pride in being a human being. Such pride is acceptable and good.

Then, in meditation practice, as you sit with a good posture, you pay attention to your breath. When you breathe, you are utterly there, properly there. You go out with the out-breath, your breath dissolves, and then the in-breath happens naturally. Then you go out again. So there is a constant going out with the out-breath. As you breathe out, you dissolve, you diffuse. Then your in-breath occurs naturally; you don’t have to follow it in. You simply come back to your posture, and you are ready for another out-breath. Go out and dissolve:

tshoo;

then come back to your posture; then

tshoo,

and come back to your posture.

Then there will be an inevitable

bing!

—thought. At that point, you say, “thinking.” You don’t say it out loud; you say it mentally: “thinking.” Labeling your thoughts gives you tremendous leverage to come back to your breath. When one thought takes you away completely from what you are actually doing—when you do not even realize that you are on the cushion, but in your mind you are in San Francisco or New York City—you say “thinking,” and you bring yourself back to the breath.

It doesn’t really matter what thoughts you have. In the sitting practice of meditation, whether you have monstrous thoughts or benevolent thoughts, all of them are regarded purely as thinking. They are neither virtuous nor sinful. You might have a thought of assassinating your father or you might want to make lemonade and eat cookies. Please don’t be shocked by your thoughts: Any thought is just thinking. No thought deserves a gold medal or a reprimand. Just label your thoughts “thinking,” then go back to your breath. “Thinking,” back to the breath; “thinking,” back to the breath.

The practice of meditation is very precise. It has to be on the dot, right on the dot. It is quite hard work, but if you remember the importance of your posture, that will allow you to synchronize your mind and body. If you don’t have good posture, your practice will be like a lame horse trying to pull a cart. It will never work. So first you sit down and assume your posture, then you work with your breath;

tshoo,

go out, come back to your posture;

tshoo,

come back to your posture;

tshoo

. When thoughts arise, you label them “thinking” and come back to your posture, back to your breath. You have mind working with breath, but you always maintain body as a reference point. You are not working with your mind alone. You are working with your mind and your body, and when the two work together, you never leave reality.

The ideal state of tranquillity comes from experiencing body and mind being synchronized. If body and mind are unsynchronized, then your body will slump—and your mind will be somewhere else. It is like a badly made drum: The skin doesn’t fit the frame of the drum; so either the frame breaks or the skin breaks, and there is no constant tautness. When mind and body are synchronized, then, because of your good posture, your breathing happens naturally; and because your breathing and your posture work together, your mind has a reference point to check back to. Therefore your mind will go out naturally with the breath.

This method of synchronizing your mind and body is training you to be very simple and to feel that you are not special, but ordinary, extraordinary. You sit simply, as a warrior, and out of that, a sense of individual dignity arises. You are sitting on the earth and you realize that this earth deserves you and you deserve this earth. You are there—fully, personally, genuinely. So meditation practice in the Shambhala tradition is designed to educate people to be honest and genuine, true to themselves.

In some sense, we should regard ourselves as being burdened: We have the burden of helping this world. We cannot forget this responsibility to others. But if we take our burden as a delight, we can actually liberate this world. The way to begin is with ourselves. From being open and honest with ourselves, we can also learn to be open with others. So we can work with the rest of the world, on the basis of the goodness we discover in ourselves. Therefore, meditation practice is regarded as a good and in fact excellent way to overcome warfare in the world: our own warfare as well as greater warfare.

THREE

The Genuine Heart of Sadness

Through the practice of sitting still and following your breath as it goes out and dissolves, you are connecting with your heart. By simply letting yourself be, as you are, you develop genuine sympathy toward yourself.

I

MAGINE THAT YOU ARE

sitting naked on the ground, with your bare bottom touching the earth. Since you are not wearing a scarf or hat, you are also exposed to heaven above. You are sandwiched between heaven and earth: a naked man or woman, sitting between heaven and earth.

Earth is always earth. The earth will let anyone sit on it, and earth never gives way. It never lets you go—you don’t drop off this earth and go flying through outer space. Likewise, sky is always sky; heaven is always heaven above you. Whether it is snowing or raining or the sun is shining, whether it is daytime or nighttime, the sky is always there. In that sense, we know that heaven and earth are trustworthy.

The logic of basic goodness is very similar. When we speak of basic goodness, we are not talking about having allegiance to good and rejecting bad. Basic goodness is good because it is unconditional, or fundamental. It is there already, in the same way that heaven and earth are there already. We don’t reject our atmosphere. We don’t reject the sun and the moon, the clouds and the sky. We accept them. We accept that the sky is blue; we accept the landscape and the sea. We accept highways and buildings and cities. Basic goodness is that basic, that unconditional. It is not a “for” or “against” view, in the same way that sunlight is not “for” or “against.”

The natural law and order of this world is not “for” or “against.” Fundamentally, there is nothing that either threatens us or promotes our point of view. The four seasons occur free from anyone’s demand or vote. Hope and fear cannot alter the seasons. There is day; there is night. There is darkness at night and light during the day, and no one has to turn a switch on and off. There is a natural law and order that allows us to survive and that is basically good, good in that it is there and it works and it is efficient.

We often take for granted this basic law and order in the universe, but we should think twice. We should appreciate what we have. Without it, we would be in a total predicament. If we didn’t have sunlight, we wouldn’t have any vegetation, we wouldn’t have any crops, and we couldn’t cook a meal. So basic goodness is good

because

it is so basic, so fundamental. It is natural and it works, and therefore it is good, rather than being good as opposed to bad.

The same principle applies to our makeup as human beings. We have passion, aggression, and ignorance. That is, we cultivate our friends and we ward off our enemies and we are occasionally indifferent. Those tendencies are not regarded as shortcomings. They are part of the natural elegance and equipment of human beings. We are equipped with nails and teeth to defend ourselves against attack, we are equipped with a mouth and genitals to relate with others, and we are lucky enough to have complete digestive and respiratory systems so that we can process what we take in and flush it out. Human existence is a natural situation, and like the law and order of the world, it is workable and efficient. In fact, it is wonderful, it is ideal.

Some people might say this world is the work of a divine principle, but the Shambhala teachings are not concerned with divine origins. The point of warriorship is to work personally with our situation now, as it is. From the Shambhala point of view, when we say that human beings are basically good, we mean that they have every faculty they need, so that they don’t have to fight with their world. Our being is good because it is not a fundamental source of aggression or complaint. We cannot complain that we have eyes, ears, a nose, and a mouth. We cannot redesign our physiological system, and for that matter, we cannot redesign our state of mind. Basic goodness is what we have, what we are provided with. It is the natural situation that we have inherited from birth onward.

We should feel that it is wonderful to be in this world. How wonderful it is to see red and yellow, blue and green, purple and black! All of these colors are provided for us. We feel hot and cold; we taste sweet and sour. We have these sensations, and we deserve them. They are good.

So the first step in realizing basic goodness is to appreciate what we have. But then we should look further and more precisely at what we are, where we are, who we are, when we are, and how we are as human beings, so that we can take possession of our basic goodness. It is not really a possession, but nonetheless, we deserve it.

Basic goodness is very closely connected to the idea of

bodhichitta

in the Buddhist tradition.

Bodhi

means “awake” or “wakeful” and

chitta

means “heart,” so

bodhichitta

is “awakened heart.” Such awakened heart comes from being willing to face your state of mind. That may seem like a great demand, but it is necessary. You should examine yourself and ask how many times you have tried to connect with your heart, fully and truly. How often have you turned away, because you feared you might discover something terrible about yourself? How often have you been willing to look at your face in the mirror, without being embarrassed? How many times have you tried to shield yourself by reading the newspaper, watching television, or just spacing out? That is the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question: How much have you connected with yourself at all in your whole life?