The Articulate Mammal (24 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

How can one eliminate these possibilities? The answer is that the highly consistent word order made it unlikely that the sequences were random juxtapositions. Whenever Gia seemed to be expressing location she put the object she was locating first, and the location second: FLY BLANKET ‘The fly is on the blanket’, FLY BLOCK ‘The fly is on the block’, BLOCK BAG ‘The block is in the bag.’ When she referred to subjects and objects, she put the subject first, and the object second: GIRL BALL ‘The girl is bouncing the ball’, GIRL FISH ‘The girl is playing with a fish.’ And she expressed possession by putting the possessor first, the possession second: LAMB EAR ‘That’s the lamb’s ear’, GIA BLUEYES ‘That’s Gia’s doll, Blueyes.’ If Gia was accidentally juxtaposing the words we would expect BLANKET FLY or EAR LAMB as often as FLY BLANKET or LAMB EAR. And the possessive sentences make it highly unlikely that Gia was using a ‘topic’ and ‘comment’ construction. It would be most odd in the case of GIA BLUEYES to interpret it as ‘I am talking about myself, Gia, and what I want to comment on is that I have a doll Blueyes.’

Of course, Gia was expressing these relationships of location, possession, and subject–object in the same order as they are found in adult speech. But the important point is that she seemed to realize automatically that it was necessary to express relationships consistently in a way Washoe the chimp perhaps did not. She seemed to

expect

language to consist of recurring patterns, and seemed naturally disposed to look for regularities. But before stating conclusively that Gia’s utterances were patterned, we must consider one puzzling exception. Why did Gia say BALLOON THROW as well as THROW BALLOON when she dropped a balloon as if throwing it? Why did she say BOOK READ as well as READ BOOK when she was looking at a book? Surely this is random juxtaposition of the type we have just claimed to be nonexistent? A closer look at Gia’s early utterances solves the mystery.

In her earliest two-word sequences, Gia

always

said BALLOON THROW and BOOK READ. She had deduced wrongly that the names of people and objects precede action words. This accounts for ‘correct’ utterances such as GIRL WRITE and MUMMY COME as well as ‘mistakes’ such as BALLOON THROW and SLIDE GO, when she placed some keys on a slide. Soon she began to have doubts about her original rule, and experimented, using first one form, then the other. Utterances produced at a time when the child is trying to make up her mind have aptly been labelled ‘groping patterns’ by one linguist (Braine 1976). Eventually, after a period of fluctuation, Gia acquired the verb-object relationship permanently with the correct order THROW BALLOON, READ BOOK.

The consistency which Bloom found in the speech of Kathryn, Eric and Gia, has been confirmed by numerous researchers who have worked independently on other children. In conclusion, then, our answer to the question ‘Are two-word utterances patterned?’ must be ‘Yes’. From the moment they place two words together (and possibly even before) children seem to realize that language is not just a random conglomeration of words. They express each relationship consistently, so that, for example, in the actor–action relationship, the actor comes first, the action second as in MAMA COME, KITTY PLAY, KATHY GO. Exceptions occur when a wrong rule has been deduced, or when a child is groping towards a rule. And even at the two-word stage, children are creative in their speech. They use combinations of words they have not heard before.

However, we have talked so far only about children who are learning English, which has a fixed word order. But some languages have a variable order, and mark grammatical relationships with other devices, such as word endings. How do children cope in these circumstances? The answer varies from language to language (Slobin 1986a). Turkish is a language in which the endings are particularly clear and easy to identify, and Turkish children are reported to adopt consistent endings with variable word order. But in Serbo-Croatian, where word endings are confusing and inconsistent, children prefer

to disregard the endings and use a fixed word order to begin with, even though there is variation in the word order used by the adults around them.

In brief, the evidence suggests that children express relationships between words in a consistent way, whether they use word order or devices such as word endings. This raises a further question: do children from different parts of the world express the

same

relationships? Apparently, children everywhere say much the same things at the two-word stage. Roger Brown noted that ‘a rather small set of operations and relations describe all the meanings expressed … whatever the language they are learning’ (Brown 1973: 198). Because of this similarity, psycholinguists at one time hoped that they might be able to make a definitive list of the concepts expressed at this stage, and predict their order of emergence. But it soon became apparent that there was considerable variation between different children, even when they spoke the same language. Every researcher produced a slightly different list, organized in a slightly different order.

Perhaps the best-known list was that of Brown (1973: 173). He suggested a set of eight ‘minimal two-term relations’, supplemented by three ‘basic operations of reference’, as set out in the chart below.

| Relations | 1 | Agent action | MUMMY PUSH |

| | 2 | Action and object | EAT DINNER |

| | 3 | Agent and object | MUMMY PIGTAIL |

| | 4 | Action and location | PLAY GARDEN |

| | 5 | Entity and location | COOKIE PLATE |

| | 6 | Possessor and possession | MUMMY SCARF |

| | 7 | Attributive and entity | GREEN CAR |

| | 8 | Demonstrative and entity | THAT BUTTERFLY |

| Operations | 9 | Nomination | THIS (IS A) TRUCK |

| | 10 | Recurrence | MORE MILK |

| | 11 | Non-existence | ALLGONE EGG |

The examples here show clearly that young children can cope with different types of meaning relationships. But to what extent do these twoword utterances embody specifically linguistic knowledge? At one time, certain psycholinguists thought that children were born with an inbuilt understanding of some basic grammatical relations. For example, it was claimed that the child who said DRINK MILK showed an innate knowledge of the verb–object relationship (McNeill 1966, 1970). However, most people have now shifted away from this viewpoint. As one researcher noted, the assumption that children understand grammatical relationships in a way comparable to adults is ‘an act of faith based only on our knowledge of the

adult language’ (Bowerman 1973: 187). We must admit that these early utterances do not show any firm evidence of specific linguistic knowledge. They merely reveal an awareness that meaning relationships need to be expressed consistently.

This leaves us with a considerable problem. If we assume that two-word utterances show linguistic knowledge (which would be fanciful) then we have to specify exactly what kind of linguistic grammar we are dealing with. If, on the other hand, we do not regard them as showing evidence of grammar, then we have to find out when children start having a primitive syntax. In this case, we have to assume that language learning is a discontinuous process. Children start with one kind of system, and then shift over to another, syntactic one. We may be dealing with a tadpole-to-frog phenomenon (Gleitman and Wanner 1982), in which the immature tadpole behaves rather differently from the mature frog.

A number of researchers support the notion of discontinuity. Perhaps children initially use their general cognitive ability to express meaning relationships in a consistent way. When they have acquired a certain number, they start to sort them out in their mind. This possibly triggers an inbuilt syntactic capacity. We shall discuss this possible switch-over to syntax in

Chapter 7

.

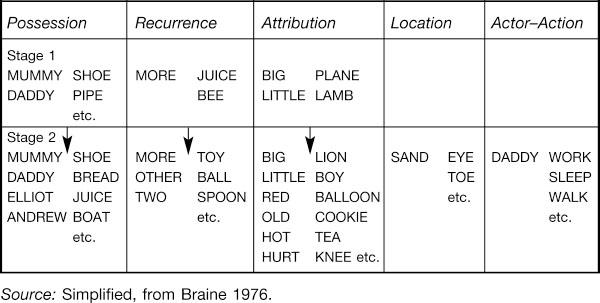

GETTING STARTED

We need to ask a further question. How do children set about acquiring these early utterances? Do they discover how to express one concept at a time? Or do they deal with several simultaneously? A psycholinguist who examined this question was Martin Braine, of pivot grammar fame. Braine found that children coped with several concepts at the same time, but used each one in a very restricted set of circumstances (Braine 1976). For example, just prior to his second birthday, his own son, Jonathan, could express possession, (MUMMY SHOE), recurrence (MORE JUICE) and attribution (BIG DOG), but only with a narrow range of words. In the case of possession, the only possessors were MOMMY and DADDY. Jonathan had apparently acquired a formula for dealing with possession, but a formula of very limited scope, MOMMY or DADDY + object, as in MOMMY SHOE ‘Mummy’s shoe’, DADDY PIPE ‘Daddy’s pipe.’ Jonathan’s formula for dealing with recurrence was even more limited, consisting of the word MORE + object. He used this whenever he wanted more food, as in MORE JUICE, or when he noticed more than one of something, as in MORE BEE. His attribution formula consisted of the words BIG or LITTLE + object, as in BIG PLANE, BIG DOG, LITTLE LAMB, LITTLE DUCK.

Gradually, Jonathan expanded the range of words he used in each formula. Approximately one month later, he had added extra names to his possession formula, as in ELLIOT COOKIE ‘Elliot’s cookie’, ANDREW BOOK ‘Andrew’s

book’. He extended his recurrence formula with the words TWO and OTHER, as in TWO SPOON, OTHER BALL ‘There’s another ball’. He also attributed the colours RED, GREEN, BLUE to objects as in RED BALLOON, as well as the properties OLD and HOT, as in OLD COOKIE, HOT TEA. Somewhat unexpectedly, he also included the word HURT in his attribution formula, producing phrases such as HURT KNEE, HURT HAND, HURT FLY. At around this time he started to express a new concept, that of location, though he restricted the object located mainly to the word SAND, as in SAND EYE ‘sand in my eye’, SAND TOE ‘sand on my toe’. He also began to produce actor–action phrases, in which he usually chose the word DADDY as actor, as in DADDY WORK, DADDY SLEEP. The emergence of Jonathan’s limited scope formulae is set out in the diagram below.

Do all children acquiring language behave like Jonathan? Braine examined the early utterances of a number of other children, and concluded that each one had adopted a ‘limited scope formulae’ approach at the two-word stage, though the actual formulae varied from child to child. Numerous children seem to go about learning language in a roughly similar fashion, even though there is considerable individual variation in the precise track they follow.

However, there may be more variation than Braine realized at the time. It is possible that most of the children studied in the 1960s were subconsciously picked out because they were easy to understand. And they were easy to understand because they fitted in with our preconceptions about what happens as children learn to talk – that they learn single words, then put these words together. But reports then came in of children who do not behave like this. Some learn whole sequences of sounds, then only gradually break them down into words, as with a child called Minh (Peters 1977, 1983). Minh’s

words were often fuzzy and indistinct, but he paid considerable attention to intonation patterns. Over time, his words became separate and distinct, but he did not go through the gradual building-up process found in the speech of many children. As one researcher noted: ‘There is no one way to learn language. Language learning poses a problem for the child, and, as with other complex problems, there is no single path to a solution’ (Nelson 1973: 114).

Where does all this leave us? There is no rigid universal mould into which all early utterances will fit, even though children express the same kind of things at the two-word stage. Moreover, these two-word utterances are patterned in the sense that children express meaning relationships such as actor–action, location and possession consistently. But we have not been able to show that these are essentially grammatical relationships that are being expressed. Consequently, in order to assess the claim that children’s language is patterned in a strictly linguistic sense, we must look at later aspects of language acquisition – at the development of word endings and more complex constructions such as the rules for negation in English.

THE CASE OF THE WUG