The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (13 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

Patton's men counterattacked a few minutes later, and “although I had to retire a little, they gained no material advantages,” reported Oley. However, the colonel lost another company commander during this counterattack. Captain William H.H. Parker, who commanded Company H of the 8

th

West Virginia, was wounded and captured when Oley was forced to leave the wounded officer on the field.

232

Averell also ordered the 3

rd

West Virginia and 14

th

Pennsylvania to come up and deploy, but it took time for them to do so with the column strung out in a narrow gorge for four miles.

233

The inevitable delay of the deployment of the 3

rd

West Virginia and 14

th

Pennsylvania meant that Ewing's guns did not have as much support as they should have had. When Edgar's battalion attacked, “the Second on the right, and the Eighth on the left, afforded some support, but Ewing's battery, with canister, not only resisted the approach of the enemy, but actually advanced upon him, in order to obtain a better position,” reported Averell, “and held him at bay until the arrival” of the 14

th

Pennsylvania and 3

rd

West Virginia, which were immediately deployed on the right and left of the turnpike, plugging the gap in Averell's line.

234

The 14

th

Pennsylvania held the right end of Averell's line, with its Company A anchoring the far right flank of the Union line.

235

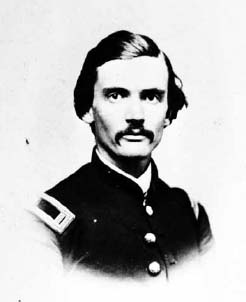

Lieutenant Howard Morton, who assumed command of Ewing's battery after Ewing was severely wounded in combat.

Ronnie Tront

.

Ewing was searching for a better position for his guns when he came under fire. Averell arrived at the front just in time to see Ewing fall, badly hurt. “I saw him fall desperately wounded in the thigh or hip, with great fortitude he kept his place, that is, continued for some time to direct the operations of his gunners until the onset of the enemy was repelled,” recalled General Averell.

236

Adam Brown, who served under Ewing, was also desperately wounded at Ewing's side during this vicious exchange, eventually losing an arm to his injury.

237

The unconscious Ewing was carried from the field, and the battery's senior lieutenant, twenty-one-year-old Howard Morton, took command.

238

Morton, described as “a brave officer and thoroughly qualified for the position he held,” handled the battery with skill and aplomb for the rest of the engagement.

239

Morton's two guns wreaked such havoc on Chapman's battery that Chapman galloped up to Sergeant John G. Stevens, who commanded one of his guns, and asked, “That cannon is tearing us all to pieces; can't you do something?”

“I do not know where they are,” replied Stevens.

“Turn around and fire there on the mountain,” responded Chapman, “and make them think you know where they are.” Stevens yanked the lanyard and a shot belched forth from his gun. The Union gun did not respond, largely because its tube had burst at the muzzle.

240

Richard Minner of Chapman's Battery was lying behind a tree stump when a piece of Union shrapnel ripped into his thigh, badly shattering the leg and severing the femoral artery. Minner lay in a pool of his own blood. Stevens saw the injured soldier and, at great risk to his own life, went to Minner and carried him to safety in the rear under heavy fire. Unfortunately, Minner was mortally wounded, and the Southern surgeons could only ease his pain until he died.

241

When Lieutenant Morton ordered the two Union cannons to relocate, Chapman's guns threw shells and canister at them, spooking the battery horses, which reared and broke the pole of one of the guns. That, in turn, drove the cannon off the road, and then the limber got hung up on a stump, stranding the gun there. A sergeant ordered the drivers to turn their horses and pull the gun back on the road, which they did with serious loss while taking heavy fire from Chapman's guns. A new pole was inserted into the gun, and it soon went back into action, once more belching fire at the Confederates.

242

Repulsed by the severe fire of Morton's two guns, Edgar's men retreated to their barricade. “The enemy gave away his position to us, and endeavored to assume another about half a mile in rear of the first, with his right resting upon a rugged prominence, his center and left protected by a temporary stockade, which he had formed of fence-rails,” stated Averell. “I resolved to dislodge him before he should become well established, and then, if possible, to rout him from the field.”

243

When Edgar's battalion fell back, the 2

nd

West Virginia and 14

th

Pennsylvania Cavalry attacked. The ground over which the 14

th

Pennsylvania attacked had recently been timbered, and tree trunks and limbs still littered the field, severely impeding their advance.

244

Their charge failed to drive Edgar's determined defenders from their barricade, and the blunted Federals fell back to a grove of sugar maples. Lieutenant Alexander Pentecost, the quartermaster of the 2

nd

West Virginia, retreated and found himself alone near a maple tree. Pentecost stood there, oblivious to the danger, until some of his comrades called out to him. Pentecost could not make out what they were saying but, on looking at the barricade, figured it out: one of Edgar's men was drawing a bead on him. The Southerner had squeezed off several shots at Pentecost, all of which had missed and caused pieces of bark from the maple tree to fall on the lieutenant. The quartermaster beat a hasty and safe retreat.

245

The dismounted troopers of the 14

th

Pennsylvania held the middle of the Federal line. During a full day of stubborn fighting, the Keystone Staters advanced about three hundred yards, but that was it. “The rebel infantry charged the 14

th

three times with fixed bayonets,” remembered the regimental historian, “but the 14

th

met them and their bayonets with drawn sabers and three times drove them back.”

246

As the guns of both sides belched death, Patton's brigade completed its deployment. Five companies of the 22

nd

VirginiaâCompanies A, B, E, G and Hâunder command of Lieutenant Colonel Andrew R. Barbee, advanced to a fence running across a gentle ascent of open ground, and five more deployed as skirmishers to take possession of a thickly wooded hill to the right of the Miller house, connecting on the right with Edgar's skirmishers. “The skirmishing companies soon became hotly engaged, holding their ground for some time, stubbornly resisting and beating back the enemy until, being attacked by a much superior force, they were compelled to fall back on the line.”

247

The Confederates hastily threw up their crude barricade of fence rails across the road and bottom to a steep, wooded hill on their right where Major Richard Woodram, with three companies of the 26

th

Virginia, had been posted to observe the enemy's movements in that direction.

248

“The Federals had a decided advantage in position, and the Confederates were going double-quickâ¦when the Federals reached there and formed their line of battle, protected by the heavy woods and elevations on each side of the ride, and from where they could operate their hidden artillery and infantry and keep under fire the unprotected Confederates, while they were being charged on a down grade by cavalry,” recalled a local boy who came out to witness the spectacle of the battle raging in the valley below. “The Confederates were entirely in the open and without any protection whatever, other than the rail fencesâ¦every rail of which showed signs of bullets.”

249

“The enemy began to fire upon us terrifically with his splendid battery, and the increased rattle of musketry, told us that the battle was on,” recalled C.W. Humphreys, a member of Edgar's command.

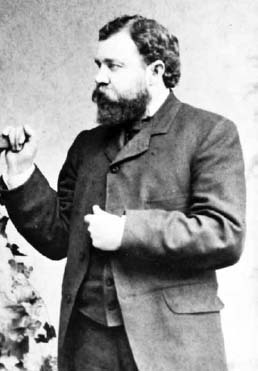

A postwar image of Captain John K. Thompson of the 22

nd

Virginia Infantry.

Terry Lowry

.

Just at this juncture we heard Capt. Thompson in a loud clear voice call out, “Company H, in retreat, march.” Then Capt. Read shouted, “Company B, in retreat, march.” Springing to my feet I saw that the deep hollow in front of us was occupied by the enemy and were quite close to us. They heard these commands to retreat, and a few of them on horseback dashed up to the opposite side of the fence, and were firing at our retreating men with their pistols

.

Humphreys lost his haversack as he hastily retreated. “Good-bye! I may never need you any how,” he thought.

250

Not long after the 45

th

Virginia took position behind its portion of the barricade, Colonel Browne got word from Captain Thompson that he was being pressed in front. Browne sent another company to reinforce Thompson under command of Lieutenant Colonel Edwin H. Harman and ordered him to take command of the troops deployed on the ridge. The men of the 45

th

Virginia could not clearly see the enemy through the thick woods, so they advanced to within fifty yards of Averell's line, “fighting like demons.” However, Harman quickly realized that the two companies could not hold the position.

251

Harman soon afterward reported that a strong force of the enemy was trying to turn the Confederate right. When Browne reported this unwelcome news to Patton, the brigade commander then ordered the entire 45

th

Virginia to move to the hill to check the flanking movement. Browne deployed his regiment with his right resting on the brow of the first hill at a point opposite the tollgate and his left opposite a point on the road about one hundred yards below the smoldering ruins of the Miller house, facing it.

252

The withdrawal of the 45

th

Virginia left George Edgar with only four companies to defend the whole line from the mountain on the right to the field occupied by the 22

nd

Virginia on the left.

253

Patton sent his adjutant, Lieutenant Noyes Rand of the 22

nd

Virginia, with an order for Edgar. Rand had to ride diagonally and toward the enemy's fire in order to deliver the message. Just as his horse jumped a low fence, one of Morton's shells burst under the horse, and the poor beast fell on his belly, pitching Rand about ten feet ahead of his head. The shocked adjutant landed on all fours. “I thought of course he was killed outright,” recalled Rand, “but as the order was very important, and I found I had no bones broken, I never stopped to even look at my horse but proceeded as fast as I could on foot.”

After delivering Patton's order to Colonel Browne, Rand was shocked to find his faithful horse “grazing as if no battle was raging,” so he remounted and returned to Patton's command post. “The horse had evidently struck his feet on the top fence rail at the very moment the shell bursted under him, and so gave the tumble. He was unhurt, but strange to say I found on examination several bullets in my saddleâwhen received God only knows.” Rand also discovered that one bullet had passed clear through his uniform vest from side to side and that another had torn the top of his right shoe and then lodged in his wooden stirrup. The ride had been quite the close call indeed.

254

By the time Browne deployed his troops, Harman had already repulsed Averell's initial attack and then had dealt with a determined assault on the left of the 45

th

Virginia's line. Browne had left Major Alexander M. Davis in charge of the center of his line, and Davis ordered a company forward to support Harman's left wing. This movement drove back Averell's attackers, and Davis advanced his company about one hundred yards beyond and perpendicular to the line of his left wing. Browne also sent two of his companies to reinforce Woodram's position on the ridge.

255