The Bolter (25 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

A Happy Valley picnic

The weekend—or Saturday-to-Monday—house parties varied. There were the staid ones, when Idina and Joss invited people they knew less well, or those who were well behaved. These included European grandees in more conventional marriages, such as the writer Elspeth Huxley’s parents, Jos and Nellie Grant; Lord and Lady Delamere; unattached men such as Gilbert Colvile and Berkeley Cole, and the odd colonial official or district commissioner.

The evenings began with cocktails: White Ladies, Whisky Sours, Bronxes, and gins in varying colors and effervescences. Eight thousand feet up, in that thin air, the alcohol hit hard and fast and the conversation quickened.

30

Dinner was at a long, polished table laid with a platoon of silver knives and forks and crystal glasses, linen napkins folded around each. Back in England few of even the grandest houses raised their culinary threshold above English suet. Here, halfway across the world, up in the skies, Idina and Marie coaxed four-course French meals

out of a shack of an outdoor kitchen. All that was missing were copious clarets and Burgundies. Wine was harder to come by than in Europe. It was there, somewhere. But even if brought out it didn’t mix well with the spirits before and after. Instead they drank more whisky—and ice cold beer.

Conversation, just as on landed estates back in England, centered on farming methods: the latest ones attempted; the old ones discarded. They talked of gardens, what would and wouldn’t grow, how to manage their lawns, irrigate ponds. And they talked about books. With no cinema around the corner and the only theater a day’s journey away in Nairobi, books, which could be posted, carried, lent, and exchanged, formed the cultural currency. Like one vast, loosely arranged reading group, the Kenyans strove to read what everyone else was reading—and talking about. In their half-pioneer, half-prisoner lives, the latest published theories and stories were their peephole to the rest of the world. And Idina, her shelves overflowing, with a view on each one and compulsively recommending and lending the latest she had enjoyed, was the Kenyan queen of books: “No-one knew more about contemporary literature than Idina.”

31

She could devour a novel a day, falling into the characters’ emotions, living their adventures vicariously from her deep sofa halfway up an African mountain.

And, halfway up that mountain, Idina threw different sorts of parties too. To these, she and Joss invited more carefully chosen friends and acquaintances. These had usually spent some time in London and Paris since the war. They had been to parties where the hostess turned up naked, they had joined in the after-dinner stunts designed to shock, they had drunk too much, ended up group-skinny-dipping at midnight (years of boarding-school dormitories had whittled away any sense of body-shyness), and, just as many of their parents had done, they had fallen in and out of bed with their friends. Having a good time meant going as far as they dared. And then a little beyond that.

Idina and Joss’s friends arrived, bathed, slipped into their pajamas, were handed a cocktail, and were ushered through into the memsahib’s bathroom. There Idina lay simmering in green onyx, ever-present cigarette holder and crystal tumbler on standby, welcoming them in. She chattered as she washed, climbed out, dried herself, and dressed. They drank and talked some more and the pace quickened as the alcohol flowed through their veins. A gramophone would be brought in, its handle wound, a record put on—the latest jazz arrived from England with Idina’s pile of books—and off they went, dancing in pajamas

almost as soon as the sun had set. Formality broke into the evening with dinner. The same four-course French feast, washed down by whisky. Cocktails again. The alcohol and altitude together sent them as high as kites, with almost no need for the odd line of cocaine.

Frédéric de Janzé, who was a frequent guest of Idina’s, describes the after-dinner scene at Slains in

Vertical Land

, named after the hillside rising sharply up behind the house. “The dark all around”

32

—only the firelight would be flickering. Idina would stand “with her back to the fire, gold hair aflame,” wearing not pajamas but Kenyan tribal dress—a “red and gold kekoi” that matched both the flames and the color of her hair. Naked underneath, she had tied the long cloth around her and over her breasts. Her face was “framed by the dull beam, topped by buffalo horns. Like a weird lily swaying on a Japanese screen, she alone is living in that room.” Her guests, burning with alcohol and physical frustration, sprawl around her—“sunk in chairs, legs crossed on the floor, propped up against the wall, our eyes hang fascinated on that

slight figure… always the same power. Men leave their ploughs, their horses are laid to rest, and, wonderingly, they follow her never to forget.… The flames flicker; her half-closed eyes awaken to our mute appeal. As ever, desire and long drawn tobacco smoke weave around her ankles, slowly entwining that slight frame; around her neck it curls; a shudder, eyes close.” And then she started the games.

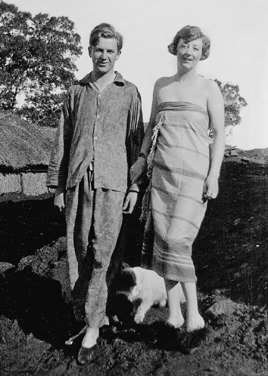

Idina and Joss, in red and gold kekoi and pajamas, on their Kenyan farm, Slains, 1924

One short Saturday-to-Monday with no chance of surreptitious lunches and teas in between compressed the time available to select a new bed companion. Games—British after-dinner games with a twist—were a way to move matters on. Back in London, at Oggie’s, at everywhere broad-minded enough to invite Idina, they had “stunted” after dinner. Here these games were Idina’s stunts. They had another purpose too. Games with Idina as master of ceremonies were a way for her to exercise some control over who Joss would sleep with—or to appear to do so.

Joss did not drink alcohol. He said, quite openly, that he did not want “to impair my performance.”

33

Instead he circled the room filling the glasses, while Idina decided upon the game for that evening. They started with word games, such as which was the real first line to which book, then charades, a bit of acting, singing, dancing, then more dancing to the gramophone. Happy swing, soulful jazz, blues that hollowed out a listener’s insides. More alcohol. Then back to Idina, standing in front of the fire, long, black cigarette holder at her lips. The tension around her mounted.

The bedrooms were locked, and Idina held the keys. She spread these out on a table and with a roll of dice, the turn of a card, the blow of a feather across a sheet stretched between trembling hands, the keys were allocated and each guest would win a partner for the night.

AND THEN, EXACTLY ONE YEAR

after Idina had brought Joss to Kenya, after just about the length of time her marriage to Charles Gordon had lasted there, Idina discovered she was pregnant.

Chapter 16

R

umors were rife that Idina’s baby was not her husband’s. She had made as many enemies as friends in Kenya. Stories of the wild parties at Slains were hotly debated—though the debates often genteelly avoided the racier details. Those outside Idina and Joss’s charmed circle of invitees were split. Some, especially those who had been received more conventionally by Idina, refused to believe that such an elegant and intelligent woman might behave in this way—or that they could have failed to spot the signs of such salacious activity. Others nursed grudges over being left off the invitation list—even if events were a little too fast for their taste.

Idina’s neighbors, whom she barely knew, found themselves being quizzed as to the goings-on up at the Hays’. One, Mrs. Case, was so embarrassed at her ignorance that she sent her

watu

up to Slains to talk to the servants. Tales of confusion over whom the laundry collected from each bedroom should be returned to raced back down the hill and were widely disseminated. These were fueled by Joss’s bragging about his conquests at Muthaiga, dividing the women he had slept with into “droopers, boopers and superboopers.”

1

And Kenya’s chattering classes began to worry.

Just as the upper classes back in Britain feared the publicity of divorces among their ranks, so the middle-class settler farmers and the more prudish émigré aristocrats feared that the Hays’ misdemeanors undermined the settlers’ cause. The farmers were ceaselessly at loggerheads

with the colonial government over how much control they themselves could have over the colony and the extent to which their interests should be balanced against those of the native Kenyans and the other immigrant population, flooding in from India. The settler farmers’ argument was that they had worked extremely hard to turn virgin land into good farming soil and that they had therefore earned some legal and physical protection for their interests. If the settlers were seen to be a bunch of wife-swapping sybarites and in any sense “going native,” they would lose their moral authority and appear less safe as leaders of the British colony.

British colonial authority, like class divisions back Home, had long been based upon notional differences between groups. And these differences must, the colonial ethos went, be adhered to. Whatever the greater comfort of the native way of life, the Englishman abroad must not succumb. British hours must be kept—no siesta—British food must be served, and British standards of dress must be adhered to, however burning the sun. For men this was either suits or colonial white shirts, shorts, and stockings. For women, skirts or dresses. These must suggest a life of propriety and hard work. It was also vital that sun hats be worn at every opportunity to emphasize the superior fragility of white skin. These were the rules. And, in addition to the persistent stories that Idina was “going native” sexually (many of the native Kenyan men had several wives, and her rumored bed-hopping was seen to mirror this), she flaunted the sartorial norms: she wore trousers every day, just like a man. When she started to wear shorts it was, however, too much for one settler’s wife.

Lady Eileen Scott was the wife of Lord Francis Scott, the younger son of the Duke of Buccleuch. Francis had come out in 1919 on the same soldier-settler scheme as Charles Gordon, but Eileen and Idina could hardly have been more different. In the words of the Kenyan writer Elspeth Huxley: “Eileen Scott lingers in my memory draped in chiffon scarves, clasping a French novel and possibly a small yappy dog, and uttering at intervals bird-like cries of ‘Oh François! François!’ ”

2

Eileen was a daughter of the Earl of Minto, former Viceroy of India, and had been brought up to believe in the Englishman’s divine right and duty to rule. Eileen could not stand Idina, whom she regarded as undermining this principle at every turn: “Most of the women,” she wrote in her diary in despair, “wear shorts, a fashion inaugurated by Lady Idina who has done a lot of harm in this country. It is very ugly and unnecessary.”

3

Yet, whatever Idina wore, she could please neither Eileen Scott nor her like-minded white Kenyan farmers. Dressing to the nines met with as little approbation as wearing shorts. For glad rags gave the equally damaging impression that Kenyan life was frivolous. After a day’s racing at Nakuru, Eileen wrote: “Lady Idina was there in an Ascot gown with a lovely brown ostrich feather hat. Why she didn’t die of sunstroke I can’t conceive.”

Idina’s nonchalance in the heat and dust appeared worryingly un-British. The settlers were besieged by sun, dust, and insects and were offered little in the way of physical comfort as relief. While many women struggled to make themselves presentable, Idina appeared unperturbed. This drove Eileen to a fury: “Most of the women in this country, except Lady Idina, are burnt brick-red.… I wonder how Idina will enjoy trying to eat this type of food and washing out of a cracked old tin basin.… Everything is so intensely dry, it splits the face and hair.”

But Idina cared as little about these things as she did about whether other people knew whom she had slept with the night before. She simply lived by an entirely different set of rules: “she was somehow outside the comic, squalid, sometimes almost fine laws by which we judge as to what is and what is not conventional.”

4

Most settlers regarded sitting down to dinner late (thus failing to keep British hours) and keeping their servants up as flagrant mistreatment—whereas flogging for cleaning the family silver with scouring powder was par for the course. Idina did the opposite. Her predinner drinks occasionally dragged on, but she didn’t flog her

watu

. Instead, they regarded her with awe as she walked barefoot around the farm with them. Her excess of unworn shoes hardly endeared Idina to the Lady Eileens of Kenya, who couldn’t bring themselves to recount the rumors that Somali drivers had left Idina’s employ out of fear of being asked to sleep with her. But when the long-dreaded native Kenyan uprising did come and these other settlers found their houses being razed to the ground, Idina’s was left standing.