The Anatomy of Story (16 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

Four-Corner Opposition

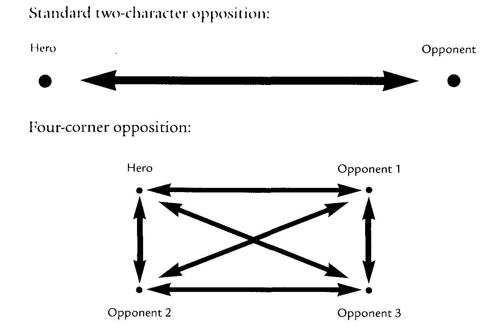

Better stories go beyond a simple opposition between hero and main opponent and use a technique I call four-corner opposition. In this technique, you create a hero and a main opponent plus at least two secondary opponents. (You can have even more if the added opponents serve an important story function.) Think of each of the characters—hero and three opponents—as taking a corner of the box, meaning that each is as different from the others as possible.

There are five rules to keep in mind to make best use of the key features of four-corner opposition.

1. Each opponent should use a different way of attacking the hero's great weakness.

Attacking the hero's weakness is the central purpose of the opponent. So the first way of distinguishing opponents from one another is to give each a unique way of attacking. Notice that this technique guarantees that all conflict is organically connected to the hero's great flaw. Four-corner opposition has the added benefit of representing a complete society in miniature, with each character personifying one of the basic pillars of that society.

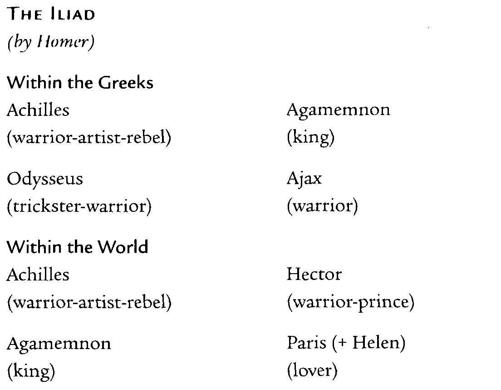

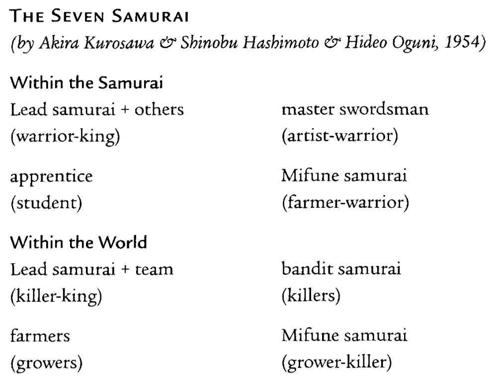

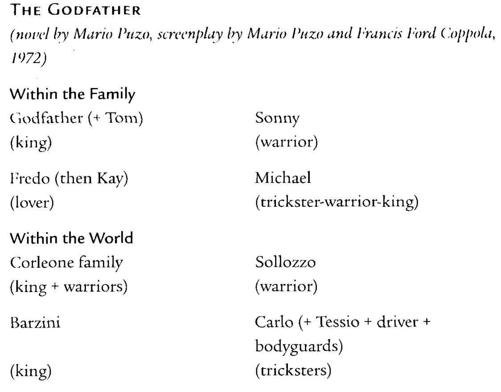

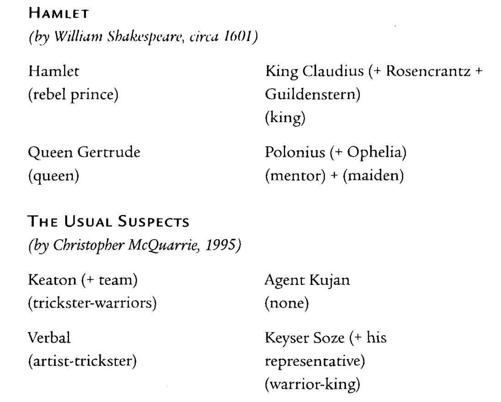

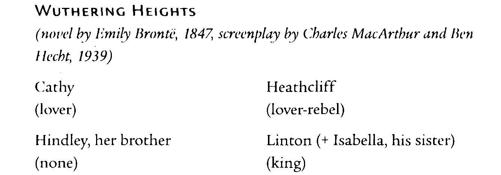

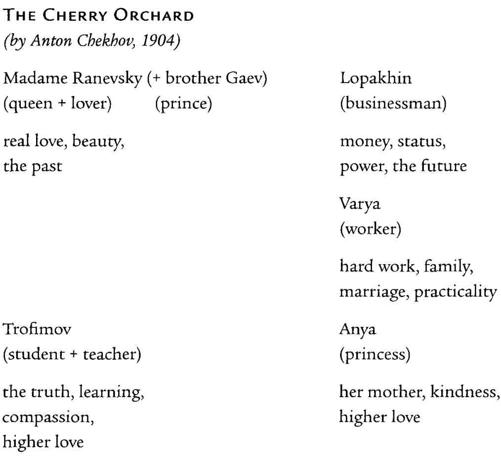

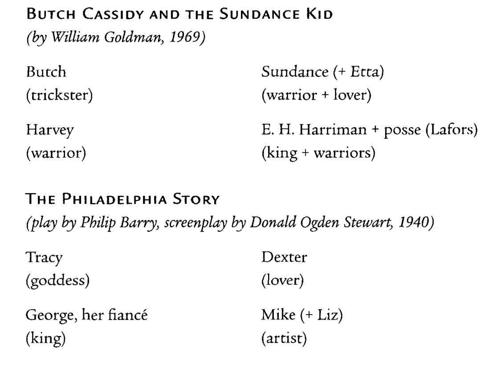

In the following examples, the hero is in the upper left corner, as in the diagram, while his main opponent is opposite him, with the two secondary characters underneath. In parentheses is the archetype each embodies, if one exists. As you study the examples, notice that four-corner opposition is fundamental to any good story, regardless of the medium, genre, or time when it was written.

2. Try to place each character in conflict, not only with the hero but also with every other character.

Notice an immediate advantage four-corner opposition has over standard opposition. In four-corner opposition, the amount of conflict you can create and build in the story jumps exponentially. Not only do you place your hero in conflict with three characters instead of one, but you can also put the opponents in conflict with each other, as shown by the arrows in the four-corner opposition diagram. The result is intense conflict and a dense plot.

3. Put the values of all four characters in conflict.

Great storytelling isn't just conflict between characters. It's conflict between characters

and their values.

When your hero experiences character change, he challenges and changes basic beliefs, leading to new moral action. A good opponent has a set of beliefs that come under assault as well. The beliefs of the hero have no meaning, and do not get expressed in the story, unless they come into conflict with the beliefs of at least one other character, preferably the opponent.

In the standard way of placing values in conflict, two characters, hero and single opponent, fight for the same goal. As they fight, their values and their ways of life—come into conflict too.

Four-corner opposition of values allows you to create a story of potentially epic scope and yet keep its essential organic unity. For example, each character may express a unique system of values, a way of life that can come into conflict with three other major ways of life. Notice that the four-corner method of placing values in conflict provides tremendous texture and depth of theme to a story.

A story with four-corner opposition of values might look like this:

KEY POINT: Be as detailed as possible when listing the values of each

character.

Don't just come up with a single value for each character. Think of a

cluster

of values that each can believe in. The values in each cluster are unique but also related to one another.

KEY POINT: Look for the positive and negative versions of the same value.

Believing in something can be a strength, but it can also be the source of weakness. By identifying the negative as well as the positive side of the same value, you can see how each character is most likely to make a mistake while fighting for what he believes. Examples of positive and negative versions of the same value are determined and aggressive, honest and insensitive, and patriotic and domineering.

4. Push the characters to the corners.

When creating your four-corner opposition, pencil in each character hero and three opponents—into one of four corners in a box, as in our diagrams. Then "push" each character to the corners. In other words, make each character as different as possible from the other three.

5. Extend the four-corner pattern to every level of the story.

Once you've determined the basic four-corner opposition, consider extending that pattern to other levels of the story. For example, you might set up a unique four-corner pattern of opposition within a society, an institution, a family, or even a single character. Especially in more epic stories, you will see a four-corner opposition on several levels.

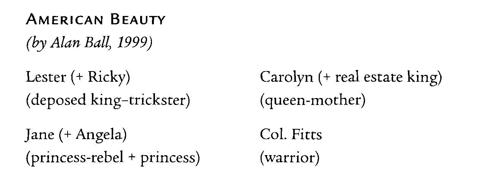

Here are three stories that use four-corner opposition at two different levels of the story.