The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (92 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

12.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

What about domestic violence itself? Before we look at the trends, we have to consider a surprising claim: that men commit no more domestic violence than women. The sociologist Murray Straus has conducted many confidential and anonymous surveys that asked people in relationships whether they had ever used violence against their partners, and he found no difference between the sexes.

81

In 1978 he wrote, “The old cartoons of the wife chasing her husband with a rolling pin or throwing pots and pans are closer to reality than most (and especially those with feminist sympathies) realize.”

82

Some activists have called for greater recognition of the problem of battered men, and for a network of shelters in which men can escape from their violent wives and girlfriends. This would be quite a twist. If women were never the victims of a gendered category of violence called “wife-beating,” but rather both sexes have always been equally victimized by “spouse-beating,” it would be misleading to ask whether wife-beating has declined over time as a part of the campaign to end violence against women.

81

In 1978 he wrote, “The old cartoons of the wife chasing her husband with a rolling pin or throwing pots and pans are closer to reality than most (and especially those with feminist sympathies) realize.”

82

Some activists have called for greater recognition of the problem of battered men, and for a network of shelters in which men can escape from their violent wives and girlfriends. This would be quite a twist. If women were never the victims of a gendered category of violence called “wife-beating,” but rather both sexes have always been equally victimized by “spouse-beating,” it would be misleading to ask whether wife-beating has declined over time as a part of the campaign to end violence against women.

To make sense of the survey findings, one has to be careful about what one means by domestic violence. It turns out that there really is a distinction between common marital spats that escalate into violence (“the conversations with the flying plates,” as Rodgers and Hart put it) and the systematic intimidation and coercion of one partner by another.

83

The sociologist Michael Johnson analyzed data on the interactions between partners in violent relationships and discovered a cluster of controlling tactics that tended to go together. In some couples, one partner threatens the other with force, controls the family finances, restricts the other’s movements, redirects anger and violence against the children or pets, and strategically withholds praise and affection. Among couples with a controller, the controllers who used violence were almost exclusively men; the spouses who used violence were almost entirely women, presumably defending themselves or their children. When neither partner was a controller, violence erupted only when an argument got out of hand, and in those couples the men were just a shade more prone to using force than the women. The distinction between controllers and squabblers, then, resolves the mystery of the genderneutral violence statistics. The numbers in violence surveys are dominated by spats between noncontrolling partners, in which the women give as good as they get. But the numbers from shelter admissions, court records, emergency rooms, and police statistics are dominated by couples with a controller, usually the man intimidating the woman, and occasionally a woman defending herself. The asymmetry is even greater with estranged partners, in which it is the men who do most of the stalking, threatening, and harming. Other studies have confirmed that chronic intimidation, serious violence, and maleness tend to go together.

84

83

The sociologist Michael Johnson analyzed data on the interactions between partners in violent relationships and discovered a cluster of controlling tactics that tended to go together. In some couples, one partner threatens the other with force, controls the family finances, restricts the other’s movements, redirects anger and violence against the children or pets, and strategically withholds praise and affection. Among couples with a controller, the controllers who used violence were almost exclusively men; the spouses who used violence were almost entirely women, presumably defending themselves or their children. When neither partner was a controller, violence erupted only when an argument got out of hand, and in those couples the men were just a shade more prone to using force than the women. The distinction between controllers and squabblers, then, resolves the mystery of the genderneutral violence statistics. The numbers in violence surveys are dominated by spats between noncontrolling partners, in which the women give as good as they get. But the numbers from shelter admissions, court records, emergency rooms, and police statistics are dominated by couples with a controller, usually the man intimidating the woman, and occasionally a woman defending herself. The asymmetry is even greater with estranged partners, in which it is the men who do most of the stalking, threatening, and harming. Other studies have confirmed that chronic intimidation, serious violence, and maleness tend to go together.

84

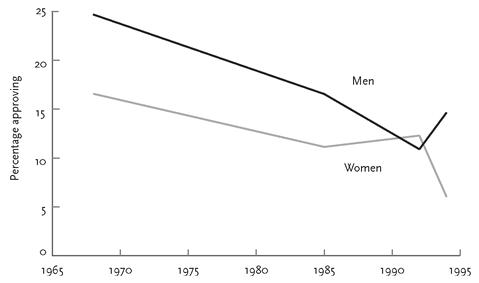

FIGURE 7–12.

Approval of husband slapping wife in the United States, 1968–1994

Approval of husband slapping wife in the United States, 1968–1994

Source:

Graph from Straus et al., 1997.

Graph from Straus et al., 1997.

So has anything changed over time? With the small stuff—the mutual slapping and shoving—perhaps not.

85

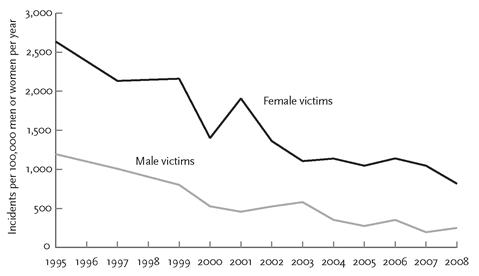

But with violence that is severe enough to count as an assault, so that it turns up in the National Crime Victimization Survey, the rates have plunged. As with estimates of rape, the numbers from a victimization study can’t be treated as exact measures of rates of domestic violence, but they are useful as a measure of trends over time, especially since the new concern over domestic violence should make the recent respondents more willing to report abuse. The Bureau of Justice provides data from 1993 to 2005, which are plotted in figure 7–13. The rate of reported violence against women by their intimate partners has fallen by almost two-thirds, and the rate against men has fallen by almost half.

85

But with violence that is severe enough to count as an assault, so that it turns up in the National Crime Victimization Survey, the rates have plunged. As with estimates of rape, the numbers from a victimization study can’t be treated as exact measures of rates of domestic violence, but they are useful as a measure of trends over time, especially since the new concern over domestic violence should make the recent respondents more willing to report abuse. The Bureau of Justice provides data from 1993 to 2005, which are plotted in figure 7–13. The rate of reported violence against women by their intimate partners has fallen by almost two-thirds, and the rate against men has fallen by almost half.

The decline almost certainly began earlier. In Straus’s surveys, women in 1985 reported twice the number of severe assaults by their husbands as did the women in 1992, the year the federal victimization data begin.

86

86

What about the most extreme form of domestic violence, uxoricide and mariticide? To a social scientist, the killing of one intimate partner by another has the great advantage that one needn’t haggle over definitions or worry about reporting biases: dead is dead. Figure 7–14 shows the rates of killing of intimate partners from 1976 to 2005, expressed as a ratio per 100,000 people of the same sex.

FIGURE 7–13.

Assaults by intimate partners in the United States, 1993–2005

Assaults by intimate partners in the United States, 1993–2005

Source:

Data from U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010.

Data from U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010.

FIGURE 7–14.

Homicides of intimate partners in the United States, 1976–2005

Homicides of intimate partners in the United States, 1976–2005

Sources:

Data from U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011, with adjustments by the

Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online

(

http://www.albany.edu/sourcebook/csv/t31312005.csv

). Population figures from the U.S. Census.

Data from U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011, with adjustments by the

Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online

(

http://www.albany.edu/sourcebook/csv/t31312005.csv

). Population figures from the U.S. Census.

Once again, we see a substantial decline, though with an interesting twist: feminism has been very good for men. In the years since the ascendancy of the women’s movement, the chance that a man would be killed by his wife, ex-wife, or girlfriend has fallen sixfold. Since there was no campaign to end violence against men during this period, and since women in general are the less homicidal sex, the likeliest explanation is that a woman was apt to kill an abusive husband or boyfriend when he threatened to harm her if she left him. The advent of women’s shelters and restraining orders gave women an escape plan that was a bit less extreme.

87

87

What about the rest of the world? Unfortunately it is not easy to tell. Unlike homicide, definitions of rape and spousal abuse are all over the map, and police records are misleading because any change in the rate of violence against women can be swamped by changes in the willingness of women to report the abuse to the police. Adding to the confusion, advocacy groups tend to inflate statistics on rates of violence against women and to hide statistics on trends over time. The U.K. Home Office administers a crime victimization survey in England and Wales, but it does not present data on trends in rape or domestic violence.

88

But when the data from separate annual reports are aggregated, as in figure 7–15, they show a dramatic decline in domestic violence, similar to the one seen in the United States. Because of differences in how domestic violence is defined and how population bases are tabulated, the numbers in this graph are not commensurable with those of figure 7–13, but the trends over time are almost the same. It is safe to guess that similar declines have taken place in other Western democracies, because domestic violence has been a concern in all of them.

88

But when the data from separate annual reports are aggregated, as in figure 7–15, they show a dramatic decline in domestic violence, similar to the one seen in the United States. Because of differences in how domestic violence is defined and how population bases are tabulated, the numbers in this graph are not commensurable with those of figure 7–13, but the trends over time are almost the same. It is safe to guess that similar declines have taken place in other Western democracies, because domestic violence has been a concern in all of them.

FIGURE 7–15.

Domestic violence in England and Wales, 1995–2008

Domestic violence in England and Wales, 1995–2008

Sources:

Data from British Crime Survey, U.K., Home Office, 2010. Data aggregated across years by Dewar Research, 2009. Population estimates from the U.K. Office for National Statistics, 2009.

Data from British Crime Survey, U.K., Home Office, 2010. Data aggregated across years by Dewar Research, 2009. Population estimates from the U.K. Office for National Statistics, 2009.

Though the United States and other Western nations are often accused of being misogynistic patriarchies, the rest of the world is immensely worse. As I mentioned, surveys of domestic violence in the United States that are broad enough to include minor acts of shoving and slapping show no difference between men and women; the same is true of Canada, Finland, Germany, the U.K., Ireland, Israel, and Poland. But that gender neutrality is a departure from the rest of the world. The psychologist John Archer looked at sex ratios in surveys of domestic violence in sixteen countries and found that in the non-Western ones—India, Jordan, Japan, Korea, Nigeria, and Papua New Guinea—the men do more of the hitting.

89

89

The World Health Organization recently published a hodgepodge of rates of serious domestic violence from forty-eight countries.

90

Worldwide, it has been estimated that between a fifth and a half of all women have been victims of domestic violence, and they are far worse off in countries outside Western Europe and the Anglosphere.

91

In the United States, Canada, and Australia, fewer than 3 percent of women report that their partners assaulted them in the previous year, but the reports from other countries are an order of magnitude higher: 27 percent in a Nicaraguan sample, 38 percent in a Korean sample, and 52 percent in a Palestinian sample. Attitudes toward marital violence also show striking differences. About 1 percent of New Zealanders and 4 percent of Singaporeans say that a husband has the right to beat a wife who talks back or disobeys him. But the figures are 78 percent for rural Egyptians, up to 50 percent for Indians in Uttar Pradesh, and 57 percent for Palestinians.

90

Worldwide, it has been estimated that between a fifth and a half of all women have been victims of domestic violence, and they are far worse off in countries outside Western Europe and the Anglosphere.

91

In the United States, Canada, and Australia, fewer than 3 percent of women report that their partners assaulted them in the previous year, but the reports from other countries are an order of magnitude higher: 27 percent in a Nicaraguan sample, 38 percent in a Korean sample, and 52 percent in a Palestinian sample. Attitudes toward marital violence also show striking differences. About 1 percent of New Zealanders and 4 percent of Singaporeans say that a husband has the right to beat a wife who talks back or disobeys him. But the figures are 78 percent for rural Egyptians, up to 50 percent for Indians in Uttar Pradesh, and 57 percent for Palestinians.

Laws on violence against women also show a lag from the legal reforms of W estern democracies.

92

Eighty-four percent of the countries of Western Europe have outlawed or are planning to outlaw domestic violence, and 72 percent have done so for marital rape. Here are the respective figures for other parts of the world: Eastern Europe, 57 and 39 percent; Asia and the Pacific, 51 and 19 percent; Latin America, 94 and 18 percent; sub-Saharan Africa, 35 and 12.5 percent; Arab states, 25 and 0 percent. On top of these injustices, sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southwest Asia are host to systematic atrocities against women that are rare or unheard of in the 21st-century West, including infanticide, genital mutilation, trafficking in child prostitutes and sex slaves, honor killings, attacks on disobedient or under-dowried wives with acid and burning kerosene, and mass rapes during wars, riots, and genocides.

93

92

Eighty-four percent of the countries of Western Europe have outlawed or are planning to outlaw domestic violence, and 72 percent have done so for marital rape. Here are the respective figures for other parts of the world: Eastern Europe, 57 and 39 percent; Asia and the Pacific, 51 and 19 percent; Latin America, 94 and 18 percent; sub-Saharan Africa, 35 and 12.5 percent; Arab states, 25 and 0 percent. On top of these injustices, sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southwest Asia are host to systematic atrocities against women that are rare or unheard of in the 21st-century West, including infanticide, genital mutilation, trafficking in child prostitutes and sex slaves, honor killings, attacks on disobedient or under-dowried wives with acid and burning kerosene, and mass rapes during wars, riots, and genocides.

93

Other books

Fallen Angel (Hqn) by Bradley, Eden

Harvest of Hearts by Laura Hilton

Bear Down: BBW Paranormal Shape Shifter Romance by Terra Wolf, Alannah Blacke

Memory Lapse: A Slater Vance Novel by Potter, LR

In Too Deep by Grant, D C

Love Beyond Expectations by Rebecca Royce

Changeling Moon by Dani Harper

The Shoe Princess's Guide to the Galaxy by Emma Bowd

Snowman's Chance in Hell by Robert T. Jeschonek

Sorrow Without End by Priscilla Royal