The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (10 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

The 45

th

Virginia saw action at Carnifex Ferry, West Virginia, in 1861. That fall, after his unsuccessful Kanawha Valley Campaign, Wise was relieved of command and sent to Richmond for assignment, and Heth was promoted to general and took command of the brigade. Much of the regiment was reassigned to the 23

rd

Virginia Infantry. With the remnant of the regiment now under command of Lieutenant Colonel William E. Peters, the 45

th

Virginia participated in the Battle of Giles Court House. The regiment was then reorganized. Peters was not elected colonel and left the unit to assume command of a newly formed cavalry regiment, and William H. Browne became colonel of the 45

th

Virginia. The 45

th

Virginia also served in Heth's Kanawha Campaign of 1862, including the Battle of Lewisburg and then with General William W. Loring at Fayetteville and Charleston. The 45

th

Virginia spent most of the winter of 1862â63 guarding the crucial salt mines located around Saltville, Virginia. It was camped at Lewisburg when Averell's command approached and was tasked to defend the town.

175

Colonel William H. Browne was born in Tazewell County, Virginia, on November 9, 1838, and was reared in Jeffersonville (now known as Tazewell). He attended Emory & Henry College for the 1854â55 academic year and then obtained an appointment as a West Point cadet in the class of 1861. Browne resigned a week after the shelling of Fort Sumter in 1861 and never graduated. He was elected captain of Company G of the 45

th

Virginia on May 29, 1861, and was then commissioned colonel after the regiment's reorganization in May 1862.

176

Captain Beirne Chapman's Company of Virginia Light Artillery, otherwise known as Chapman's Battery, also served with Patton's brigade. Chapman's Battery was raised in Monroe County, West Virginia, on April 25, 1862. Chapman had a hodgepodge of ordnance: one twenty-four-pound howitzer, two brass twelve-pound howitzers and two six-pound rifled guns. Chapman's guns participated in the 1862 Kanawha Campaign. The battery consisted of about 125 officers and enlisted men.

177

Captain Chapman, the son of General Augustus A. Chapman, was born on June 23, 1841, in Union, Monroe County, West Virginia. He was a bright student who attended Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, where he studied law. In 1861, while still a student at Washington College, he enlisted as a lieutenant in an artillery company, where he learned to be an efficient cannoneer. He resigned that commission and raised his own company on April 25, 1862.

178

When the battery marched to meet Averell's thrust, Chapman left two guns in Lewisburg and departed with the two three-inch rifles, one twelve-pound howitzer and the twenty-four-pound howitzer. Patton therefore had the same number of guns as Averell.

Patton's veteran brigade numbered about two thousand men. Although elements of other commands from Jones's department would help, Patton's men bore the brunt of the hard fight that was to come in just a few days.

Jones decided to try to corral Averell's column. On August 23, he sent orders to Colonel William H. Browne of the 45

th

Virginia Infantry. “If the enemy attempts to move on Colonel Jackson [at the lovely Gatewood Plantation near Mountain Grove in Pocahontas County, located twelve to fifteen miles from the county seat at Huntersville] by the road from Huntersville to Warm Springsâ¦I think you can get in their rear, and you and Jackson together, perhaps, capture them.” Jones gave Browne an accurate estimate of the size of Averell's force, telling him, “I do not think that Averell had more than 1,200 or 1,300 cavalry.” He told Browne to take his orders from Jackson, even though Browne was senior to Jackson in rank, as Jackson knew the country well from years of operating there. “I trust that you two will manage as to punish the enemy severely before they extricate themselves from the mountainous country into which they have penetrated.”

179

The Gatewood Plantation house.

Pocahontas County Historical Society

.

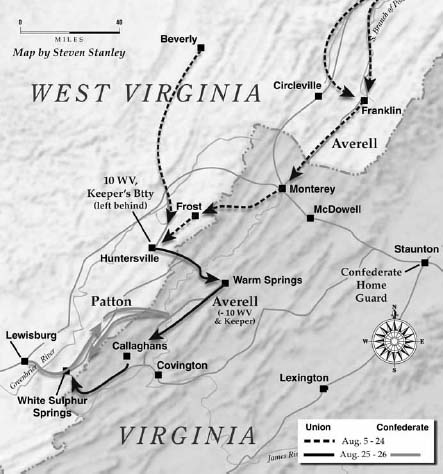

The Confederate pursuit of Averell's raiders.

He also ordered Patton to “move without delayâ¦with your infantry and artillery, up Anthony's Creek, toward the Huntersville and Warm Springs roads, and co-operate with Colonel Jackson. Take with you one company of cavalry, leaving the remainder on the Frankfort and Pocahontas roads, to watch the enemy from that direction.”

180

Jones now had all of the pieces in motion to try to intercept Averell. It remained an open question whether he would be able to do so.

On August 24, Sam Jones reported to the Confederate War Department that Mudwall Jackson and his cavalry had been driven from Huntersville. This came as an unpleasant surprise to Jones, who had ridden the roads with Jackson just a few days earlier and believed that Jackson's horsemen would be able to hold the position long enough to enable him to send a supporting force in time to help. “I have ordered such movements of troops from Lewisburg as I think will check them and frustrate their plans,” he said. “I am apprehensive that the cavalry may be on a raid to the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. I have no troops on that road.” He then asked for reinforcements to garrison the railroad, including the brigades of Brigadier General Albert G.Jenkins (then commanded by the brigade's senior colonel, Milton J. Ferguson of the 16

th

Virginia Cavalry, as Jenkins had received a serious wound at Gettysburg) and Colonel Gabriel Wharton.

181

Although Robert E. Lee approved the transfer of these two brigades, Ferguson and Wharton were too far away and could not get there in time, meaning that Patton would have to make due with the troops he had at his disposal and could not count on reinforcements.

Jones also called out the Home Guard that day, sending them scrambling to defend the important railroad bridge over the New River. “Have your guns and ammunition issued to your company immediately,” he instructed the commander of the Home Guard detachment at Wytheville. “The enemy's cavalry, 1,200 strong, are reported advancing on New River Bridge. Hold your command in readiness to move at a moment's warning.”

182

As many as one thousand home guardsmen reported to defend the New River Bridge, and another two thousand men came out from Lynchburg in the direction of Lewisburg in an effort to bolster Patton's force.

183

Jones also set Patton's brigade in motion from Lewisburg, with the task of stopping Averell's advance. Jones joined Patton and his foot soldiers on the Anthony's Creek road on August 25. That morning, Jones received a note from Mudwall Jackson dated 9:00 a.m. the previous morning, indicating that Jackson had driven Averell's skirmishers back to his old camp near Huntersville. “The tenor of the dispatch induced me to believe that he could not only check the opposing force at Gatewood's but could move up and join [Patton's Brigade] at the intersection of the Anthony's Creek road from Huntersville to Warm Springs,” reported Jones. “I dispatched him, informing him of the movement of that brigade, and directed him, if possible, to join it at the junction of the two roads above mentioned.” However, Jones concluded that Jackson had never received the message and that the courier was captured.

184

Uncertain of Averell's objective, Brigadier General John D. Imboden, who commanded the Valley District, called out the Home Guard in the Staunton area. Local citizens flocked to the armory in Staunton, where they were organized into an artillery company, two infantry companies and a company of Home Guard cavalry. “The whole town presented an attitude of defiance,” reported a correspondent. “Men of over 60, with boys of 12 and 15, took their places in the ranks and shouldered shot-gun or rifle with alacrity. By mid-day, it was ascertained thatâ¦the danger was not so imminent. The people were dismissed with orders, however, to gather in the same organizations at a moment's call. Many seem to feel disappointment, mingled with relief, so keen had they become to meet the invading foe. This they will do, and I feel sure no small number of the enemy will find themselves able to reach our town. I learn that the country is also bristling in arms.”

185

Later that day, Jones learned of Jackson's rout by Averell. Still believing that the Federals' objective was Staunton, Jones ordered Patton to turn off from the Anthony's Creek road and take a shorter route to Warm Springs in order to meet the threat, meaning that Jones took Averell's bait and fell for the ruse. At the same time, Jones ordered Colonel James M. Corns and his five companies of the 8

th

Virginia Cavalry to march to White Sulphur Springs to intercept Averell.

186

He also ordered the local citizenry to remove their valuables, lest the Yankees plunder them.

187

The local citizenry fled from Warm Springs, “where great consternation had prevailed.”

188

“My comrades who were on that march will recall the haste in which this order was executed, the silence enjoined on officers and men, who in a high state of expectancy, rivaled âJackson's Foot Cavalry' in the rapidity with which they covered the ground,” remembered Lieutenant Colonel George M. Edgar of the 26

th

Battalion of Virginia Infantry. In the evening, they bivouacked “on a brushy slopeâ¦which after they encountered formidable dens of snakes, [and] eating a hasty meal, were soon in profound slumber.” The men of Patton's command still had no idea what emergency faced them.

189

Conflicting reports swirled. A telegraphic dispatch from Staunton claimed “that the Yankees are falling back, which is very probable, as [the Northwestern Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General John D.] Imboden is on their track. Their object seems to be the destruction of the [Virginia] Central railroad.”

190

This sort of speculation only further muddied the waters as the Confederate authorities grappled with trying to ascertain the true objective of the invasion.

About ten o'clock that night, Jones learned the truth: that Averell was advancing from Warm Springs toward Callaghanâin other words, that the Union horsemen were going the opposite way. “I immediately ordered Colonel Patton to return on the Anthony's Creek Road in the hope of intercepting the enemy on the road from the Warm to the White Sulphur Springs.” Word reached Patton's bivouac about two o'clock that morning. By a forced night march, the Virginians marched to the mouth of Anthony's Creek, crossed the Greenbrier River Bridge and came out on the road to White Sulphur Springs. They then turned onto the Midland Trail, with Edgar's troops leading the way.

191

After nearly twenty-four straight hours on the road, the Virginia infantrymen were within a mile and a half of the crucial road intersection. The advance guard reached the intersection just in time to meet the advance of Averell's column on the morning of August 26.

192