The Battle of Hastings (8 page)

Read The Battle of Hastings Online

Authors: Jim Bradbury

To the west there was trouble between the Bretons and Scandinavian settlers along the Loire, and the Normans intervened for their own profit. By 933 William had gained western Normandy as far as the Couesnon, which it seems he had recovered from the Bretons, adding the Cotentin and the Avranchin, though comital power in these areas remained weak through the next century.

17

Normandy as we recognise it had been created, or perhaps recreated, since it responded closely to the old ecclesiastical province of Rouen and the even more ancient boundaries of the Roman province of

Lugdunensis Secunda

; it also had a rough correspondence to the Frankish region of Neustria, which it was still sometimes called. William Longsword established a family connection with Fécamp, where a palace was constructed.

William Longsword was christian and encouraged Christianity. He married a christian noblewoman, Liégarde, daughter of the count of Vermandois, though his successor was born to a Breton mistress.

18

But Christianity’s revival in Normandy proved slow and uncertain. Five successive bishops appointed to Coutances were unable to reside in their see. Bishops appointed outside Rouen also found themselves unable to live in their own sees.

However, William I was known as a friend of monastic restoration, and was especially associated with the great house of Jumièges. In 942, the year of his death, William welcomed King Louis IV of France (936–54) to Rouen, which suggests that he recognised the king’s authority over Normandy. Neither the emphasis on Christianity, nor the friendship with the West Frankish monarchy, seems to have been favoured by William’s subjects, and may have been the cause of his assassination in 942. His death, though treated by some as martyrdom, led to a pagan revival in Normandy, and a period of disorder.

William Longsword’s son succeeded as Richard I (942–96). He grew into ‘a tall man, handsome and strongly built, with a long beard and grey hair’. But in 942 he was only ten years old, and as usual a minority meant disorder and difficulty.

19

Scandinavian raids were still occurring, and were a cause of disturbances within Normandy. The king of France and the duke of the Franks established themselves in Norman territory, and won a victory against the Viking leader Sihtric. They looked for the overthrow of the Viking county rather than the defence of Richard. But in 945 Louis IV was himself defeated by Harold, a Viking leader probably based in Bayeux.

20

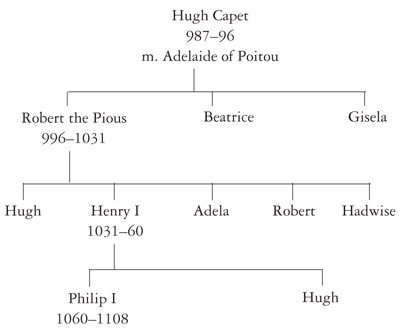

Capetian Kings of France: Hugh Capet to Philip I.

Gradually, over the years, Richard I emerged as a man of strength and determination. He took as his wife, though perhaps not by a Christian ceremony, a woman of Danish descent called Gunnor, from a family settled in the pays de Caux. By her he had several children, including his eventual successor. Most members of the Norman nobility of the Conqueror’s time claimed some sort of relationship either with Richard I or with Gunnor, which brought a coherence to the ruling group that in turn added strength to their combined efforts at expansion.

21

Given the circumstances of the minority, it is hardly surprising that Richard I continued to keep links with Scandinavia, but he also made an agreement with the new king, Lothar, at Gisors in 965. For a long period after this the ruler of Normandy kept on good terms with the king of the West Franks, of importance to them both.

But Richard I did not continue his support for the old Carolingian family. He had already been closely associated with the duke of the Franks, and took as his ‘official’ wife, Emma, daughter of Hugh the Great, duke of the Franks (d. 956). The Normans were among the firmest supporters of this family. In 968 Richard I recognised Hugh the Great’s son, Hugh Capet, as his overlord, and when Hugh became the first Capetian king of France (987–96) the Normans were among his earliest adherents. Richard also sought to restore Christianity, and from this time on paganism in Normandy waned. One of his most enduring acts was to aid the revival of the monastery at Mont-St-Michel. Richard I’s reign also saw the beginnings of an important monastic revival in Normandy.

Richard II (996–1026) succeeded his father in a year marked by a peasant revolt in Normandy. The peasants called assemblies, and made ‘laws of their own’, but the movement was brutally suppressed by the nobility.

22

When the count of Ivry was approached by rebels to put their case, he cut off their hands and feet. But the new reign was a period of significant economic progress for Normandy. Despite being ‘highly skilled in warfare’, Richard II kept out of the conflicts which raged around him in north-west Europe, though he did push Norman interests beyond his own boundaries. He had ‘decidedly pacific tendencies’, and brought a period of significant stability to the duchy.

23

Richard II married the sister of the count of Rennes, the ‘fair of form’ Judith.

24

He also had contacts with the Scandinavian world: Vikings could still be welcomed at Rouen in 1014, and a Norse poet was received at court in 1025. To Franks outside Normandy the rulers still seemed Vikings, and Richer of Reims continually referred to Richard as ‘duke of the pirates’. The name given to the territory itself, ‘Normandy’, came from the same attitude to its inhabitants, meaning the land of the northmen or Vikings.

But Scandinavian influence was decreasing in Normandy. Place-name studies suggest that the original Scandinavian settlement did not extend evenly throughout Normandy. The names cluster along the coast and the rivers. It is clear in any case that the settlers began to integrate with the existing population through intermarriage. Some Scandinavian attitudes and customs continued but, as is so often the case, the surviving population from the old world recovered its strength, if only in influencing language and a way of life. By the tenth century French was taking over as the main language in Normandy, if it had ever been overtaken. According to David Douglas, by the eleventh century Normandy was ‘French in its speech, in its culture, and in its political ideas’.

25

The administrative system which developed in Normandy was largely Frankish, and similar to that in surrounding counties. We have a nice picture of Richard II at Rouen, in ‘the city tower, engaged in public affairs’. We are told that those in attendance feared to break in upon him unless summoned by his chamberlains or doorkeepers: ‘but if you wish to see him, you can watch him at the usual time, just after dinner, at the upper window of the tower, where he is in the habit of looking down over the city walls, the fields and the river’.

26

Richard II continued the family’s reputation for defending the Church, and was responsible for inviting to Normandy the reformer William of Volpiano. By this time the episcopal organisation of Normandy had developed, and the bishops were able to function normally within their sees. Under Richard II a new social structure of Normandy emerged. It is clear now that this was not the emergence of new families, but of old families in a new guise: as castellans, with stress on primogeniture and lineage. The families were not new, but their way of looking at themselves and their ancestry was.

There is, for example, no mention of the Montgomerys (one member of whom considered himself ‘a Norman of the Northmen’) before a charter dated to 1027 at the earliest, after Richard’s death. Montgomery itself was not fortified until after 1030. The use of toponyms to define an individual and his family did not become common until about 1040.

27

It was about this time that the residence at Le Plessis-Grimoult was turned into a castle. During the period of political instability old families began to see themselves as lineages, to build castles, to latch on to offices at the ducal court, to become vicomtes in ducal administration of the duchy, indeed to threaten ducal power itself.

28

Richard II married twice, to the Breton Judith, whose sons, Richard and Robert, succeeded him, and to the Norman Papia, by whom he had two further sons, William of Arques and Mauger, the later Archbishop of Rouen. Richard II used members of his family to rule over divisions of his territory on his behalf: at Mortain, Ivry, Eu, Évreux and Exmes. It was the acknowledgement of the rights of this second family which caused many of the problems of the subsequent period.

With local magnates called counts came the transfer of the ruler’s title from count to duke, marking his superiority. Those appointed to rule over the new Norman counties, mostly in sensitive areas on or near the frontier, were members of the ducal family. Ducal government also developed, and we begin to hear of vicomtes, who were not deputies for the counts, but were all direct representatives of the count of Rouen himself, that is of the duke. During the period 1020 to 1035 some twenty vicomtes have been identified, and they represent a growing structure for comital government throughout Normandy.

N

ORMANDY IN

T

ROUBLE

After the death of Richard II in 1026, Normandy underwent a long period of difficulty. The next duke, Richard III, survived only a year, until 1027. There was rumour that he had been poisoned, possibly by his successor.

29

Robert I (1027–35) was the only member of the family of Rolf who proved something of a failure, despite being known as Robert the Magnificent or sometimes the Liberal, and reputed to be ‘mild and kind to his supporters’, with an ‘honest face and handsome appearance’, and of a ‘fine physique’.

30

Others, it must be said, called him Robert the Devil.

External relations deteriorated, and Normandy faced a period of severe internal disorder. Yet the duchy retained vestiges of its earlier position. When King Henry I of France (1031–60) found himself in desperate trouble in the year of his accession, it was to Normandy that he fled for refuge. Surviving gratitude for this help accounts for his aid to the young William the Conqueror during the latter’s minority, the years of his greatest vulnerability.

Robert’s decision to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land is something of a puzzle. Perhaps he was overcome with piety, though his life to that date shows little sign of it. Perhaps he was overcome by remorse, for which he no doubt had good cause. However, for his duchy it was a perilous moment to depart on such a distant adventure, from which, as might have been feared, he was never to return, dying unexpectedly at Nicaea during his return journey.

One of Robert I’s sins was a liaison with Herlève, variously said to be the daughter of a tanner or perhaps an undertaker of Falaise called Fulbert.

31

In any case the duke, as dukes will, had his way with her, made her pregnant without any thoughts of marriage, and thus fathered William the Bastard, perhaps Robert’s chief contribution to his duchy.

When you look down nowadays from the walls of the great stone castle at Falaise (not in that state when Duke Robert lived), you are told that you are standing (presumably approximately) where Robert was when he espied the fair Herlève beside the pond below, outside the castle wall. Another story is that he had ‘accidentally beheld her beauty as she was dancing’. The twelfth-century writer described William’s birth, on rushes laid out on the floor, and said that Herlève had a dream about her new son: she saw her intestines spread out over Normandy and England which forecast William’s ‘future glory’!

32

William the Conqueror (William II, duke of Normandy, 1035–87) thus came to rule the duchy in unpromising circumstances. His father had died when William was aged about nine, possibly even younger. The duchy had passed through decades of instability, which had included a peasants’ revolt and divisions among the aristocracy, while ‘many Normans built earthworks in many places, and erected fortified strongholds for their own purposes’.

33

Added to that, William was not the legitimate son of the old duke. Bastardy was not the stain it was about to become in terms of moral attitude or right to inherit, but it was, nevertheless, a drawback, as one can see from the very fact that he was called ‘the Bastard’, and from the way the citizens of Alençon and others later would taunt him with his bastardy. William’s reaction to this insult at Alençon shows how much it smarted: he ordered the hands and feet of thirty-two mockers to be cut off. A chronicler considered that ‘as a bastard he was despised by the native nobility’.

34

The taint of bastardy added to the dissatisfaction of the nobles at having a minor succeed to the duchy.

William’s own relatives were among those who stirred up trouble during his minority, suggesting the unwise nature of Richard II’s acknowledgement of families by two wives. The period was marked by a series of internal rebellions and external threats. At times, William’s security, and even his life, was at risk. At Valognes, he was once roused from sleep to be warned that conspirators were about to kill him; William got away half-dressed on a horse. He was protected by a few loyal retainers and given some support from the Church and by the king of France, but he often escaped by the skin of his teeth. Among those around him who were killed were his guardian Gilbert de Brionne, his tutor Turold, and his steward Osbern.

35