The Articulate Mammal (21 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

Chomsky assumed that children would somehow ‘know’ about deep structures, surface structures and transformations. They would realize that they had to reconstruct for themselves deep structures which were

never

visible on the surface.

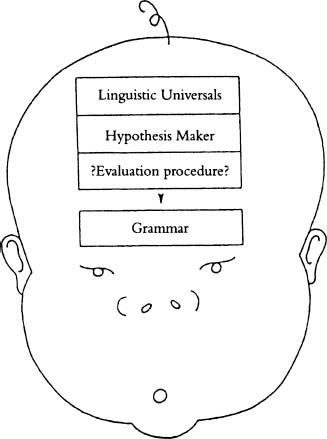

To summarize so far, we have been outlining Chomsky’s ‘classic’ (1965) viewpoint. He assumed that children were endowed with an innate hypothesismaking device, which enabled them to make increasingly complex theories about the rules which would account for the language they heard going on around them. In making these hypotheses, children were guided by an inbuilt knowledge of language universals. These provided a ‘blueprint’ for language, so that the child would know in outline what a possible language looked like. This involved, first, information about the ‘building blocks’ of language, such as the set of possible sounds. Second, it entailed information about the way in which the components of a grammar were related to one another, and restrictions on the form of the rules. In particular, Chomsky argued that children automatically knew that language involved two levels of syntax – a deep and a surface level, linked by ‘transformations’. And (as he later argued) children also knew about some innately inbuilt constraints on the form sentences could take. With this help a child could speedily sift through the babble of speech he heard around him, and hypothesize plausible rules which would account for it.

Children needed to be equipped with this information, he claimed, because the ‘primary linguistic data’ (the data children are exposed to) was likely to be ‘deficient in various respects’ (1965: 201). It consisted (he controversially assumed) ‘of a finite amount of information about sentences, which, furthermore, must be rather restricted in scope … and fairly degenerate in quality’ (1965: 31).

But another problem arose. There may be more than one possible set of rules which will fit the data. How does a child choose between them? At one time, Chomsky suggested that children must in addition be equipped with an

evaluation

procedure which would allow them to choose between a number of possible grammars, that is, some kind of measure which would enable them to weigh up one grammar against another, and discard the less efficient. This was perhaps the least satisfactory of Chomsky’s proposals, and many psycholinguists regarded it as wishful thinking. There were no plausible suggestions as to how this evaluation procedure might work, beyond a vague notion that a child might prefer short grammars to long ones. But even this was disputed, since it is equally possible that children have very messy, complicated grammars, which only gradually become simple and streamlined (e.g. Schlesinger 1967). So the problem of narrowing down the range of possible grammars was left unsolved.

According to Chomsky (1965 version), then, a hypothesis-making device, linguistic universals and (perhaps) an evaluation procedure constituted an innately endowed Language Acquisition Device (LAD) or Language Acquisition System (LAS), (LAD for boys and LAS for girls, as one linguist facetiously remarked). With the aid of LAD any child could learn any language with relative ease – and without such an endowment language acquisition would be impossible.

Over the years, Chomsky realized that he needed to specify further restrictions on his grammar, of which (he assumed) children were ‘naturally’ aware. Youngsters would know that there were constraints on the ways in which deep structures could be altered by the transformational rules. They would be automatically aware of some quite complex constraints on rearrangement possibilities. For example, consider the sentence:

IGNATIUS HAS STOLEN A PIG.

If we wanted to ask which pig was involved, we would normally bring the phrase about the pig to the front:

WHICH PIG HAS IGNATIUS STOLEN?

But supposing the original sentence had been:

ANGELA KNOWS WHO HAS STOLEN A PIG.

It would then be impossible to bring the ‘pig’ phrase to the front. We could not say:

*WHICH PIG ANGELA KNOWS WHO HAS STOLEN?

According to Chomsky ‘some general principle of language determines which phrases can be questioned’ (1980: 44), and children would somehow ‘know’ this.

However, this relatively straightforward system disappeared from Chomsky’s later writings. What made him change his mind, and what did he propose instead?

CHOMSKY’S LATER VIEWS: SETTING SWITCHES

Suppose children knew in advance that the world contained two hemispheres, a northern and a southern. In order to decide which they were in, they simply needed to watch water swirling down the plughole of a bath, since they were pre-wired with the information that it swirled one way in the north, and another way in the south. Once they had observed a bath plughole, then they would automatically know a whole lot of further information: an English child who discovered bathwater swirling clockwise would know that it had been placed in the northern hemisphere. It could then predict that the sun would be in the south at the hottest part of the day, and that it would get hotter as one travelled southwards. An Australian child who noticed water rotating anticlockwise would immediately realize the opposite.

This scenario is clearly science fiction. But it is the sort of situation Chomsky then envisaged for children acquiring language. They were pre-wired with a number of possible options which language might choose. They would need to be exposed to relatively little language, merely some crucial trigger, in order to find out which route their own language had chosen. Once they had discovered this, they would automatically know, through pre-programming, a considerable amount about how languages of this type work.

Let us consider how Chomsky hit on such an apparently bizarre idea.

Learnability

remained Chomsky’s major concern. How is language learnable, when the crumbs and snippets of speech heard by children could not possibly (in Chomsky’s view) provide sufficient clues to the final system which is acquired? There seemed no way in which the child could narrow down its guesses sufficiently to arrive at the grammar of a human language. The learnability problem has also been called the ‘logical problem of language acquisition’: how, logically, do children acquire language when they do not have enough information at their disposal to do so?

The logical answer is that they have an enormous amount of information pre-wired into them: the innate component must be considerably more extensive than was previously envisaged. Children, therefore, are born equipped with

Universal Grammar

, or UG for short: ‘UG is a characterization of these innate, biologically determined principles, which constitute one component of the human mind – the language faculty’ (Chomsky 1986: 24).

This is ‘a distinct system of the mind/brain’ (1986: 25), separate from general intelligence.

UG was envisaged as more structured than the old and somewhat vaguer notion of innate universals. It was ‘a computational system that is rich and narrowly constrained in structure and rigid in its essential operations’ (1986: 43). Let us see how it differed.

Imagine an orchestra, playing a symphony. The overall effect is of a luscious tropical jungle, a forest of intertwined melodies. Yet, if one looks at the score, and contemplates the various musical instruments, one gets a surprise. Each instrument has its own limitations, such as being confined to a certain range of notes. Most of the instruments are playing a relatively simple tune. The overall, intricate Turkish carpet effect is due to the skilled interaction of numerous simple components.

In 1986, then, Chomsky viewed UG and language as something like an orchestra playing a symphony. It consisted of a number of separate components or

modules

, a term borrowed from computers. Chomsky noted: ‘UG … has the modular structure that we regularly discover in investigation of cognitive systems’ (1986: 146). Within each module, there were sets of principles. Each principle was fairly straightforward when considered in isolation. The principles became complex when they interacted with those from other modules.

The general framework was not at that time entirely new. He still retained the notion of deep and surface structure (or D-structure and S-structure as he started to call them). But the number of transformations was drastically reduced – possibly to only one! But this one, which moved structures about, was subject to very severe constraints. Innate principles specified what could or could not happen, and these were quite rigid. Chomsky’s major concern, therefore, was in specifying the principles operating within each module, and showing how they interacted.

How many modules were involved, and what they all did, was never fully specified. But the general idea behind the grammar was reasonably clear. For example, one module might specify which items could be moved, and how far, as with the word WHO, which can be moved to the front of the sentence:

WHO DID SEBASTIAN SAY OSBERT BIT?

Another might contain information as to how to interpret a sentence such as:

SEBASTIAN SAID OSBERT BIT HIM INSTEAD OF HIMSELF.

This would contain principles showing why SEBASTIAN had to be linked to the word HIM, and OSBERT attached to the word HIMSELF. These two types of principles would interact in a sentence such as:

WHO DID SEBASTIAN SAY OSBERT BIT INSTEAD OF HIMSELF?

Most of the principles, and the way they interleaved, were innately specified and fairly rigid.

However, a narrowly constrained rigid UG presented another dilemma. Why are not all languages far more similar? Chomsky argued that UG was only partially ‘wired-up’. There were option points within the modules, with switches that could be set to a fixed number of positions, most probably two. Children would know in advance what the available options are. This would be preprogrammed and part of a human’s genetic endowment. A child would therefore scan the data available to him or her, and on the basis of a limited amount of evidence would know which way to throw the switch. In Chomsky’s words:

We may think of UG as an intricately structured system, but one that is only partially ‘wired-up’. The system is associated with a finite set of switches, each of which has a finite number of positions (perhaps two). Experience is required to set the switches. When they are set the system functions.

(Chomsky 1986: 146)

Chomsky supposed that the switches must be set on the basis of quite simple evidence, and that a switch, once set in a particular direction, would have quite complex consequences throughout the language. These consequences would automatically be known by the child.

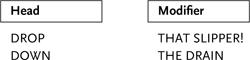

As an example, Chomsky suggested that children might know in advance that language structures have one key word, or

head

. They then had to find out the position of the subsidiary words (or

modifiers

). These could be placed either before or after the head. In English, heads are generally placed before modifiers:

So we get sentences such as:

THE DOG DROPPED THE SLIPPER DOWN THE DRAIN.

A language such as Turkish would reverse this order, and say the equivalent of THAT SLIPPER DROP, THE DRAIN DOWN. The end result is that Turkish looks quite different on the surface. It would say, as it were:

THE DOG THE DRAIN DOWN THE SLIPPER DROPPED.

However, this superficial strangeness is to a large extent the result of one simple option, choosing to place modifiers on a different side of the head.

UG, then, was envisaged as a two-tier system: a hard-wired basic layer of universal

principles

, applicable to all languages, and a second layer which was only partially wired in. This contained a finite set of options which had to be decided between on the basis of observation. These option possibilities were known as

parameters

, and Chomsky spoke of the need ‘to fix the parameters of UG’ (Chomsky 1981: 4). The term

parameter

is a fairly old mathematical one, which is also used in the natural sciences. In general, it refers to a fixed property which can vary in certain ways. For example, one might talk of ‘temperature’ and ‘air pressure’ as being ‘parameters’ of the atmosphere. So in language, a parameter is a property of language (such as head position, discussed above) whose values could vary from language to language.