The Battle of Hastings (2 page)

Read The Battle of Hastings Online

Authors: Jim Bradbury

The English kings had been more successful by the eleventh century than their Capetian counterparts in establishing authority over the great magnates in the provinces. In the case of England, this meant over the former kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia. Historically, since the royal dynasty had come from the former kingdom of Wessex, which had in earlier centuries established authority over much of the south, the kings could usually rely on holding that area safely, but the hold over the northern areas was less certain.

The Wessex kings had faced invasion from without as well as opposition from within. The success of Alfred the Great had been only partial, and Scandinavian settlement often provided a fifth column of support for any Scandinavian-based invader. Such invasions brought periods of severe instability. Ironically, although in many ways England was better unified and economically stronger by the eleventh century than it had been, it was also less politically stable.

These two threads, of economic and political advance on the one hand, and invasion and instability on the other, are our main themes in this chapter. The political instability encouraged hopes of success by invaders, while the economic success provided wealth, which gave a motive for making the attempt. The history of England from the ninth century onwards is marked by periods of crisis.

The most consistent cause for this was the threat from Scandinavia. The earliest Viking raids had been mainly by the Norse, but through the ninth century the chief danger came from the Danes. The Scandinavian threat was at the same time the spur towards unity and the threat of destruction to the kingdom of England. From the middle of the ninth century the scale of the raids increased, so that large fleets of several hundred ships came, carrying invaders rather than raiders.

In the ten years from 865, East Anglia, Northumbria and half of Mercia had been overrun. The Vikings attacked and conquered the great northern and midland kingdoms – Northumbria, with its proud past achievements, and Mercia, which under Offa had dominated English affairs through much of the ninth century. As earldoms, these regions would have a continued importance, but after the Danish conquest they would never again be entirely independent and autonomous powers.

The Scandinavian invasion was also a threat to Christianity, by now well established in England. When the Viking attacks began the raiders were pagan and the wealth of the churches and monasteries became a lucrative target. Even by 1012 the Vikings could seize and kill Aelfheah, the Archbishop of Canterbury, when he refused to be ransomed: ‘they pelted him with bones, and with ox heads, and one of them struck him on the head with the back of an axe so that he sank down with the blow and his holy blood fell on the ground’.

3

It does not suggest much respect for organised Christianity. Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut were committed Christians, but many of their followers were still pagan. One notes that in the 1050s an Irish Viking leader made a gift of a 10-foot-high gold cross to Trondheim Church, but it was made from the proceeds looted during raids into Wales.

The Viking conquest pushed the separate kingdoms and regions of the English into a greater degree of mutual alliance. History, race and religion gave a sense of common alienation from these attackers: ‘all the Angles and Saxons – those who had formerly been scattered everywhere and were not in captivity to the vikings – turned willingly to King Alfred, and submitted themselves to his lordship’.

4

So the Viking threat played a major role in bringing the unified kingdom of England into being.

The reign of Alfred the Great (871–99) was of fundamental importance in the unification process. After a century of Viking raids, the English kingdoms crumbled before the powerful Scandinavian thrust of the later ninth century. Alfred could not have expected his rise to kingship: he was the last of four sons of Aethelwulf to come to the throne. Though severely pressed, Alfred saved Wessex in a series of battles which culminated in the victory at Edington and the peace treaty at Wedmore.

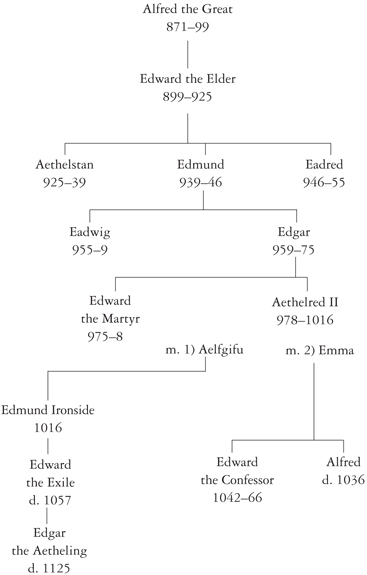

Wessex dynasty Kings of England

Wessex was the only surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, and the nucleus for a national monarchy. The taking over of London by Alfred in 886 was a significant moment in the history of the nation. Alfred was also instrumental in the designing and implementing of a scheme of national defence through the system of urban strongholds known as burhs. Each burh had strong defensive walls and was maintained by a nationally organised arrangement for maintenance and garrisoning. He also reorganised the armed forces, establishing a rota system which meant that a permanent army was always in the field, and building a fleet of newly designed ships for naval defence.

Alfred’s successors as kings of Wessex and England, his son Edward the Elder (899–924) and his grandson Aethelstan (924–39), increased the authority of the crown over the northern and midland areas. Already by the early tenth century, all England south of the Humber was in Edward the Elder’s power. Even the Danes in Cambridge ‘chose him as their lord and protector’.

5

He won a significant victory against the Vikings of Northumbria in 910 at Tettenhall. Aethelstan married the daughter of Sihtric, the Norse king of York, and on his father-in-law’s death took over that city. The hold on the north was not secure, and would yet be lost to Scandinavian rule, but Aethelstan could truly see himself as king of England.

Edward the Elder and Aethelstan also extended the burghal system as they advanced their power, and improved the administrative support of the monarchy, making themselves stronger and wealthier in the process. Over thirty burhs were developed, containing a sizeable proportion of the population. It is said that no one was more than 20 miles away from the protection of a burh. They also gave a safe focus for the increasing merchant communities engaging in continental as well as internal trade. By 918 Edward was in control of all England south of the Humber, while Aethelstan could call himself ‘the king of all Britain’, which his victory at Brunanburgh in 937 to some extent confirmed.

Edmund (939–46) succeeded his brother Aethelstan, but his assassination by one of his subjects, in the church at Pucklechurch, Gloucestershire, in 946, brought a new period of crisis. For a time the Scandinavians re-established their power at York, and a threatening alliance was established with Viking settlers in Ireland. Recovery began with the efforts of the provincial rulers, the ealdormen, rather than from any exertions by the monarchy, through such men as Aelfhere in Mercia, Aethelwold in East Anglia and Byrhtnoth in Essex. Thus Mercia was recovered in 942, and Northumbria in 944. The expulsion of Eric Bloodaxe from York in 954 finally brought the north under southern influence again.

The monarchy recovered through the efforts of Edgar (959–75). He was ‘a man discerning, gentle, humble, kindly, generous, compassionate, strong in arms, warlike, royally defending the rights of his kingdom’; to his enemies ‘a fierce and angry lion’.

6

A clearer picture emerges of the government of the land through shires and courts. It was the time of the great church leader Dunstan, who became Archbishop of Canterbury and oversaw important monastic reform and revival. On a famous occasion seven (possibly eight) ‘kings’ from various parts of the British Isles came to Edgar at Chester and, to symbolise his lordship over them, rowed him in a boat on the River Dee. It was Edgar who made an agreement with the king of Scots, which for the first time established an agreed boundary between their respective kingdoms.

Edgar also reformed the coinage, and by his time there is good evidence for such regular features of government as a writing office, the use of sealed writs, a council known as the witenagemot, and the writing down of laws. Under Aethelstan and Edgar, the ealdormen gained a broader power, often over former kingdoms – Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria. Their power has been seen as vice-regal. Beneath this was developing the organisation of shires, themselves subdivided into hundreds, probably for military reasons in the first place, but certainly also for the convenience of local administration under the monarchy. Edgar’s reign has been called ‘the high point in the history of the Anglo-Saxon state’.

7

Edgar was only thirty-two when he died in 975. His son Edward (the Martyr, 975–8) succeeded him. Although he quickly made himself an unpopular king, his murder at Corfe in 978 was widely condemned and blamed upon his brother Aethelred, who thereby gained the throne. Edward was hurried to his grave, according to the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

: ‘without any royal honours … and no worse deed than this for the English people was committed since first they came to Britain’.

8

Aethelred was very young, and is unlikely to have had any real part in the killing, but it is possible that his mother (Edward’s stepmother) had, and men from Aethelred’s household were implicated. The irritable and unlikeable Edward ironically has gone down in history as Edward the Martyr, though it is unlikely that he sought death or that piety was in any way involved. It was claimed that ‘strife threw the kingdom into turmoil, moved shire against shire, family against family, prince against prince, ealdorman against ealdorman, drove bishop against the people and the folk against the pastors set over them’.

9

Natural phenomena, like the comet, were always noted and taken as presages of the future. In the year of Aethelred’s ascension the Anglo-Saxon chronicler reported that: ‘a bloody cloud was often seen in the likeness of fire, and especially it was revealed at midnight, and it was formed in various shafts of light’. It was an inauspicious beginning to the unfortunate rule of Aethelred II (978–1016), though he was ‘elegant in his manners, handsome in visage, glorious in appearance’, it was to be ‘a reign of almost unremitting disaster’. Work on his charters has shown something of how his government worked, but has done little to retrieve his reputation in general.

10

One charter read: ‘since in our days we suffer the fires of war and the plundering of our riches, and from the cruel depredations of our enemies … we live in perilous times’.

In 986 there was a ‘great murrain’; in 1005 a ‘great famine throughout England’, the worst in living memory; in 1014 there was flooding from the sea which rose ‘higher than it had ever done before’, submerging whole villages. Of 987 it was said there were two diseases ‘unknown to the English people in earlier times’, a fever in men and a plague in livestock, called ‘scitte’ in English, and ‘

fluxus

’ of the bowels in Latin, so that many men and almost all the beasts died. Ravaging and natural disasters seemed to match each other in their destruction.

11

We know the king, through mistranslation, as Aethelred the Unready. The name Aethelred means noble or good counsel, and he was punningly nicknamed ‘unraed’, which means not unready but bad, evil or non-existent counsel, making him ‘Good Counsel the Badly Counselled’; or perhaps ‘Good Counsel who gives bad advice’.

12

The death of Edward immediately set that king’s close followers against Aethelred. Aethelred’s reign in many ways is representative of the whole dilemma for English kings in the pre-Conquest period: whether to concentrate most on the fight to maintain stability at home, or to focus on defence.

It was in this period that the Viking threat emerged once more, and on a greater scale than ever previously. If one thinks how close England had come to submission when defended by the great Alfred, it is less surprising that a threat greater than he faced should be too much for the less impressive Aethelred II. The major difference was that leading Scandinavian figures, including ruling monarchs, now became involved in the attacks on England. Conquest rather than raiding became a clear objective.

The new wave of threats opened with the raid of Olaf Tryggvason in 991. Aethelred himself did not take part in the main attempt to deal with this attack, when an army met the Danes at Maldon. A famous poem commemorates the event. The English leader, Ealdorman Byrhtnoth, seems overconfidently to have allowed the Vikings to cross from Northey Island to the mainland, no doubt believing he would be able to defeat them in battle. He had miscalculated: the battle was lost and he was killed. Viking attacks increased in the eleventh century with the invasion of Sweyn Forkbeard, king of Denmark (983–1014), soon aided by his son Cnut. During the eleventh century there were at least five attempts at invasion, three of which succeeded.

Aethelred pursued a policy of attempted appeasement, paying tributes to the attackers. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

records in 991: ‘it was determined that tribute should first be paid to the Danish men because of the great terror they were causing along the coast’, and it was even recognised as ‘appeasement’.

13

Tribute was paid in that year of £10,000, and again, for example, in 994, 1002, 1007 and 1012.

Promises were made not to attack again in return for large sums of money. The promises were sometimes kept and sometimes ignored. In any case the hope of obtaining such easy reward for simply going away was not likely to have a deterrent effect. This was expressed by an Englishman as ‘in return for gold we are ready to make a truce’. Over half a century some £250,000 was paid in tribute.

14

One has the vision of Viking leaders scrambling over each other in haste to get at the cash from wealthy but weak England. One tribute paid in order to buy time so that on the next occasion a solid fight might be made would have been one thing; but tribute followed by tribute followed by tribute, in what became virtually an annual ritual, presented little hope of resolving or even lessening the problem. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

thought that these efforts caused ‘the oppression of the people, the waste of money, and the encouragement of the enemy’.

15