The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (45 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

7.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

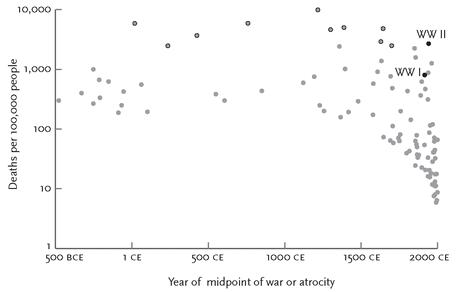

FIGURE 5–3.

100 worst wars and atrocities in human history

100 worst wars and atrocities in human history

Source:

Data from White, in press, scaled by world population from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, at the midpoint of the listed range. Note that the estimates are not scaled by the duration of the war or atrocity. Circled dots represent selected events with death rates higher than the 20th-century world wars (from earlier to later): Xin Dynasty, Three Kingdoms, fall of Rome, An Lushan Revolt, Genghis Khan, Mideast slave trade, Timur Lenk, Atlantic slave trade, fall of the Ming Dynasty, and the conquest of the Americas.

Data from White, in press, scaled by world population from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, at the midpoint of the listed range. Note that the estimates are not scaled by the duration of the war or atrocity. Circled dots represent selected events with death rates higher than the 20th-century world wars (from earlier to later): Xin Dynasty, Three Kingdoms, fall of Rome, An Lushan Revolt, Genghis Khan, Mideast slave trade, Timur Lenk, Atlantic slave trade, fall of the Ming Dynasty, and the conquest of the Americas.

Two patterns jump out of the splatter. The first is that the most serious wars and atrocities—those that killed more than a tenth of a percent of the population of the world—are pretty evenly distributed over 2,500 years of history. The other is that the cloud of data tapers rightward and downward into smaller and smaller conflicts for years that are closer to the present. How can we explain this funnel? It’s unlikely that our distant ancestors refrained from small massacres and indulged only in large ones. White offers a more likely explanation:

Maybe the only reason it appears that so many were killed in the past 200 years is because we have more records from that period. I’ve been researching this for years, and it’s been a long time since I found a new, previously unpublicized mass killing from the Twentieth Century; however, it seems like every time I open an old book, I will find another hundred thousand forgotten people killed somewhere in the distant past. Perhaps one chronicler made a note long ago of the number killed, but now that event has faded into the forgotten past. Maybe a few modern historians have revisited the event, but they ignore the body count because it doesn’t fit into their perception of the past. They don’t believe it was possible to kill that many people without gas chambers and machine guns so they dismiss contrary evidence as unreliable.

19

And of course for every massacre that was recorded by some chronicler and then overlooked or dismissed, there must have been many others that were never chronicled in the first place.

A failure to adjust for this historical myopia can lead even historical scholars to misleading conclusions. William Eckhardt assembled a list of wars going back to 3000 BCE and plotted their death tolls against time.

20

His graph showed an acceleration in the rate of death from warfare over five millennia, picking up steam after the 16th century and blasting off in the 20th.

21

But this hockey stick is almost certainly an illusion. As James Payne has noted, any study that claims to show an increase in wars over time without correcting for historical myopia only shows that “the Associated Press is a more comprehensive source of information about battles around the world than were sixteenth-century monks.”

22

Payne showed that this problem is genuine, not just hypothetical, by looking at one of Eckhardt’s sources, Quincy Wright’s monumental

A Study of War

, which has a list of wars from 1400 to 1940. Wright had been able to nail down the starting and ending month of 99 percent of the wars between 1875 to 1940, but only 13 percent of the wars between 1480 and 1650, a telltale sign that records of the distant past are far less complete than those of the recent past.

23

20

His graph showed an acceleration in the rate of death from warfare over five millennia, picking up steam after the 16th century and blasting off in the 20th.

21

But this hockey stick is almost certainly an illusion. As James Payne has noted, any study that claims to show an increase in wars over time without correcting for historical myopia only shows that “the Associated Press is a more comprehensive source of information about battles around the world than were sixteenth-century monks.”

22

Payne showed that this problem is genuine, not just hypothetical, by looking at one of Eckhardt’s sources, Quincy Wright’s monumental

A Study of War

, which has a list of wars from 1400 to 1940. Wright had been able to nail down the starting and ending month of 99 percent of the wars between 1875 to 1940, but only 13 percent of the wars between 1480 and 1650, a telltale sign that records of the distant past are far less complete than those of the recent past.

23

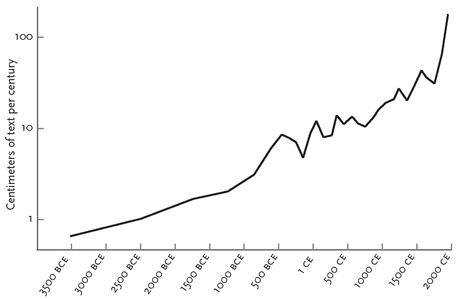

The historian Rein Taagepera quantified the myopia in a different way. He took a historical almanac and stepped through the pages with a ruler, measuring the number of column inches devoted to each century.

24

The range was so great that he had to plot the data on a logarithmic scale (on which an exponential fade looks like a straight line). His graph, reproduced in figure 5–4, shows that as you go back into the past, historical coverage hurtles exponentially downward for two and a half centuries, then falls with a gentler but still exponential decline for the three millennia before.

24

The range was so great that he had to plot the data on a logarithmic scale (on which an exponential fade looks like a straight line). His graph, reproduced in figure 5–4, shows that as you go back into the past, historical coverage hurtles exponentially downward for two and a half centuries, then falls with a gentler but still exponential decline for the three millennia before.

If it were only a matter of missing a few small wars that escaped the notice of ancient chroniclers, one might be reassured that the body counts were not underestimated, because most of the deaths would be in big wars that no one could fail to notice. But the undercounting may introduce a bias, not just a fuzziness, in the estimates. Keegan writes of a “military horizon.”

25

Beneath it are the raids, ambushes, skirmishes, turf battles, feuds, and depredations that historians dismiss as “primitive” warfare. Above it are the organized campaigns for conquest and occupation, including the set-piece battles that war buffs reenact in costume or display with toy soldiers. Remember Tuchman’s “private wars” of the 14th century, the ones that knights fought with furious gusto and a single strategy, namely killing as many of another knight’s peasants as possible? Many of these massacres were never dubbed The War of Such-and-Such and immortalized in the history books. An undercounting of conflicts below the military horizon could, in theory, throw off the body count for the period as a whole. If more conflicts fell beneath the military horizon in the anarchic feudal societies, frontiers, and tribal lands of the early periods than in the clashes between Leviathans of the later ones, then the earlier periods would appear less violent to us than they really were.

25

Beneath it are the raids, ambushes, skirmishes, turf battles, feuds, and depredations that historians dismiss as “primitive” warfare. Above it are the organized campaigns for conquest and occupation, including the set-piece battles that war buffs reenact in costume or display with toy soldiers. Remember Tuchman’s “private wars” of the 14th century, the ones that knights fought with furious gusto and a single strategy, namely killing as many of another knight’s peasants as possible? Many of these massacres were never dubbed The War of Such-and-Such and immortalized in the history books. An undercounting of conflicts below the military horizon could, in theory, throw off the body count for the period as a whole. If more conflicts fell beneath the military horizon in the anarchic feudal societies, frontiers, and tribal lands of the early periods than in the clashes between Leviathans of the later ones, then the earlier periods would appear less violent to us than they really were.

FIGURE 5–4.

Historical myopia: Centimeters of text per century in a historical almanac

Historical myopia: Centimeters of text per century in a historical almanac

Source:

Data from Taagepera & Colby, 1979, p. 911.

Data from Taagepera & Colby, 1979, p. 911.

So when one adjusts for population size, the availability bias, and historical myopia, it is far from clear that the 20th century was the bloodiest in history. Sweeping that dogma out of the way is the first step in understanding the historical trajectory of war. The next is to zoom in for a closer look at the distribution of wars over time—which holds even more surprises.

THE STATISTICS OF DEADLY QUARRELS, PART 1: THE TIMING OF WARSLewis Richardson wrote that his quest to analyze peace with numbers sprang from two prejudices. As a Quaker, he believed that “the moral evil in war outweighs the moral good, although the latter is conspicuous.”

26

As a scientist, he thought there was too much moralizing about war and not enough knowledge: “For indignation is so easy and satisfying a mood that it is apt to prevent one from attending to any facts that oppose it. If the reader should object that I have abandoned ethics for the false doctrine that ‘tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner’ [to understand all is to forgive all], I can reply that it is only a temporary suspense of ethical judgment, made because ‘beaucoup condamner c’est peu comprendre’ [to condemn much is to understand little].”

27

26

As a scientist, he thought there was too much moralizing about war and not enough knowledge: “For indignation is so easy and satisfying a mood that it is apt to prevent one from attending to any facts that oppose it. If the reader should object that I have abandoned ethics for the false doctrine that ‘tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner’ [to understand all is to forgive all], I can reply that it is only a temporary suspense of ethical judgment, made because ‘beaucoup condamner c’est peu comprendre’ [to condemn much is to understand little].”

27

After poring through encyclopedias and histories of different regions of the world, Richardson compiled data on 315 “deadly quarrels” that ended between 1820 and 1952. He faced some daunting problems. One is that most histories are sketchy when it comes to numbers. Another is that it isn’t always clear how to count wars, since they tend to split, coalesce, and flicker on and off. Is World War II a single war or two wars, one in Europe and the other in the Pacific? If it’s a single war, should we not say that it began in 1937, with Japan’s full-scale invasion of China, or even in 1931, when it occupied Manchuria, rather than the conventional starting date of 1939? “The concept of a war as a discrete thing does not fit the facts,” he observed. “Thinginess fails.”

28

28

Thinginess failures are familiar to physicists, and Richardson handled them with two techniques of mathematical estimation. Rather than seeking an elusive “precise definition” of a war, he gave the average priority over the individual case: as he considered each unclear conflict in turn, he systematically flipped back and forth between lumping them into one quarrel and splitting them into two, figuring that the errors would cancel out in the long run. (It’s the same principle that underlies the practice of rounding a number ending in 5 to the closest even digit—half the time it will go up, half the time down.) And borrowing a practice from astronomy, Richardson assigned each quarrel a magnitude, namely the base-ten logarithm (roughly, the number of zeroes) of the war’s death toll. On a logarithmic scale, a certain degree of imprecision in the measurements doesn’t matter as much as it does on a conventional linear scale. For example, uncertainty over whether a war killed 100,000 or 200,000 people translates to an uncertainty in magnitude of only 5 versus 5.3. So Richardson sorted the magnitudes into logarithmic pigeonholes: 2.5 to 3.5 (that is, between 316 and 3,162 deaths), 3.5 to 4.5 (3,163 to 31,622), and so on. The other advantage of a logarithmic scale is that it allows us to visualize quarrels of a variety of sizes, from turf battles to world wars, on a single scale.

Richardson also faced the problem of what kinds of quarrels to include, which deaths to tally, and how low to go. His criterion for adding a historical event to his database was “malice aforethought,” so he included wars of all kinds and sizes, as well as mutinies, insurrections, lethal riots, and genocides; that’s why he called his units of analysis “deadly quarrels” instead of haggling over what really deserves the word “war.” His magnitude figures included soldiers killed on the battlefield, civilians killed deliberately or as collateral damage, and deaths of soldiers from disease or exposure; he did not count civilian deaths from disease or exposure since these are more properly attributed to negligence than to malice.

Richardson bemoaned an important gap in the historical record: the feuds, raids, and skirmishes that killed between 4 and 315 people apiece (magnitude 0.5 to 2.5), which were too big for criminologists to record but too small for historians. He illustrated the problem of these quarrels beneath the military horizon by quoting from Reginald Coupland’s history of the East African slave trade:

“The main sources of supply were the organized slave-raids in the chosen areas, which shifted steadily inland as tract after tract became ‘worked out.’ The Arabs might conduct a raid themselves, but more usually they incited a chief to attack another tribe, lending him their own armed slaves and guns to ensure his victory. The result, of course, was an increase in intertribal warfare till ‘the whole country was in a flame.’ ”How should this abominable custom be classified? Was it all one huge war between Arabs and Negroes which began two thousand years before it ended in 1880? If so it may have caused more deaths than any other war in history. From Coupland’s description, however, it would seem more reasonable to regard slave-raiding as a numerous collection of small fatal quarrels each between an Arab caravan and a negro tribe or village, and of magnitudes such as 1, 2, or 3. Detailed statistics are not available.

29

Nor were they available for 80 revolutions in Latin America, 556 peasant uprisings in Russia, and 477 conflicts in China, which Richardson knew about but was forced to exclude from his tallies.

30

30

Richardson did, however, anchor the scale at magnitude 0 by including statistics on homicides, which are quarrels with a death toll of 1 (since 10° = 1). He anticipates an objection by Shakespeare’s Portia: “You ought not to mix up murder with war; for murder is an abominable selfish crime, but war is a heroic and patriotic adventure.” He replies: “Yet they are both fatal quarrels. Does it never strike you as puzzling that it is wicked to kill one person, but glorious to kill ten thousand?”

31

31

Richardson then analyzed the 315 quarrels (without the benefit of a computer) to get a bird’s-eye view of human violence and test a variety of hypotheses suggested by historians and his own prejudices.

32

Most of the hypotheses did not survive their confrontation with the data. A common language didn’t make two factions less likely to go to war (just think of most civil wars, or the 19th-century wars between South American countries); so much for the “hope” that gave Esperanto its name. Economic indicators predicted little; rich countries, for example, didn’t systematically pick on poor countries or vice versa. Wars were not, in general, precipitated by arms races.

32

Most of the hypotheses did not survive their confrontation with the data. A common language didn’t make two factions less likely to go to war (just think of most civil wars, or the 19th-century wars between South American countries); so much for the “hope” that gave Esperanto its name. Economic indicators predicted little; rich countries, for example, didn’t systematically pick on poor countries or vice versa. Wars were not, in general, precipitated by arms races.

Other books

Underneath by Andie M. Long

THE SPIDER-City of Doom by Norvell W. Page

The Science Officer by Blaze Ward

Beneath a Darkening Moon by Keri Arthur

The Mask of Atreus by A. J. Hartley

Latidos mortales by Jim Butcher

Sam (BBW Bear Shifter Wedding Romance) (Grizzly Groomsmen Book 2) by Becca Fanning

Above the East China Sea: A Novel by Sarah Bird

Pure Heart: Anything for You Series - Book 1 by Wynn, Ann

Blood Tears by Michael J. Malone