The Anatomy of Story (12 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

■ Inherent Weaknesses

Can be the ultimate fascist insisting on perfection, may create a special world where all can be controlled, or simply tears everything down so that nothing has value.

■ Examples

Stephen in

Ulysses

and

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,

Achilles in the

Iliad, Pygmalion, Frankenstein, King Lear, Hamlet,

the master swordsman in

Seven Samurai,

Michael in

Tootsie,

Blanche in

A Streetcar Named Desire,

Verbal in

The Usual Suspects,

Holden Caulfield in

The Catcher in the Rye, The Philadelphia Story,

and

David Copperfield.

Lover

■ Strength

Provides the care, understanding, and sensuality that can make someone a complete and happy person.

■ Inherent Weaknesses

Can lose himself in the other or force the other to stand in his shadow.

■ Examples

Paris in the

Iliad,

Heathcliff and Cathy in

Wuthering Heights,

Aphrodite,

Romeo and Juliet,

Etta in

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Philadelphia Story, Hamlet, The English Patient,

Kay in

The Godfather, Camille, Moulin Rouge, Tootsie,

Rick and Ilsa in

Casablanca, Howards End,

and

Madame Bovary.

Rebel

■ Strength

Has the courage to stand out from the crowd and act against a system that is enslaving people.

■ Inherent Weakness

Often cannot or does not provide a better alternative, so ends up only destroying the system or the society.

■ Examples

Prometheus, Loki, Heathcliff in

Wuthering Heights, American

Beauty,

Holden Caulfield in

The

C

at

c

her in the Rye,

Achilles in the

Iliad,

H

amlet,

Rick in

Casablanca, Howards

E

nd, Madame Bovary, Rebel Without a Cause, Crime and Punishment, Notes from the Underground,

and

Reds.

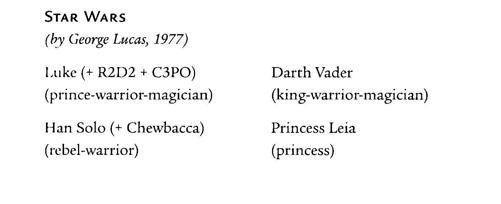

Here is a simple but effective character web emphasizing contrasting archetypes:

IND

IVIDUALIZING CHARACTERS IN THE WEB

Once you have set your essential characters in opposition within the character web, the next step in the process is to make these character func-tions and archetypes into real individuals. But again, you don't create these unique individuals separately, out of whole cloth, with all of them just happening to coexist within the same story.

You create a unique hero, opponent, and minor characters by comparing them, but this time primarily through theme and opposition. We'll look at theme in detail in Chapter 5, "Moral Argument." But we need to look at a few of the key concepts of theme now.

Theme is your view of the proper way to act in the world, expressed through your characters as they take action in the plot. Theme is not subject matter, such as "racism" or "freedom." Theme is your moral vision, your view of how to live well or badly, and it's unique for each story you write.

KEY POINT:

You begin individuating your characters by finding the moral problem at the heart of the premise. You then play out the various possibilities of the moral problem in the body of the story.

You play our these various possibilities through the opposition. Specifically, you create a group of opponents (and allies) who force the hero to deal with the central moral problem. And each opponent is a variation on the theme; each deals with the same moral problem in a different way.

Let's look at how to execute this crucial technique.

1. Begin by writing down what you think is the central moral problem of your story. If you worked through the techniques of the premise, you already know this.

2. Compare your hero and all other characters on these parameters:

■ weaknesses

■ need—both psychological and moral

■

desire

■

values

■ power, status, and ability

■ how each faces the central moral problem in the story

3. When making these comparisons, start with the most important relationship in any story, that between the hero and the main opponent. In many ways, this opponent is the key to creating

the story, because not only is he the most effective way of defining the hero, but he also shows you the secrets to creating a great character web.

4. After comparing the hero to the main opponent, compare the hero to the other opponents and then to the allies. Finally, compare the opponents and allies to one another.

Remember that each character should show us a different approach to the hero's central moral problem (variations on a theme).

Let's look at some examples to see how this technique works.

Tootsie

(by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal, story by Don McGuire and Larry Gelbart, 1982) Tootsie

is a wonderful story to start with because it shows how to begin with a high-concept premise and create a story organically.

Tootsie

is a classic exam-

ple of what is known as a switch comedy. This is a premise technique in which the hero suddenly discovers he has somehow switched into being something or someone else. Hundreds of switch comedies have been written, going at least as far back as Mark Twain, who was a master of the technique.

The vast majority of switch comedies fail miserably. That's because most writers don't know the great weakness of the high-concept premise: it gives you only two or three scenes. The writers

of Tootsie,

however, know the craft of storytelling, especially how to create a strong character web and how to individuate each character by comparison. Like all high-concept stories,

Tootsie

has the two or three funny scenes at the switch when Dustin Hoffman's character, Michael, first dresses as a woman, reads for the part, and triumphantly visits his agent at the restaurant.

But the

Tootsie

writers do far more than create three funny scenes. Working through the writing process, they start by giving Michael a central moral problem, which is how a man treats a woman. The hero's moral need is to learn how to act properly toward women, especially the woman he falls in love with. The writers then create a number of opponents, each a variation on how men treat women or how women allow themselves to be treated by men. For example:

■

Ron, the director, lies to Julie and cheats on her and then justifies it by saying that the truth would hurt Julie even more.

■

Julie, the actress Michael falls for, is beautiful and talented but allows men, especially Ron, to abuse her and push her around.

■ John, the actor who plays the doctor on the show, is a lecher who takes advantage of his stardom and position on the show to force himself on the actresses who work there.

■

Sandy, Michael's friend, has such low regard for herself that when he lies to her and abuses her, she apologizes for it.

■

Les, Julie's father, falls in love with Michael (disguised as Dorothy), and treats her with the utmost respect while courting her with dancing and flowers.

■ Rita Marshall, the producer, is a woman who has hidden her femininity and her concern for other women in order to gain a position of power.

■ Michael, when disguised as Dorothy, helps the women on the show

stand up to the men and get the respect and love they deserve. But when Michael is dressed as a man, he comes on to every woman at a party, pretends to be interested in Sandy romantically, and schemes to get Julie away from Ron.

Great Expectations

(by Charles Dickens, 1861)

Dickens is a master storyteller famous for his character webs. One of his most instructive is

Great Expectations,

which in many ways is a more advanced web than most.

The distinguishing feature in the

Great Expectations

web is how Dickens sets up double pairs of characters: Magwitch and Pip, Miss Havisham and Estella. Each pair has fundamentally the same relationship—mentor to student—but the relationships differ in crucial ways. Magwitch, the criminal in absentia, secretly gives Pip money and freedom but no sense of responsibility. At the opposite extreme, Miss Havisham's iron control of Estella and her bitterness at what a man has done to her turn the girl into a woman too cold to love.

Vanity Fair

(by William Makepeace Thackeray, 1847)

Thackeray called

Vanity Fair

a "novel without a hero," by which he meant a heroic character worthy of emulation. All the characters are variants of predatory animals climbing over the backs of others for money, power, and status. This makes the entire character web in

Vanity Fair

unique. Notice that Thackeray's choice of a character web is one of the main ways he expresses his moral vision and makes his vision original.

Within the web, the main contrast in character is between Becky and Amelia. Each takes a radically different approach to how a woman finds a man. Amelia is immoral by being obtuse, while Becky is immoral by being a master schemer.

Tom Jones

(by Henry Fielding, 1749)

You can see the huge effect that a writer's choice of character web has on the hero in a story like

Tom Jones.

This "picaresque" comic novel has a

large number of characters. Such a big social fabric means the story has a lot of simultaneous action, with little specific depth. When this approach is applied to comedy, truth of character is found in seeing so many characters acting foolishly or badly.

This includes the hero. By making Tom a foolish innocent and basing the plot on misinformation about who Tom really is, Fielding is limited in how much self-revelation and character depth he can give Tom. Tom still plays out a central moral problem, having to do with fidelity to his one great love, but he has only limited accountability.

C

REATING YOUR HERO

Creating a main character on the page that has the appearance of a complete human being is complex and requires a number of steps. Like a master painter, you must build this character in layers. Happily, you have a much better chance of getting it right by starting with the larger character web. Whatever character web you construct will have a huge effect on the hero that emerges, and it will serve as a valuable guide for you as you detail this character.

Creating Your Hero, Step 1: Meeting the Requirements of a Great Hero

The first step in building your hero is to make sure he meets the requirements that any hero in any story must meet. These requirements all have to do with the main character's function: he is driving the entire story.

1. Make your lead character constantly fascinating.

Any character who is going to drive the story has to grab and hold the audience's attention at all times. There must be no dead time, no treading water, no padding in the story (and no more metaphors to hammer home the point). Whenever your lead character gets boring, the story stops.