The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (44 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

13.47Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

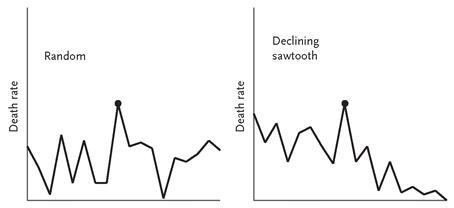

FIGURE 5–1.

Two pessimistic possibilities for historical trends in war

Two pessimistic possibilities for historical trends in war

FIGURE 5–2.

Two less pessimistic possibilities for historical trends in war

Two less pessimistic possibilities for historical trends in war

The right-hand panel in figure 5–2 places the war in a narrative that is so unpessimistic that it’s almost optimistic. Could World War II be an isolated peak in a declining sawtooth—the last gasp in a long slide of major war into historical obsolescence? Again, we will see that this possibility is not as dreamy as it sounds.

The long-term trajectory of war, in reality, is likely to be a superimposition of several trends. We all know that patterns in other complex sequences, such as the weather, are a composite of several curves: the cyclical rhythm of the seasons, the randomness of daily fluctuations, the long-term trend of global warming. The goal of this chapter is to identify the components of the long-term trends in wars between states. I will try to persuade you that they are as follows:

• No cycles.

• A big dose of randomness.

• An escalation, recently reversed, in the destructiveness of war.

• Declines in every other dimension of war, and thus in interstate war as a whole.

The 20th century, then, was not a permanent plunge into depravity. On the contrary, the enduring moral trend of the century was a violence-averse humanism that originated in the Enlightenment, became overshadowed by counter-Enlightenment ideologies wedded to agents of growing destructive power, and regained momentum in the wake of World War II.

To reach these conclusions, I will blend the two ways of understanding the trajectory of war: the statistics of Richardson and his heirs, and the narratives of traditional historians and political scientists. The statistical approach is necessary to avoid Toynbee’s fallacy: the all-too-human tendency to hallucinate grand patterns in complex statistical phenomena and confidently extrapolate them into the future. But if narratives without statistics are blind, statistics without narratives are empty. History is not a screen saver with pretty curves generated by equations; the curves are abstractions over real events involving the decisions of people and the effects of their weapons. So we also need to explain how the various staircases, ramps, and sawtooths we see in the graphs emerge from the behavior of leaders, soldiers, bayonets, and bombs. In the course of the chapter, the ingredients of the blend will shift from the statistical to the narrative, but neither is dispensable in understanding something as complex as the long-term trajectory of war.

WAS THE 20th CENTURY REALLY THE WORST?“The twentieth century was the bloodiest in history” is a cliché that has been used to indict a vast range of demons, including atheism, Darwin, government, science, capitalism, communism, the ideal of progress, and the male gender. But is it true? The claim is rarely backed up by numbers from any century other than the 20th, or by a mention of the hemoclysms of centuries past. The truth is that we will never really know which was the worst century, because it’s hard enough to pin down death tolls in the 20th century, let alone earlier ones. But there are two reasons to suspect that the bloodiest-century factoid is an illusion.

The first is that while the 20th century certainly had more violent deaths than earlier ones, it also had more people. The population of the world in 1950 was 2.5 billion, which is about two and a half times the population in 1800, four and a half times that in 1600, seven times that in 1300, and fifteen times that of 1 CE. So the death count of a war in 1600, for instance, would have to be multiplied by 4.5 for us to compare its destructiveness to those in the middle of the 20th century.

9

9

The second illusion is

historical myopia:

the closer an era is to our vantage point in the present, the more details we can make out. Historical myopia can afflict both common sense and professional history. The cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have shown that people intuitively estimate relative frequency using a shortcut called the availability heuristic: the easier it is to recall examples of an event, the more probable people think it is.

10

People, for example, overestimate the likelihoods of the kinds of accidents that make headlines, such as plane crashes, shark attacks, and terrorist bombings, and they underestimate those that pile up unremarked, like electrocutions, falls, and drownings.

11

When we are judging the density of killings in different centuries, anyone who doesn’t consult the numbers is apt to overweight the conflicts that are most recent, most studied, or most sermonized. In a survey of historical memory, I asked a hundred Internet users to write down as many wars as they could remember in five minutes. The responses were heavily weighted toward the world wars, wars fought by the United States, and wars close to the present. Though the earlier centuries, as we shall see, had far more wars, people

remembered

more wars from the recent centuries.

historical myopia:

the closer an era is to our vantage point in the present, the more details we can make out. Historical myopia can afflict both common sense and professional history. The cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have shown that people intuitively estimate relative frequency using a shortcut called the availability heuristic: the easier it is to recall examples of an event, the more probable people think it is.

10

People, for example, overestimate the likelihoods of the kinds of accidents that make headlines, such as plane crashes, shark attacks, and terrorist bombings, and they underestimate those that pile up unremarked, like electrocutions, falls, and drownings.

11

When we are judging the density of killings in different centuries, anyone who doesn’t consult the numbers is apt to overweight the conflicts that are most recent, most studied, or most sermonized. In a survey of historical memory, I asked a hundred Internet users to write down as many wars as they could remember in five minutes. The responses were heavily weighted toward the world wars, wars fought by the United States, and wars close to the present. Though the earlier centuries, as we shall see, had far more wars, people

remembered

more wars from the recent centuries.

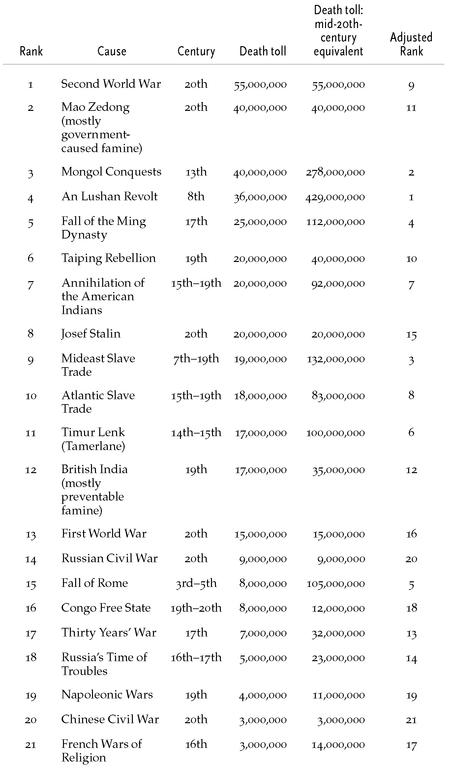

When one corrects for the availability bias and the 20th-century population explosion by rooting around in history books and scaling the death tolls by the world population at the time, one comes across many wars and massacres that could hold their head high among 20th-century atrocities. The table on page 195 is a list from White called “(Possibly) The Twenty (or so) Worst Things People Have Done to Each Other.”

12

Each death toll is the median or mode of the figures cited in a large number of histories and encyclopedias. They include not just deaths on the battlefield but indirect deaths of civilians from starvation and disease; they are thus considerably higher than estimates of battlefield casualties, though consistently so for both recent and ancient events. I have added two columns that scale the death tolls and adjust the rankings to what they would be if the world at the time had had the population it did in the middle of the 20th century.

12

Each death toll is the median or mode of the figures cited in a large number of histories and encyclopedias. They include not just deaths on the battlefield but indirect deaths of civilians from starvation and disease; they are thus considerably higher than estimates of battlefield casualties, though consistently so for both recent and ancient events. I have added two columns that scale the death tolls and adjust the rankings to what they would be if the world at the time had had the population it did in the middle of the 20th century.

First of all: had you even heard of all of them? (I hadn’t.) Second, did you know there were five wars and four atrocities before World War I that killed more people than that war? I suspect many readers will also be surprised to learn that of the twenty-one worst things that people have ever done to each other (that we know of), fourteen were in centuries before the 20th. And all this pertains to absolute numbers. When you scale by population size, only one of the 20th century’s atrocities even makes the top ten. The worst atrocity of all time was the An Lushan Revolt and Civil War, an eight-year rebellion during China’s Tang Dynasty that, according to censuses, resulted in the loss of two-thirds of the empire’s population, a sixth of the world’s population at the time.

13

13

These figures, of course, cannot all be taken at face value. Some tendentiously blame the entire death toll of a famine or epidemic on a particular war, rebellion, or tyrant. And some came from innumerate cultures that lacked modern techniques for counting and record-keeping. At the same time, narrative history confirms that earlier civilizations were certainly capable of killing in vast numbers. Technological backwardness was no impediment; we know from Rwanda and Cambodia that massive numbers of people can be murdered with low-tech means like machetes and starvation. And in the distant past, implements of killing were not always so low-tech, because military weaponry usually boasted the most advanced technology of the age. The military historian John Keegan notes that by the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, the chariot allowed nomadic armies to rain death on the civilizations they invaded. “Circling at a distance of 100 or 200 yards from the herds of unarmored foot soldiers, a chariot crew—one to drive, one to shoot—might have transfixed six men a minute. Ten minutes’ work by ten chariots would cause 500 casualties or more, a Battle of the Somme–like toll among the small armies of the period.”

14

14

High-throughput massacre was also perfected by mounted hordes from the steppes, such as the Scythians, Huns, Mongols, Turks, Magyars, Tatars, Mughals, and Manchus. For two thousand years these warriors deployed meticulously crafted composite bows (made from a glued laminate of wood, tendon, and horn) to run up immense body counts in their sackings and raids. These tribes were responsible for numbers 3, 5, 11, and 15 on the top-twenty-one list, and they take four of the top six slots in the population-adjusted ranking. The Mongol invasions of Islamic lands in the 13th century resulted in the massacre of 1.3 million people in the city of Merv alone, and another 800,000 residents of Baghdad. As the historian of the Mongols J. J. Saunders remarks:

There is something indescribably revolting in the cold savagery with which the Mongols carried out their massacres. The inhabitants of a doomed town were obliged to assemble in a plain outside the walls, and each Mongol trooper, armed with a battle-axe, was told to kill so many people, ten, twenty or fifty. As proof that orders had been properly obeyed, the killers were sometimes required to cut off an ear from each victim, collect the ears in sacks, and bring them to their officers to be counted. A few days after the massacre, troops were sent back into the ruined city to search for any poor wretches who might be hiding in holes or cellars; these were dragged out and slain.

15

The Mongols’ first leader, Genghis Khan, offered this reflection on the pleasures of life: “The greatest joy a man can know is to conquer his enemies and drive them before him. To ride their horses and take away their possessions. To see the faces of those who were dear to them bedewed with tears, and to clasp their wives and daughters in his arms.”

16

Modern genetics has shown this was no idle boast. Today 8 percent of the men who live within the former territory of the Mongol Empire share a Y chromosome that dates to around the time of Genghis, most likely because they descended from him and his sons and the vast number of women they clasped in their arms.

17

These accomplishments set the bar pretty high, but Timur Lenk (aka Tamerlane), a Turk who aimed to restore the Mongol Empire, did his best. He slaughtered tens of thousands of prisoners in each of his conquests of western Asian cities, then marked his accomplishment by building minarets out of their skulls. One Syrian eyewitness counted twenty-eight towers of fifteen hundred heads apiece.

18

16

Modern genetics has shown this was no idle boast. Today 8 percent of the men who live within the former territory of the Mongol Empire share a Y chromosome that dates to around the time of Genghis, most likely because they descended from him and his sons and the vast number of women they clasped in their arms.

17

These accomplishments set the bar pretty high, but Timur Lenk (aka Tamerlane), a Turk who aimed to restore the Mongol Empire, did his best. He slaughtered tens of thousands of prisoners in each of his conquests of western Asian cities, then marked his accomplishment by building minarets out of their skulls. One Syrian eyewitness counted twenty-eight towers of fifteen hundred heads apiece.

18

The worst-things list also gives the lie to the conventional wisdom that the 20th century saw a quantum leap in organized violence from a peaceful 19th. For one thing, the 19th century has to be gerrymandered to show such a leap by chopping off the extremely destructive Napoleonic Wars from its beginning. For another, the lull in war in the remainder of the century applies only to Europe. Elsewhere we find many hemoclysms, including the Taiping Rebellion in China (a religiously inspired revolt that was perhaps the worst civil war in history), the African slave trade, imperial wars throughout Asia, Africa, and the South Pacific, and two major bloodlettings that didn’t even make the list: the American Civil War (650,000 deaths) and the reign of Shaka, a Zulu Hitler who killed between 1 and 2 million people during his conquest of southern Africa between 1816 and 1827. Did I leave any continent out? Oh yes, South America. Among its many wars is the War of the Triple Alliance, which may have killed 400,000 people, including more than 60 percent of the population of Paraguay, making it proportionally the most destructive war in modern times.

A list of extreme cases, of course, cannot establish a trend. There were more major wars and massacres before the 20th century, but then there were more centuries before the 20th. Figure 5–3 extends White’s list from the top twenty-one to the top hundred, scales them by the population of the world in that era, and shows how they were distributed in time between 500 BCE and 2000 CE.

Other books

A Handful of Time by Kit Pearson

The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes

Without Light or Guide by T. Frohock

Mine by Brett Battles

Negative by Viola Grace

The Texans by Brett Cogburn

Lorik The Protector (Lorik Trilogy) by Toby Neighbors

Thomas Covenant 03: Power That Preserves by Stephen R. Donaldson

Rufus M. by Eleanor Estes