The Battle of Hastings (4 page)

Read The Battle of Hastings Online

Authors: Jim Bradbury

In the event, Harthacnut, like all of his half-brothers except Harold, was out of the country. The two in Normandy, the sons of Aethelred and Emma, were given some hope from a recent breach between Cnut and the new Norman duke Robert I (1027–35). But Robert went to the Holy Land and then died in 1035, so that Alfred and Edward were in no position to intervene in England. Meanwhile, Sweyn, the son of Cnut and Aelfgifu, like Harthacnut, was occupied by Scandinavian troubles at the time.

Harthacnut had his father’s blessing and the aid of his closest followers, his mother’s encouragement, and the support of the two men who mattered most at the time: the Archbishop of Canterbury and Earl Godwin. Sweyn’s brother, Harold Harefoot, did have northern support, from the earls of Mercia and Northumbria, perhaps chiefly in order to oppose southern interests; but they would not have had the capacity to displace Harthacnut had he been present.

However, Harthacnut’s continued failure to come to England decided the issue. His support did not entirely die out, but it reduced. Most of those concerned realised that there must be a king in position, and Harold Harefoot gradually gained supporters from the south. Emma seems to have toyed with ambitions for her older sons in Normandy and probably wrote to get them to come to England, no doubt in order to seek the succession.

26

Edward did not come to England, but his younger brother Alfred did, probably buoyed with false hopes from his mother’s encouragement. Unfortunately for him, by the time he arrived Earl Godwin had decided that his best bet was to accept Harold Harefoot, who, as Harold I, was established in power. What happened next is not certain, and Godwin’s supporters claimed him innocent. The likelihood is that he cooperated with Harold I in the capture and murder of Alfred. Godwin took him to Guildford, where, after a day of feasting, Harold’s men attacked at night and captured the young man. He was blinded and taken to Ely where he shortly died.

After all this effort to gain the throne, Harold I (Harefoot, 1035–40) had a brief and miserable reign. Emma had acted deviously over the succession, first favouring Harthacnut and taking control of the treasure at Winchester, then turning to her sons in Normandy. She even seems to be responsible for trying to undermine Harold by disinformation, spreading the tale that he was really the son of a servant, some said of a cobbler.

27

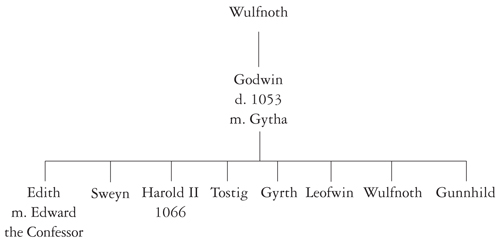

Godwin’s family.

When Harold Harefoot’s success was certain, Emma chose to remove herself to the safety of Flanders. But like other political women of the medieval period, she had tasted too much power to go away quietly. In Bruges, after the death of Harold Harefoot, she met both her surviving son by Aethelred, Edward (the Confessor), in 1038, and then her son by Cnut, Harthacnut. She seems to have achieved some alliance between them. The latter had agreed a settlement with Magnus of Norway in 1038, and belatedly in 1039 began to take action over his rights in England. He had brought a fleet of ten ships to Flanders, but in the event did not need any greater force to invade England because of Harold I’s sudden death in March 1040.

Now Harthacnut (1040–2) was able to add England to Denmark and revive some semblance of his father’s empire. He had raised a fleet of sixty ships, envisaging the need for invasion, and sailed with it to Sandwich, accompanied by the ever ambitious Emma. She gave assistance in his attempt to resolve the Norman threat. Through her Harthacnut had come to terms with his half-brother Edward, who was also invited to return to England in 1041. Edward was to have an honoured place at court, and may even have been treated as Harthacnut’s co-king or heir.

28

Harthacnut ruled harshly but effectively. In Worcester in 1041 there was opposition to heavy taxation. Two collectors were forced to take refuge in a room at the top of a church tower, but even that refuge failed them and they were murdered. Harthacnut sent a force which ravaged the shire, killing all males who came before it in a four-day orgy of revenge.

The long period of uncertainties with many twists of fortune and several sudden deaths reached a new resolution with Harthacnut himself succumbing to the grim reaper at Lambeth in June 1042, when over-indulging at a wedding feast: ‘he was standing at his drink and he suddenly fell to the ground with fearful convulsions, and those who were near caught him, and he spoke no word afterwards’.

29

Notes

1

. William of Poitiers,

Histoire de Guillaume le Conquérant

, ed. R. Foreville, CHF, Paris, 1952, p. 206.

2

. D.C. Douglas,

William the Conqueror

, London, 1964, p. 181 and n. 1; R.A. Brown,

The Normans and the Norman Conquest

, 2nd edn, Woodbridge, 1985, p. 122; Orderic Vitalis,

The Ecclesiastical History

, ed. M. Chibnall, 6 vols, Oxford, 1968–80, ii, p. 134 and n. 2; C. Morton and H. Muntz (eds),

Carmen de Hastingae Proelio

, Oxford, 1972, p. 10, ll. 125–6.

3

. D. Whitelock, D.C. Douglas and S.I. Tucker (eds),

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, London, 1961, 1012, pp. 91–2; G.P. Cubbin (ed.),

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, vi, Cambridge, 1996, p. 57.

4

. Asser, ‘Life of King Alfred’ in S. Keynes and M. Lapidge (eds),

Alfred the Great

, Harmondsworth, 1983, p. 98; compare John of Worcester,

Chronicle

, eds R.R. Darlington and P. McGurk, ii, Oxford, 1995 (only this vol published to date), p. 324.

5

. John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, pp. 354, 378.

6

. John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, p. 412.

7

. E. John, chaps. 7–9, pp. 160–239 in James Campbell (ed.),

The Anglo-Saxons

, London, 1982, pp. 160, 172.

8

. John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, p. 428, Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 79.

9

. John in Campbell (ed.),

Anglo-Saxons

, p. 192.

10

. S. Keynes,

The Diplomas of King Aethelred ‘the Unready’

, Cambridge, 1980, p. 158.

11

. John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, pp. 430, 436; John in Campbell (ed.),

Anglo-Saxons

, p. 193; F. Barlow,

Edward the Confessor

, London, 1970, p. 3; Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 986, 1005, 1014, pp. 81, 87, 93.

12

. Barlow,

Edward

, p. 4.

13

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 991, p. 82; John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, p. 452.

14

. Barlow,

Edward

, p. 11; John in Campbell (ed.),

Anglo-Saxons

, p. 198.

15

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 999, p. 85.

16

. M.K. Lawson,

Cnut

, Harlow, 1993, p. 43.

17

. Barlow,

Edward

, p. 15; Lawson,

Cnut

, p. 17.

18

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 1002, p. 86; Keynes,

Diplomas

, pp. 203–5; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 51.

19

. John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, pp. 456, 470: ‘

perfidus dux

’.

20

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 92; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 58.

21

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 1014, p. 93; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 59.

22

. W.E. Kapelle,

The Norman Conquest of the North

, London, 1979, e.g. p. 26.

23

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 1016, p. 95.

24

. Lawson,

Cnut

, p. 38.

25

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 1017, p. 97.

26

. John in Campbell,

Anglo-Saxons

, p. 216.

27

. Barlow,

Edward

, p. 44; John of Worcester, eds Darlington and McGurk, p. 520.

28

. Barlow,

Edward

, p. 48; Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, C and D, 1041, p. 106.

29

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, 1042, p. 106; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 66

T

HE

R

EIGN OF

E

DWARD THE

C

ONFESSOR

E

dward the Confessor (1042–66), who had probably been present at his predecessor’s death, was to have a lengthy and relatively secure reign. The drawing of him in the manuscript of the

Encomium Emmae

, written by a cleric of St-Omer for Queen Emma, is the best likeness we have. In it he appears with trimmed hair in a fringe and a short, wavy beard with perhaps the hint of a moustache. While in the

Vita

, written for his wife, Edith, he is described as ‘a very proper figure of a man – of outstanding height, and distinguished by his milky white hair and beard, full face and rosy cheeks, thin white hands and long translucent fingers … Pleasant, but always dignified, he walked with eyes downcast, most graciously affable to one and all’.

1

He could also be thought ‘of passionate temper and a man of prompt and vigorous action’, but Edward was no soldier. The medieval writer who said ‘he defended his kingdom more by diplomacy than by war’ had it right; but failure to act as a commander of men was a grave disadvantage in this period.

2

We should be under no illusion but that the Scandinavian conquest and the frequent switches of dynasty during the first half of the eleventh century had greatly weakened the kingdom. There were no other surviving sons of either Aethelred II or Cnut, but there were too many with claims and interests in England for its good. For example, Sweyn Estrithsson was the grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard; he was to become king of Denmark, and was not keen to see the old Saxon dynasty replacing that of his own line in England. Meanwhile, Magnus of Norway still saw possibilities for his own expansion. Later he was succeeded by the famed adventurer Harold Hardrada, who also dreamed of bringing Scandinavian rule back to England. Nor was Edward’s reign free from Viking raids of the old kind.

The northern earls, Leofric and Siward, accepted Edward, but cannot have been enthusiastic about his succession. The north had never been firmly under southern control, and would continue to offer threats to the peace of England under Edward. Nevertheless, given the difficult period before Edward’s accession and the long-term weaknesses displayed by the troubles, the Confessor’s reign was better than one might have expected. The view of Edward as ‘a holy simpleton’ is not easy to maintain.

3

At least some historians now are prepared to be more respectful to the Confessor.

He could expect renewed attacks from Scandinavia, hopes of reward from Normandy, which might be difficult to satisfy, and opposition from at least some of the English magnates. His new realm was divided between English and Scandinavian populations, and into politically powerful earldoms. His most powerful earl, Godwin of Wessex, had been implicated in the murder of his own brother, Alfred.

At the same time, Edward possessed an advantage which most had lacked during the century: he was indisputably king and, unlike his immediate predecessors, he came from the old house of Wessex. He was also wealthy. His own possessions were valued at about £5,000, with an additional £900 coming through his wife. This made him wealthier than any of his magnates, including Godwin, though royal landed wealth was unevenly distributed, and in some areas of the realm the king held very little.

4

Edward’s position was helped further by the death of Magnus, king of Norway and Denmark, in 1047. The Confessor’s Norman mother and Norman upbringing – he had received an education at the ducal court and it is said was trained as a knight – gave him the probability of a good relationship with that emerging power.

5

His sister, Godgifu, had married from the Norman court into the French nobility, and this gave Edward a number of noble relatives on the continent. But in any case, in the early years of the reign England could expect neither aid nor opposition from Normandy, which was undergoing much internal turmoil during the minority of William the Bastard.