The Cannabis Breeder's Bible (34 page)

Read The Cannabis Breeder's Bible Online

Authors: Greg Green

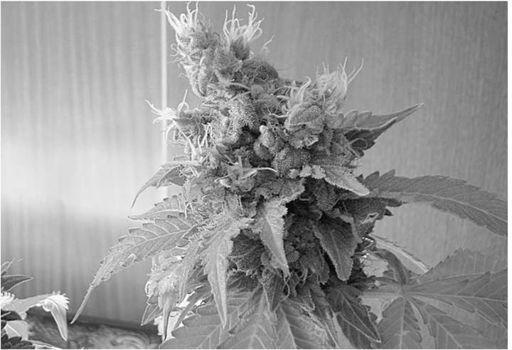

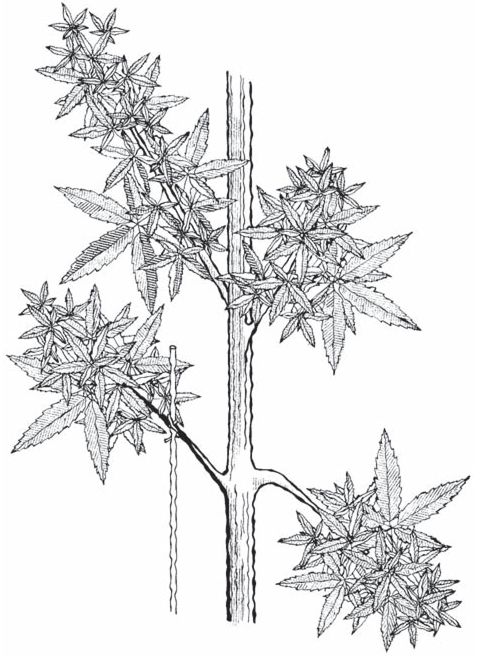

Note the breeding traits involved in various bud production areas of a branch. Notice how flowering distribution and branching support play major roles in how well the plant can handle the weight of each.

The way to counteract this problem is through breeding for shorter internodes. This has been done to some degree for Skunk#1 with variations like Super Skunk and Mazar. By breeding for shorter internode development the branches have fewer gaps. Also the breeder will try to produce bud at most of the node regions, through breeding, to cover these gaps with flowers. That way the bud amounts are more evenly distributed across the entire branch instead of ending up as one whole flowering mass at the growing tip.

11

This prevents the branch from bending too much, however some indoor strains are designed to have high cola bud concentration amounts with the anticipation that the grower will tie the branches up. For this reason breeders must also take into account that some growers like to prune, top and train their plants. This has an impact on branching numbers and final yields. You should experiment with your strain to see how well it responds to these plant care techniques. Sometimes a pruned, topped or trained plant can produce much lower yields, sometimes much greater. The only way you can know how well your strain reacts to these branching control techniques is to prune, top and train your strains. Sometimes breeders recommend pruning with their strains because it can increase yields, however some growers make the mistake of thinking that this applies across the board to all cannabis strains.Your 2-pound-producing monster plant can quickly become a 1-ounce-producing average cannabis strain because of pruning.

Compact buds are nice and dense, but also top heavy. This Bogbubble plant from breeder BOG sure can bend.

Plants have a genetic threshold for bud production and the distribution of these bud amounts across the plant also depends on branch production. To be more accurate, we are talking about node development here. New branch formations create new node regions. All node regions are potential bud areas. We will look more closely at the relationship between branch numbers, node regions and yields in a moment.

Calyx/Leaf Ratio

This is something that breeders have noticed over the years. If you look at a flowering cannabis plant you will see that each node should be developing bud. A node occurs at a junction point where a new branch or new stem is produced. Calyxes mainly develop at the node regions. This is especially true during the early days of calyx development. For every node region there is at least one branch developing above or beyond it with at least one leaf at the tip of the branch that the node is located on. Thus if you count the leaves on your plant, you should have a minimum node/leaf ratio of roughly 1:1. Since a calyx will develop at the node region there should also be a calyx/leaf ratio of 1:1 during the early stages of calyx development. As the plant increases calyx development the ratio should rise to 2:1 and beyond.

This Ladybird beetle is hunting Aphids on the top cola. Note that this strain has a very low calyx/leaf ratio. Photograph by Kissie.

This cannot be said for all plants. Some nodes do not develop a calyx and thus do not flower. In cases like this the 1:1 ratio can drop down to 1:2 or even as low as 1:6 or 1:10. Plants that have a low calyx/leaf ratio such as 1:3 or 1:4 are inefficient for a grower’s purposes unless the quantity of bud created at the other calyx sites compensates for these invalid node regions. This is the first thing we need to know with regard to the calyx/leaf ratios.

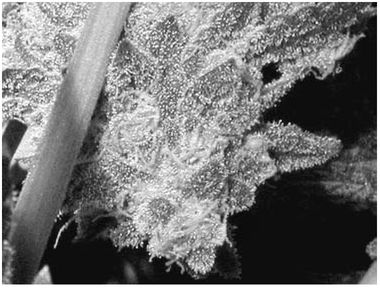

The main focus of our calyx/leaf ratio scrutiny are the colas, which in most cases is just a single top cola. (You may have pruned your plant, though, and this would lead to multiple cola heads, or possibly your plant has naturally produced more than one top cola). If you look at any top cola you will see that tiny branches are created to support node development, calyx and flowers. This is especially observable during and after manicuring or after breaking up your bud from the branch after curing. These branches are usually tightly packed together, giving the top cola its density. If you look closely at a plant that has been bred well for a good calyx/leaf ratio, you may find 20 or more calyx areas with only one leaf supporting the branch but several calyx organs developing at these nodes. In general when a breeder refers to calyx/leaf ratio, he is talking about the top cola’s calyx/leaf ratio. A poor top cola calyx/leaf ratio is 1:1, while the normal will be around 2:1. A good calyx ratio is around 4:1 or 5:1. An excellent calyx/leaf ratio would be 7:1 or even 10:1 and beyond.

Low calyx to leaf ratio, medium calyx to leaf ratio and high calyx to leaf ratio.

Calyx development means more bud sites, but may not mean higher yields. Even a calyx/leaf ratio of 20:1 may produce low yields (a good example is the strain ‘Flo’). If you are not going to be putting on the bud weight then what is the point to having a high calyx/leaf ratio? Again, breeding is interlinked in so many ways. Most breeders trying to develop high calyx/leaf ratios will also try to develop high bud quantities. Generally in growing terminology a high calyx/leaf ratio is expected to mean that the strain is capable of high yields. High calyx/leaf ratios are also easier to manicure. Plants with high yields but low calyx/leaf ratios are harder to manicure because more leaves must be trimmed. Calyx/leaf ratios are not related to potency.

Color

In general cannabis is a green plant. Sometimes hues of purple or red may crop up in a healthy individual but overall the plants should still display a lot of green. It is not recommended that you try and change the green color and it is also highly unlikely that you will succeed without using chemicals. Cannabis plants are green because they reflect green light that they do not need for photosynthesis. If they are any other color then they will absorb green light, which will not be beneficial or used in photosynthesis and they may reflect a color that they need. Sick plants can change all sorts of different colors from black to blue to yellow to red, but we are not interested in breeding sick plants; we are interested in working with healthy ones. Cannabis flowers can vary in color but are mostly green too.

Chlorophyll is the compound in cannabis plants that gives it the green look because chlorophyll in the leaves reflects the green light, but during the flowering period, especially toward the end of flowering, chlorophyll may break down and reveal other pigments that it is hiding. This can produce all sorts of different-colored buds. Purple bud color is due to the anthocyanin pigments in the plant that are allowed to express through the degraded chlorophyll. But this has to be a trait in the plant in order for it to occur. If the plant does not have a colorful trait for anthocyanin pigment to come through after chlorophyll degradation then it will not be observed. It is a genetic trait. There are various parts of the plant’s physiology that contribute to color.

It’s incorrect to see color as something like a varnish on the plant. Color has a lot to do with the actual chemical makeup of the plant and the various parts they inhabit or move through. Pigments are the natural coloring matter in plant tissue, chlorophyll being the most predominant.

Carotenoids are a class of mainly yellow or red pigments of wide natural occurrence having the conjugated molecular structure typified by carotene. Carotene is an orange or red hydrocarbon (C4

0

H56) of which there are several isomers (common in carrots and many other plants and a precursor of vitamin A). Isomers consist of two or more compounds, or of one compound in relation to another, composed of the same elements in the same proportions, and having the same molecular weight, but forming substances with different properties owing to the different grouping or arrangement of the constituent atoms. In the actual formation of the substances a color is allocated to it. If you look at carotenoids that are red and yellow you’d see that red and yellow combine to create other colors and these give off different hues associated with carotenoids, such as brown and orange, which are very common on floral parts of the cannabis plant.

There are many ways to breed a plant so that when chlorophyll degrades the green is either totally transparent, revealing the color below, or it only loses a percentage of its color or tone which mixes with the color underneath. Chlorophyll amounts can be controlled in harvest by removing as much N as possible at the end of flowering. Also removing K will help reveal the underlying color. Remember though that nutrient removal will also affect plant health and yields.

The way you grow your plant and what lights you use are just as important in revealing your breeding colors as breeding itself. Generally a flowering plant that has high levels of N in the medium during flowering time will not reveal much of your color work. In most cases flower color will develop from one shade to another so the breeder should take those variations into account. A black budded plant may start off with red or orange or even white

When breeding for color try to work with strains that have a propensity to display lots of various colors so that you have a large selection of hues and their respective combinations to choose from. By creating hybrids and then true breeding specific color traits you will be able to locate, mix and lock down traits for color expression. It is great to see some breeders produce plants with dark green/purple leaves and great big black buds. There are so many different color types out there; experiment a bit with different strains before you find a beauty you can work with.

A resin thick, high calyx to leaf ratio, Black Domina strain from Sensi Seeds. Photograph by Mikal.