The Bolter (22 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

That ring plays a part of its own in

The Green Hat

. Arlen disguised it as an emerald. It was not the only part of Idina’s story he had to change a degree or two: much of the truth was too shocking to write literally, even when Arlen put pen to paper at the end of 1923. The divorce law had just changed, at long last allowing a wife to divorce her husband for infidelity, but public morality had not yet caught up. Instead of being twice divorced, Iris Storm is twice widowed.

Iris’s ring was given to her by her second husband because it was,

like her, “beautiful but loose.”

20

The ring will stay upon her finger only so long as she remembers to curl it. If she becomes distracted and forgets the ring, and her husband, it will fall to the floor as she herself will be falling from grace. For, as her husband tells her: “that is the sort of woman you are.”

21

Shortly after Iris loses the ring, she dies.

Idina wore the pearl Euan had given her until, long after Arlen had written, she, too, died.

AT THE BEGINNING OF 1923

a new twenty-year-old American actress moved into Oggie’s house. She had arrived in London to star in a show called

The Dancers

. One evening she appeared on the stage at the beginning of the play with long hair but by the final act had bobbed it to the microlength of the day. Within weeks she had gained herself a large following of female cockney fans, many of whom sheared their own hair during the performance, throwing locks onto the stage. Her name was Tallulah Bankhead.

Tallulah was one of Oggie’s new finds. She was exuberant and wild, inclined to shock given half a chance and certainly not dull but, compared with the practiced sophistication of the European women by

whom she was now surrounded, an ingénue. Oggie and Idina took her under their wing. They taught her about food and wine, showed her how to diet off her puppy fat, took her to Molyneux for her clothes and taught her how to be decadent with style. And then either Idina or Tallulah taught the other (for they both became known for doing this) how to empty several crates of champagne into a bath and climb in—with somebody else to keep them company.

Tallulah Bankhead

Bathing in champagne was not the only way in which Idina’s and Tallulah’s lives became entwined. In

The Green Hat

Arlen borrows the name of a boyfriend of Tallulah’s for the subject of the thirty-year-old Iris’s fatal romance with a younger man. The man in question, Napier, is starting his career in the Foreign Office and is being lined up to marry a debutante. Napier was the name of the 3rd Baron Alington and the owner of eighteen thousand acres of Dorset, with whom Tallulah had an on-off affair. Tallulah loved the story and played the part of Iris on the London stage (Garbo took the role in the movie

22

). Indeed, as Tallulah’s Napier did, Arlen’s Napier ends up marrying the suitable young debutante who had been lined up for him. For, in order to keep his heroine within the bounds of acceptability, Arlen has Iris demonstrate her overwhelming love—“if people died of love I must be risen from the dead to be driving this car now”

23

—by taking her own life, freeing her lover to marry his debutante, instead of ruining him by taking him herself.

But just before Arlen wrote, the now thirty-year-old Idina had done quite the opposite. She had at last found that “better life” in the form of one of Britain’s most eligible, albeit penniless, bachelors. He was a tall, blond twenty-two-year-old just starting on his career in the Foreign Office. His name was Josslyn Hay and he would one day inherit Scotland’s leading earldom. Idina amicably divorced Charles Gordon, who wished to marry a friend of hers, and married the young Josslyn. She then took him away from the debutantes, away from the Foreign Office, and back to Kenya. “I have done with England,” says Iris Storm, “and England has done with me.”

24

Chapter 15

I

dina didn’t have to marry Joss. She could simply have continued as his lover. Doing so would have been less shocking than taking a third husband. Idina’s greatest sin was not her need for new sexual excitement but that “she insisted upon marrying her boyfriends,” as her brother and others said,

1

thus shaking the traditional social structure grounded on lifelong marriages.

There were, however, several reasons to make Idina want to marry again. In part, she may have wished to play up her role as a socially outlawed femme fatale. For, to the outside world, her third marriage, to a man eight years younger than herself, was truly shocking. And the carousel of life at Oggie’s was no replacement for the security of marriage, a security which Idina, needing ever more strongly to be loved, yearned for.

More important, Idina was clearly smitten with Joss. Her infatuation smothered any hesitation she might have had about embarking on a third marriage. In any case, as Idina neither expected nor hoped for fidelity from Joss,

2

being married was a way to hold on to him. For “Idina, fragile and frail,”

3

the obvious solution was to marry Joss, but to have an open marriage.

4

Each of them could then have sex with whoever they felt like without their marriage being destroyed. And, after two years of living at Oggie’s, Idina had become used to having a variety of sexual partners. For this to work, nothing could be allowed to

become too serious. It was the well-tried and tested formula for upper-class marriage that they had grown up with.

Having, for over two years, lived from party to party, looking no further than the next pair of arms, Idina now started to plan her life. She would return to Kenya with Joss. They would buy a farm, raise a house, and build themselves a life out there and, this time, she would make it work.

The odds on this marriage being a success were, however, not in Idina’s favor. As well as her own less-than-encouraging track record there was the large age gap between her and Joss to contend with. Idina chose not to ignore this. Strangely, she appears to have mothered Joss at the same time as being his lover: “the child,” she calls him throughout her only surviving letter to his parents.

5

At two-thirds Idina’s age, Joss appears to have been filling not just the gap left by Euan but also the one left by her children.

Joss was serially unfaithful from the start. Idina professed not to mind.

6

She had, in any case, started off by sharing him. She had met him at the same time as another woman, an American named Alice Silverthorne, who was married to the young French Count Frédéric de Janzé, a sometime racing driver, sometime politician, poet, and member of Paris’s literati crowd of Marcel Proust, Maurice Barrès, Gertrude Stein, and James Joyce as well, of course, as being a friend of Oggie’s.

Alice was a beauty. She was raven-haired and porcelain-skinned, with violet eyes in a wide face. An orphan, she had inherited more money from an American meatpacking fortune than she knew what to do with and, as if bending under the weight of her riches, she appeared both fragile and almost frighteningly unpredictable. Joss and Alice yo-yoed in and out of bed with each other. Sometimes he went off with her for a few hours, sometimes a few days. But he always came back to Idina. Idina began to rely on Alice to return Joss to her, and Alice relied on Idina’s acquiescence whenever she and Joss had a fling. Gradually the two women became friends, waiting together for him to return from whichever third bed he had slipped off to.

Golden-maned, with strong, aquiline features carved on a languid and slightly weak-chinned face, Joss had a direct gaze and thick, wide lips that he curled up and down into grins and sneers—whichever, for that woman, would do the trick. At twenty-one he had the confidence of the women twice his age with whom he had been sleeping since he was a teenager. His grandfather was the Earl of Erroll, the hereditary

Lord High Constable of Scotland; his father was Lord Kilmarnock; as they died, Joss would climb the aristocratic tree. The only hitch was that there would not be a penny for him to inherit. The family had lost all its money, his father worked in the Foreign Office, and, shortly before Joss married Idina, even the ancestral Erroll home, Slains Castle, was more or less taken apart and sold for scrap. Although his parents could still afford to give him an allowance, it was not enough to live on. Joss would either have to work for a living or marry a woman who would support him. Idina could.

Although not as rich as Alice, Idina still had some of her ten thousand pounds, a generous mother, and an allowance from her brother, who had inherited a large amount of money in 1919 when their uncle, Tom Brassey, had been knocked down by a London taxi. And eventually Idina should receive a share of the great Brassey fortune outright from her mother. In the meantime, she certainly had enough to live well, as they planned, in Kenya. At least for a while.

Joss’s career had so far pursued a curious path. At the age of fifteen he had been expelled from Eton for being caught having sex with a housemaid twice his age. He had then joined his parents in Le Havre, where his father was based, and finished his education there. At eighteen he had slipped straight into the Foreign Office and a posting as private secretary to the British ambassador in Berlin—where his father, Victor, Lord Kilmarnock, had just been posted as chargé d’affaires. Three years later, in 1923, he again followed his father, this time to the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission, situated in the picturesque German town of Koblenz. Idina, not quite divorced, had followed him there.

Victor Kilmarnock was now the British High Commissioner in Koblenz and Joss lived with his parents in the British Residence. This was an appropriately imposing creeper-clad, stone-walled, and fish-scale-tile-roofed building, surrounded by tall trees on the banks of the Rhine. Around it stood half a dozen similar edifices belonging to the French, Dutch, Belgian, and American embassies, whose inhabitants had turned the town into a hive of international social activity: there were boats to row, horses to bet on, a theater with a kaleidoscopic program that made it worth visiting at least once, if not twice, a week, and endless parties.

Idina’s arrival shocked the staff at the Residence.

7

Not only was she much older than Joss but her hair was cut in a boyish “Eton crop”

8

and “Her figure resembled that of a boy, too, very very slim,” said one of the

other guests at the Residence at the time, who thought that Idina and Joss “seemed like brother and sister; there was something alike in them.”

9

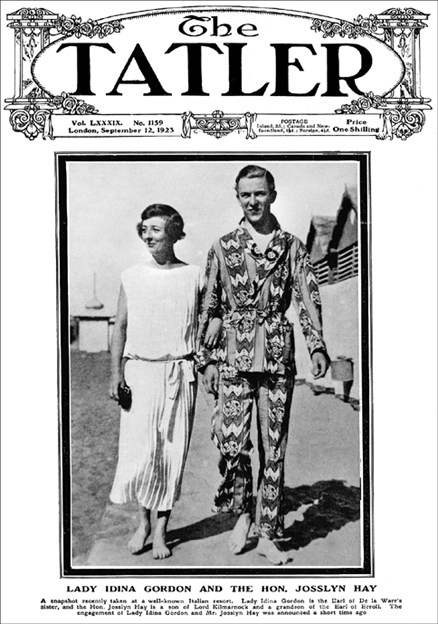

Idina and her third husband, Joss, shortly after their engagement in September 1923. Joss became the 22nd Earl of Erroll

.

And Joss’s behavior went haywire. One evening, while the household was bathing and changing before a reception for Monsieur Tirade, the French High Commissioner, Idina and Joss sneaked downstairs and strung up a line of their own carefully prepared bunting—a long row of bras and knickers dyed red, white, and blue into an enormous tricolor flag. Joss’s father was deeply embarrassed.

10

He “begged Joss not to marry Idina, even making him promise.”

11

At least, Victor Kilmarnock must have comforted himself, Idina would not be around for long. She was openly planning to return to Africa and make a home there.

12

In Koblenz she spent her days hunting down antiques and linens for the house in Kenya and even ordering a vast bath made from green onyx. What Victor Kilmarnock did not realize was that, regardless of promises, she was going to take his son with her.