The Cannabis Breeder's Bible (33 page)

Read The Cannabis Breeder's Bible Online

Authors: Greg Green

Buds (of the node type) are compressed undeveloped shoots and are either stalked/lateral or terminal. They are found at the nodes, which are points on the stem where leaf, branch, stem, calyx and flowers are created. The space between two nodes is called the “internode.” The internode mostly refers to the space between stems on the main stem, but it can also describe the space between node regions on a branch. “Leaf scar” is a place on the stalk left where a leaf was previously attached. “Bud scale scar” is a mark on the stem where a bud was previously attached.

When the terminal bud grows small growth rings are formed on the stem. Sometimes these scar marks can be clearly seen.

Cannabis is treated as an Herb because it does not appear to have too much woody tissue on the stem. Woody tissue plants are normally referred to as shrubs, trees and vines. The cannabis plant is an annual plant that lives for one year or season, reproduces, and then dies—however if there is not a harsh winter or the plants are looked after with care, they can continue growing for a number of years, especially if the grower chooses rejuvenation (

CGB,

p. 172). Biennial plants live for two years or seasons, reproduce and then die. Perennial plants live for several to many years or seasons. The important thing to note is that cannabis can also be perennial if the given environmental conditions allow it to survive.

The “petiole” is the stalk of a leaf that connects to the branch or stem. The “blade” is the term used to describe the flat, wide portion of the leaf. Cannabis plants have several blades on each leaf and these can range in length, width and thickness between species and strains.

The leaf is not a simple one, so it falls into the “compound” leaf category. It is neither “once pinnately compound” or “twice pinnately compound”, but “palmately compound,” the difference being that palmately compound leaflets arise from one point at the base of the leaf. What we are looking at is the projection and division of a cannabis leaf.This area is correctly called the “lobe”.There are only two basic categories of lobes and these are “pinnate lobes,” which have a main mid-vein along with secondary veins arising from it at intervals, and “palmate lobes,” where the main veins all arise from one point at the base of the leaf.

The structures we have looked at here can be changed on a very wide level as long as cannabis continues to breed with cannabis. You will also find some discrepancies between biologists noting the different types of morphology that the cannabis plant expresses, however this is not uncommon for a plant family so diverse in variations as cannabis is.

Breeding the Morphology

Cannabis is cannabis, whatever way you look at it. If you stand back and look at several different strains for different cannabis species types you will see variations and similarities. You can spot a cannabis species and strain type a mile away if you know what to look for. Many experienced growers can separate species into strain classifications like Kush, Skunk and Berry by looking at (or trying) the expressed phenotypes of each plant. We may find a group of strains from a species such as Kush strains, Haze strains, Skunk strains and Jack Herer strains. Through experience we can group strains like this together by their appearance. They all share common traits that make up the overall shape but those traits may contain variations. A good breeder knows and understands different strains. When breeders work on cannabis strains they do not need to change the way they think about the different cannabis species as whole. They might have to take certain factors into consideration but they are working with the same template each time. That template is Cannabis.

Here is a list of traits that we need to take into account when working on a strain. Floral traits, which will be covered further on, take other elements into consideration, like taste and smell.

• adaptableness/adaptability

• calyx/leaf ratio

• curing and manicuring

• floral traits

• maturity (including flowering times)

• size

• yield

• branching

• color

• disease resistance (including pests)

• leaf traits

• seed characteristics

• vigor

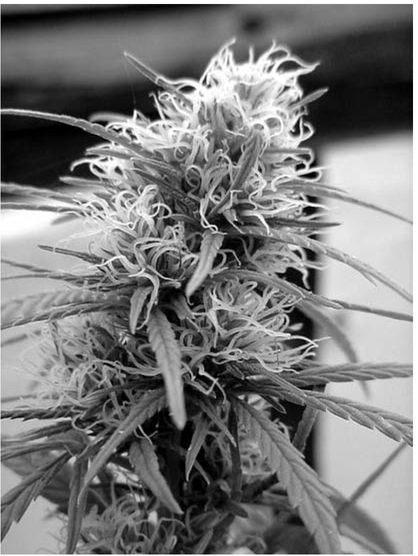

Vigorous pistil production is a good sign that an outdoor plant is adapting well to the environment. Photograph by Anton

Adaptableness/Adaptability

Some strains are not very adaptable. For instance, Sativa strains are not very adaptable to indoor growing environments without vigorous pruning or breeding. Sometimes the genetic minimum internode lengths are so long that even 6-nodelevel-tall plants are over six feet high, pushing the limits of what the grow room is designed for. At the same time a breeder who creates the perfect ScrOG strain is not going to be making an adaptable plant to suit other growing conditions, like outdoor growing.

If you want to create an all-round adaptable plant then you need to work on a strain that is easy to grow in warm/cool conditions, indoor/outdoor/greenhouse and can be controlled by the grower via pruning. The only way you can do this is to test the strain out yourself under these different conditions to see if you make the strain more adaptable.

Generally, the less variations strains have the less adaptable they will be. Unstable hybrid strains tend to be more adaptable than true-breeding stable strains, depending on the environment. Remember hybrid vigor? Adaptable plants grow to suit the environment. Inflexible plants grow better in an environment that suits them.

Since the market is changing and breeders are creating more and more specialized strains, you can expect to find less adaptable plants on the market. Is there a niche in the market for adaptable plants? Well, most Sativa strains and pure Haze strains carry a lot of variations and these are expressed in the phenotypes. Unstable Sativa strains can produce fine mother plants during the selection process. The best way to create adaptable plants is by creating new hybrids with lots of variations.

Most grow books have erroneously suggested that varieties that perform well under artificial lights will also perform well outside or in a glass house under natural sunlight and that outdoor plants do not do well indoors. Although the later part of this statement is true, certainly the first part is not correct.

Yes, it is true that all cannabis strains can be grown indoors, outdoors or in greenhouses. It is also true that if we are looking for the best results we should stick to what the breeder recommended. It is a mistake to assume that indoor breeding projects can produce good outdoor plants. Outdoor maturity dates and outdoor flowering times are not selected for when breeding for an indoor environment. Indoor breeding programs also do not select for outdoor sexual maturation or the plant’s response to the outdoor photoperiod. The outdoor environment also has a very different impact on the plant’s final expressed phenotype when compared to plants grown under artificial lights indoors. The outdoor environment, and sunlight, will cause variations in the expressed phenotype of the plant. This can be identified in traits like smell and taste. Pests should not be found indoors in a sterile breeding room. Outdoors, pests can be everywhere and of multiple types. Sterile breeding rooms may leave a breeding project open later to problems like mold, fungi and pest attack. We will look at how to solve this later on.

The bottom line here is that stable lines are not very adaptable and growers want stable lines. In short, most breeders do not breed for adaptability. If you want to breed for adaptability then simply keep producing F1 hybrids using nonrandom mating programs in various different environments. The more variations a plant has the more adaptable it can be.

Branching

Branching is first determined by node levels and then sub-branching. Branches add weight to the plant and can also stress the stem. Branching can be controlled by pruning, but every strain has:

• a genetically set branching limit during vegetative growth,

• a genetically set branching limit after vegetative growth.

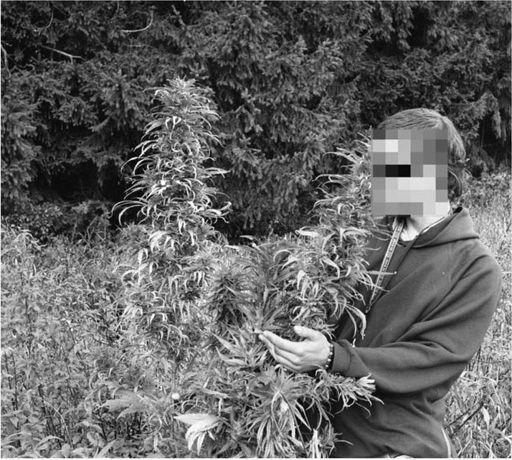

Sometimes branches get so top cola heavy that they need to be tied together. Photograph by Kissie.

Sativa strains tend to have lots of branches that are spaced out between long internodes and node regions. This makes Sativa strains more loose than Indica plants. Indica plants have shorter internodes and that makes the species more compact than Sativa plants. Through breeding we have been able to totally control this and swap the traits around.

When working on branching traits we must also consider how productive the branches will be and how they will help boost yields. Each node is a potential bud site and each branch will take up some amount of space. We must also consider the fact that if we grow outdoors and it rains then each branch and leaf will be covered in some rain drops. Rain drops do add weight to the plant and I have seen some strains bend completely over during vegetative growth and snap at the stem because of heavy rainfall. (It is not uncommon to find outdoor plants with colas lying in dirt contracting mold and other plant diseases because of the added weight of a recent rainfall and the fact that the bud mass could not be supported by the branch. This condition is solved by tying up the branches or breeding stronger branches into the strain.)

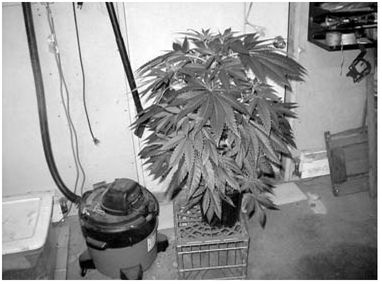

A nice squat and compact Indica/Sativa plant. Breeder BOG has kept the internodes short on this one.

During flowering the branches are a bit stronger and the stem is thicker to support bud growth, but it can still snap or bend severely during rain if the branch is not strong enough. Many indoor strains are not bred for outdoor use and many of these strains can collapse under rainy conditions. Wind is important to consider as well. Some strains are better suited for the wind than others. A strong gust can topple strains that were devised for indoor use.

When breeding an outdoor strain make sure that you create a sturdy plant that can cope with all weather conditions. You must test your strains and breeding projects in these conditions.

Skunk#1 is a very interesting plant to look at. Low down, the bottom branches tend to curve upward with long internode gaps that do not produce much bud at the internodes except for the tips, which produce above-average size colas. These branches tend to bend over with the weight of the buds (a trait that is common with many other strains of cannabis). As the branch bends the light-to-bud distance increases and this is the plant’s own natural way of preventing itself from being overburdened with bud weight that can effectively snap the branch or stem. The less light these branches receive, the less the rate of photosynthesis will be and the result will be less bud production. All strains tend to do this to some degree when the flowers are getting too heavy for the plant to manage. This gravitational response to unmanageable yields is usually countered by the grower, who ties up the branches to keep the plant producing high yields. With some strains, during harvest when the branches are untied, the colas will flop down to the sides, almost hitting the floor.