The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (9 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The curriculum used in Shambhala Training was of great help in organizing the material for this book, and thanks are due to those who have worked with the author to develop and revise this curriculum over the past six years: Mr. David Rome, private secretary to the author and the assistant to the publisher at Schocken Books; Dr. Jeremy Hayward, vice president of the Nalanda Foundation; Mrs. Lila Rich, executive director of Shambhala Training; as well as the staff of Shambhala Training, notably Mr. Frank Berliner, Mrs. Christie Baker, and Mr. Dan Holmes.

Ongoing guidance was provided by Ösel Tendzin, the cofounder of Shambhala Training and Chögyam Trungpa’s dharma heir, who reviewed the original proposal for the book and gave critical feedback on the manuscript at various stages of completion. We are extremely grateful for his participation in this project.

A similar role was played by Mr. Samuel Bercholz, the publisher of Shambhala Publications. As shown by the name he gave to his company in 1968, Mr. Bercholz has a deeply rooted connection to Shambhala and its wisdom. His belief in this project and his constant interest in it were a major force in moving the manuscript along and bringing it to completion.

Two of the editors at Vajradhatu deserve special mention for their excellent work on the manuscript: Mrs. Sarah Levy and Mrs. Donna Holm. In addition, we would like to offer particular thanks to Mr. Ken Wilber, the author of

Up from Eden

and other books. Mr. Wilber read the manuscript in both penultimate and final form, and his detailed and pointed comments led to significant changes in the final text.

Mr. Robert Walker served as the administrative assistant to the editors, and without the secretarial and support services that he provided, this book never could have been completed. His excellent and diligent contribution to the project deserves our greatest thanks. Mrs. Rachel Anderson also served as an administrative assistant for a period of several months, and we thank her for her dedicated help. It is not possible to mention by name the many volunteers who produced the transcriptions that already existed when we began work on the book, but their efforts are gratefully acknowledged.

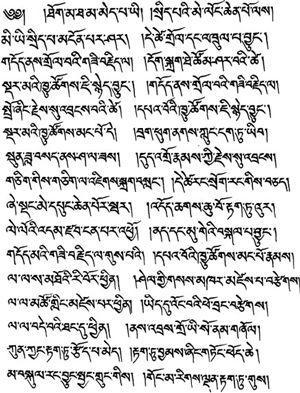

The editors also wish to thank the Nālandā Translation Group for the translations from the Tibetan that appear here, in particular Mr. Ugyen Shenpen, who calligraphed the original Tibetan writings. We also thank the editorial and production staff at Shambhala Publications for their assistance, notably Mr. Larry Mermelstein, Ms. Emily Hilburn, and Mrs. Hazel Bercholz.

We thank as well the many other readers who took time to review and comment on the final manuscript: Mr. Marvin Casper, Mr. Michael Chender, Lodrö Dorje, Dr. Larry Dossey, Dr. Wendy Goble, Dr. James Green, Miss Lynn Hildebrand, Miss Lynn Milot, Ms. Susan Purdy, Mr. Eric Skjei, Mrs. Susan Niemack Skjei, Mr. Joseph Spieler, Mr. Jeff Stone, and Mr. Joshua Zim. We particularly thank Dr. Goble for her careful copyediting of the text.

The blocks of calligraphic script that appear in this book are from a text of Shambhala. The excerpts and their translation are included in the copyright of this book.

It is impossible to express adequate thanks to the author—both for his vision in presenting the Shambhala teachings and for the privilege of assisting him with the editing of this book. In addition to working closely with the editors on the manuscript, he seemed able to provide an atmosphere of magic and power that pervaded and inspired this project. This is a somewhat outrageous thing to say, but once having read this book, perhaps the reader will find it not so strange a statement. It felt as though the author empowered this text so that it could rise above the poor vision of its editors and proclaim its wisdom. We hope only that we have not obstructed or weakened the power of these teachings. May they help to liberate all beings from the warring evils of the setting sun.

C

AROLYN

R

OSE

G

IMIAN

Boulder, Colorado

October 1983

Foreword

I

AM SO DELIGHTED

to be able to present the vision of Shambhala in this book. It is what the world needs and what the world is starved for. I would like to make it clear, however, that this book does not reveal any of the secrets from the Buddhist tantric tradition of Shambhala teachings, nor does it present the philosophy of the Kalacakra. Rather, this book is a manual for people who have lost the principles of sacredness, dignity, and warriorship in their lives. It is based particularly on the principles of warriorship as they were embodied in the ancient civilizations of India, Tibet, China, Japan, and Korea. This book shows how to refine one’s way of life and how to propagate the true meaning of warriorship. It is inspired by the example and the wisdom of the great Tibetan king, Gesar of Ling—his inscrutability and fearlessness and the way in which he conquered barbarianism by using the principles of Tiger, Lion, Garuda, Dragon (Tak, Seng, Khyung, Druk), which are discussed in this book as the four dignities.

I am honoured and grateful that in the past I have been able to present the wisdom and dignity of human life within the context of the religious teachings of Buddhism. Now it gives me tremendous joy to present the principles of Shambhala warriorship and to show how we can conduct our lives as warriors with fearlessness and rejoicing, without destroying one another. In this way, the vision of the Great Eastern Sun (Sharchen Nyima) can be promoted, and the goodness in everyone’s heart can be realised without doubt.

D

ORJE

D

RADÜL OF

M

UKPO

Boulder, Colorado

August 1983

Part One

HOW TO BE A WARRIOR

From the great cosmic mirror

Without beginning and without end,

Human society became manifest.

At that time liberation and confusion arose.

When fear and doubt occurred

Toward the confidence which is primordially free,

Countless multitudes of cowards arose.

When the confidence which is primordially free

Was followed and delighted in,

Countless multitudes of warriors arose.

Those countless multitudes of cowards

Hid themselves in caves and jungles.

They killed their brothers and sisters and ate their flesh,

They followed the example of beasts,

They provoked terror in each other;

Thus they took their own lives.

They kindled a great fire of hatred,

They constantly roiled the river of lust,

They wallowed in the mud of laziness:

The age of famine and plague arose.

Of those who were dedicated to the primordial confidence,

The many hosts of warriors,

Some went to highland mountains

And erected beautiful castles of crystal.

Some went to the lands of beautiful lakes and islands

And erected lovely palaces.

Some went to the pleasant plains

And sowed fields of barley, rice, and wheat.

They were always without quarrel,

Ever loving and very generous.

Without encouragement, through their self-existing inscrutability,

They were always devoted to the Imperial Rigden.

ONE

Creating an Enlightened Society

The Shambhala teachings are founded on the premise that there is basic human wisdom that can help to solve the world’s problems. This wisdom does not belong to any one culture or religion, nor does it come only from the West or the East. Rather, it is a tradition of human warriorship that has existed in many cultures at many times throughout history.

I

N

T

IBET, AS WELL AS

many other Asian countries, there are stories about a legendary kingdom that was a source of learning and culture for present-day Asian societies. According to the legends, this was a place of peace and prosperity, governed by wise and compassionate rulers. The citizens were equally kind and learned, so that, in general, the kingdom was a model society. This place was called Shambhala.

It is said that Buddhism played an important role in the development of the Shambhala society. The legends tell us that Shakyamuni Buddha gave advanced tantric teachings to the first king of Shambhala, Dawa Sangpo. These teachings, which are preserved as the

Kalachakra Tantra,

are considered to be among the most profound wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism. After the king had received this instruction, the stories say that all of the people of Shambhala began to practice meditation and to follow the Buddhist path of loving-kindness and concern for all beings. In this way, not just the rulers but all of the subjects of the kingdom became highly developed people.

Among the Tibetan people, there is a popular belief that the kingdom of Shambhala can still be found, hidden in a remote valley somewhere in the Himalayas. There are, as well, a number of Buddhist texts that give detailed but obscure directions for reaching Shambhala, but there are mixed opinions as to whether these should be taken literally or metaphorically. There are also many texts that give us elaborate descriptions of the kingdom. For example, according to the

Great Commentary on the Kalachakra

by the renowned nineteenth-century Buddhist teacher Mipham, the land of Shambhala is north of the river Sita, and the country is divided by eight mountain ranges. The palace of the Rigdens, or the imperial rulers of Shambhala, is built on top of a circular mountain in the center of the country. This mountain, Mipham tells us, is named Kailasa. The palace, which is called the palace of Kalapa, comprises many square miles. In front of it to the south is a beautiful park known as Malaya, and in the middle of the park is a temple devoted to Kalachakra that was built by Dawa Sangpo.

Other legends say that the kingdom of Shambhala disappeared from the earth many centuries ago. At a certain point, the entire society had become enlightened, and the kingdom vanished into another more celestial realm. According to these stories, the Rigden kings of Shambhala continue to watch over human affairs, and will one day return to earth to save humanity from destruction. Many Tibetans believe that the great Tibetan warrior king Gesar of Ling was inspired and guided by the Rigdens and the Shambhala wisdom. This reflects the belief in the celestial existence of the kingdom. Gesar is thought not to have traveled to Shambhala, so his link to the kingdom was a spiritual one. He lived in approximately the eleventh century and ruled the provincial kingdom of Ling, which is located in the province of Kham, East Tibet. Following Gesar’s reign, stories about his accomplishments as a warrior and ruler sprang up throughout Tibet, eventually becoming the greatest epic of Tibetan literature. Some legends say that Gesar will reappear from Shambhala, leading an army to conquer the forces of darkness in the world.

In recent years, some Western scholars have suggested that the kingdom of Shambhala may actually have been one of the historically documented kingdoms of early times, such as the Zhang Zhung kingdom of Central Asia. Many scholars, however, believe that the stories of Shambhala are completely mythical. While it is easy enough to dismiss the kingdom of Shambhala as pure fiction, it is also possible to see in this legend the expression of a deeply rooted and very real human desire for a good and fulfilling life. In fact, among many Tibetan Buddhist teachers, there has long been a tradition that regards the kingdom of Shambhala, not as an external place, but as the ground or root of wakefulness and sanity that exists as a potential within every human being. From that point of view, it is not important to determine whether the kingdom of Shambhala is fact or fiction. Instead, we should appreciate and emulate the ideal of an enlightened society that it represents.

Over the past seven years, I have been presenting a series of “Shambhala teachings” that use the image of the Shambhala kingdom to represent the ideal of secular enlightenment, that is, the possibility of uplifting our personal existence and that of others without the help of any religious outlook. For although the Shambhala tradition is founded on the sanity and gentleness of the Buddhist tradition, at the same time, it has its own independent basis, which is directly cultivating who and what we are as human beings. With the great problems now facing human society, it seems increasingly important to find simple and nonsectarian ways to work with ourselves and to share our understanding with others. The Shambhala teachings or “Shambhala vision,” as this approach is more broadly called, is one such attempt to encourage a wholesome existence for ourselves and others.

The current state of world affairs is a source of concern to all of us: the threat of nuclear war, widespread poverty and economic instability, social and political chaos, and psychological upheavals of many kinds. The world is in absolute turmoil. The Shambhala teachings are founded on the premise that there

is

basic human wisdom that can help to solve the world’s problems. This wisdom does not belong to any one culture or religion, nor does it come only from the West or the East. Rather, it is a tradition of human warriorship that has existed in many cultures at many times throughout history.