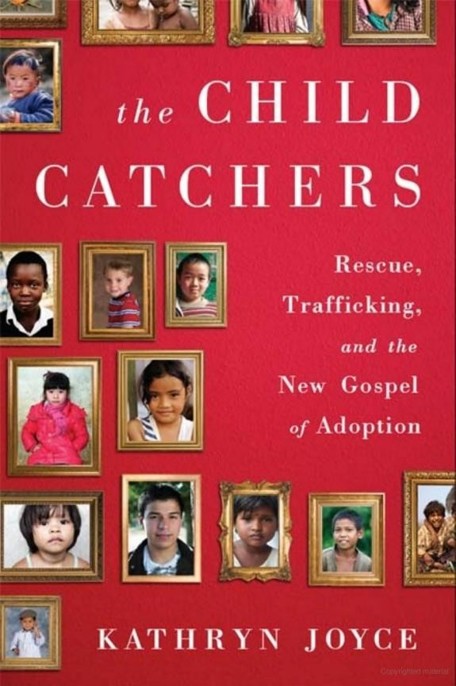

The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption

Read The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption Online

Authors: Kathryn Joyce

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Adoption & Fostering, #Political Science, #Political Ideologies, #Conservatism & Liberalism, #Religion, #Fundamentalism, #Social Science, #Sociology of Religion

the

CHILD

CATCHERS

the

CHILD

CATCHERS

Rescue,

Trafficking,

and the

New Gospel

of

Adoption

KATHRYN JOYCE

P

UBLIC

A

FFAIRS

New York

Copyright © 2013 by Kathryn Joyce.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs™,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Book Design by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Joyce, Kathryn, 1979–

The child catchers : rescue, trafficking, and the new gospel of adoption / Kathryn Joyce.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58648-943-4 (e-book)

1. Adoption—Religious aspects—Christianity. 2. Abortion—Religious aspects—Christianity. I. Title.

HV875.26.J6 2013

362.734—dc23

2012044316

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my family

“It is one hundred years since our children left.”

—attributed to town records of Hamelin, 1384

CONTENTS

Preface

1New Life

2The Touchable Gospel

3Suffering Is Part of the Plan

4Inside the Boom

5A Little War

6Pipeline Problems

7A Thousand Ways to Not Help Orphans

8Going Home

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Before I met Sharon I didn’t think about adoption as something that evangelical Christians particularly cared about, or at least not in families like Sharon’s—large, homeschooling families in which the parents already have lots of biological children. Sharon isn’t the sort of person you visualize when you think of an adoptive mother yearning for the child she’s adopting to “come home,” as they say in the adoption world. After all, Sharon wasn’t infertile. In keeping with her religious beliefs and as part of an evangelical movement that promotes prolific fertility, she had already had seven children biologically, and now in her mid-fifties, she was no longer particularly young.

I first got to know Sharon, who asked me not to use her real name, in the spring of 2007 when I was reporting on a group of evangelicals who didn’t believe in contraception but thought Christians should accept as many children as God gave them—hence Sharon’s seven. We met at a celebration hosted in Virginia by a fundamentalist homeschooling publisher, a sort of training ground for some of the people who would go on to become Tea Party activists several years down the line. (True to form, many of the men at the event walked the grounds in tricorner hats and kneesocks while the women donned colonial gowns.)

Sharon, a homemaking wife to a gentle and soft-spoken pest exterminator, was an eagerly outgoing woman with shoulder-length brown hair, a frank, makeup-free face, and a playful enthusiasm for culturewar sparring. We struck up a strange friendship, exchanging scores of e-mails, letters, and calls over several years, much of it concerning the difference in our world views: Sharon is an avid evangelizer and adheres

to the self-described “patriarchy movement,” while I am a secular, feminist journalist who covers religion and reproductive rights. We argued a lot about abortion.

In time Sharon, who struck me as a lifelong spiritual dabbler, trying on a dozen denominations and New Age paths before returning to the conservative Baptist beliefs of her childhood, developed a new calling. As 2007 rolled into 2008, Sharon became increasingly “convicted” that God was calling her to adopt more children into her family—possibly a brother and sister from an orphanage outside Monrovia, Liberia, or maybe a blind girl from Guatemala, or one of several infants recently born in the United States. She found these children by looking online at the websites of various Christian adoption agencies and ministries, which seemed to grow in number by the week.

The family created a blog that referenced a verse of scripture that was increasingly important in evangelical circles, James 1:27: “Pure religion is this, to help the widows and orphans in their need.” They began asking friends and family for donations to help defray the tens of thousands of dollars in adoption costs needed to “bring an orphan home.”

But Sharon was slightly behind the curve in the places from which she was seeking to adopt. When she began looking into Guatemala, the country was on the cusp of shutting down its huge adoption program, which had been sending adoptable children to the United States at a rate of one in every one hundred Guatemalan children born. That booming system, fueled by a seemingly insatiable demand from prospective US parents, had led to a number of abuses, including coercion of Guatemalan families, child buying, and even kidnapping. Things didn’t look much better in Liberia, which had become an adoption cause célèbre in the Christian anticontraception movement that Sharon followed and a particular trend in her own southern city. One of Sharon’s friends, she claimed, had adopted fourteen children from Liberia, and members of several churches in nearby suburbs adopted almost all the members of a Liberian orphanage group. In 2009, however, just as had happened in Guatemala, Liberia’s government suspended international adoption there as well. They were responding to numerous complaints about unethical adoption practices, including allegations of child trafficking after one unlicensed US Christian adoption ministry—the same ministry Sharon had hoped to use for her adoptions—was accused of trying to fly children out of the country without authorization.

Undaunted, Sharon began trying to adopt domestically, within the United States, spurred on by the experience of friends who had received a

newborn baby within three days of applying thanks to a new “Safe Haven” program that allowed mothers to abandon children to public authorities without penalty and without the formalities (or safeguards) of officially relinquishing for adoption. “I will make you the first to know that my husband agreed today to pursue a newborn domestic adoption in Florida,” she wrote me triumphantly one day. Not long after came another message, asking me whether I thought it would be wrong “to attempt to talk a woman out of an abortion and ask her to let me adopt the child instead?”

I hadn’t thought about it much before, but when Sharon asked the question, I realized I did think it was wrong. Sharon countered with an argument borrowed from one of her new “adoption friends,” someone she had met through an online community of women who had adopted or were seeking to. The friend assured her that “When you take one of these children, you are literally saving them from the ghetto life in America.” Sharon began to support programs that encouraged women with unplanned pregnancies to carry the pregnancy to term and relinquish the child for adoption.

She also compiled a “birthmother letter” and a packet of information about her family, including photos of their children and house as well as descriptions of the lifestyle they could offer. She sent it out to Christian adoption agencies and updated the fundraising widget on her website. She quarreled with friends and neighbors when they lagged in writing reference letters for her home study—part of the adoption agency approval process—and began writing me using the acronyms of the adoption world: AA for African American or SN for special needs.

She alerted me in excitement every time a new possibility for adoption emerged, each of which might send her off to Florida or Texas or Utah at a moment’s notice. She became invested in one potential child after another, leaping quickly from news that a child might be available to imagining the child in her family and then being crushed when the birthmother chose another couple, as often happens in domestic adoption.

Sharon’s “best adoption friend,” a woman who had adopted multiple times, wrote her in sympathy, telling her to hold out hope—more babies were being born every week—and if she wasn’t chosen, that meant that this was not meant to be her baby. “God knows when each child is conceived where they will grow up and once you have YOUR baby you will understand what I am saying,” she comforted.

When Sharon received another rejection, she cried and came down with headaches. She wrote me that she was exhausted with the entire

process and didn’t think she could continue. But she always came up looking for other options.

Part of me was baffled by Sharon’s fervor, and part of me recoiled, though at first I couldn’t understand why. I wondered why Sharon was throwing herself into such a punishing process when she had seven children at home. The tears she shed over kids who went to other adoptive parents would have seemed more understandable coming from an infertile couple who had been passed over and were mourning yet another lost possibility to parent. If her motivation was to save orphans in need, why did she seem more disappointed than relieved when children she had looked at were adopted elsewhere?

After my long discussions with Sharon I began to notice adoption more and more as I reported on conservative Christian social movements. As I looked more closely and spoke to more people involved in adoption—whether those seeking to adopt, like Sharon, or parents whose children were sent for adoption, or adoptees themselves—I came to realize that Sharon’s convictions were part of a larger picture in evangelical America. Across the United States a much wider spectrum of evangelical churches than just Sharon’s very conservative community had begun to view adoption as a perfect storm of a cause: a way for conservative churches to get involved in poverty and social justice issues that they had ceded years before to liberal denominations, an extension of pro-life politics and a decisive rebuttal to the taunt that Christians should adopt all those extra children they want women to have, and, more quietly, as a window for evangelizing, as Christians get to “bring the mission field home” and pass on the gospel to a new population of children, effectively saving them twice. What that meant on the ground was that churches were witnessing what they called a “viral” movement, with adoption becoming so popular in conservative, largely white, and often southern congregations that some churches saw their members collectively adopt upward of one hundred children in just a few years. This was matched by increasingly direct support from pastors and dozens of emerging Christian adoption ministries, conferences, and coalition groups.