Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders (24 page)

Read Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders Online

Authors: Jennifer Finney Boylan

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Lgbt, #Family & Relationships, #Parenting, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Gay & Lesbian

TK:

Yeah. If you’re on a game show, you wouldn’t open the second door because you’ve already won the car and the trip to Japan.

JFB:

And yet, I’m moved by this abstract idea of this man out there who has you for a son and doesn’t know.

I mean, who wouldn’t love you?

TK:

You’d be surprised.

“I

NEVER DOUBTED YOU

’

D RISE TO THE TOP

.

Y

OU HAD SUCH A STRANGELY SHAPED HEAD

.”

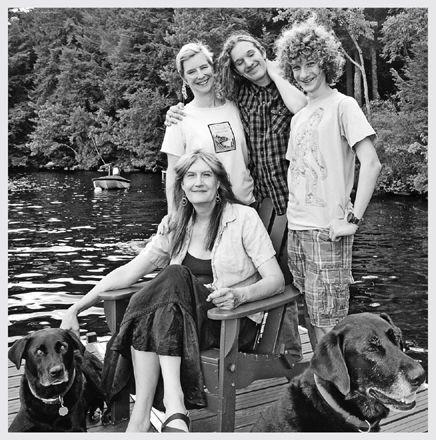

The Boylans, with Ranger and Indigo, on Long Pond, in Belgrade Lakes, Maine, summer 2010

.

© Heather Perry

I opened

my eyes in a dark room. Moonlight reflected off the snow. I went to the bathroom, brushed my hair, swallowed a tiny light green pill. Estrogen dissolved upon my tongue.

I walked down the stairs. The game was afoot. In the basement I split wood for the stove, carried it back up to the kitchen, and got the fire going. I woke up the boys and plugged in the waffle iron, put the bacon in an iron skillet. It was not quite six

A.M

.

I went into the laundry room. Zach’s snow boots were still wet, and I turned on the dryer. The boots thunked and rang inside the drum.

Sean had gotten himself as far as the music room. The sun was just starting to break through the trees, and the early morning light shone off the piano’s raised-up lid.

Zach’s feet clumped up the stairs. A moment later came the rushing of water through the pipes as he turned on the shower.

I put a couple more logs on the woodstove. It was beginning to send out some heat. I removed a waffle from the iron, slung it on a plate. I put this on the table, along with the bacon and a pitcher of pure Maine maple syrup.

“Okay, Seannie,” I said. “Let’s get the day started.”

Sean came into the kitchen and looked at his breakfast and smiled. “It’s Waffle Tuesday,” he said.

At six thirty, Deedie burst into the house with the dogs. “Oh my God is it cold!” she said, her cheeks red, tiny icicles clinging to the bottom of her blue wool hat. The dogs sat down in front of the roaring woodstove and raised their noses in anticipation. Deedie dug into

the giant box of dog biscuits in the cupboard and then gave one to each of the creatures. Then she handed the newspaper—the

Morning Sentinel

—to Sean. “Here’s the paper,” she said. Sean opened the paper to the comics section, where once again Mark Trail was struggling with poachers in Lost Forest.

The dogs crunched their Milk-Bones on the floor. I got up and poured more waffle batter into the iron for Deedie. Zach came bounding into the room, fresh from the shower. “Hi, Mommy. Hi, Maddy. Hi, Sean.” Deedie and I gave him a hug. Sean raised an eyebrow. “Hey, Baby Sean! It’s Waffle Tuesday!”

“Mark Trail is chasing poachers,” said Sean.

“Okay, Boylans,” I said. “What do we got?”

“They have band this afternoon, and Sean’s playing soccer. It’s book group night for me,” said Deedie.

“I’ve got a faculty meeting at four,” I said, “and then I’m supposed to be playing rock ’n’ roll.”

“You have to take Sean to soccer. I told you about book group yesterday.”

“Oh,” said Zach. “I forgot to mention we’re going on a field trip today to the Lobster Museum. I need you to sign some forms. Also, can I have ten dollars? Plus I said we’d bring snacks.”

I pulled Deedie’s waffle out of the iron and put it in front of her. Steam rose toward the ceiling. I poured one for Zach. Deedie looked at the clock. “The school bus is coming in ten minutes,” she said. “I don’t have any snacks for your class.”

“I said you’d bring pumpkin muffins,” said Zach.

“When was it you were going to tell me about this?” said Deedie.

“I just did tell you about this,” said Zach.

“I can’t make muffins now,” she said. “Maybe I can buy some at the store and bring them by the school on my way into work. What time is your field trip?”

“I don’t know,” said Zach.

“Do you have the forms?” said Deedie.

“I think so,” said Zach. He bounced toward the front hallway and opened his backpack. Juice boxes, crayons, notebooks, and rubber balls

rolled onto the floor. “Here it is,” said Zach, holding up a crumpled piece of paper. There was jelly on one corner.

“I can get the muffins,” I said to Deedie, pulling Zach’s waffle out of the iron.

“Will you remember?” said Deedie. It was fairly typical in our family for me to be given tasks that, since they were inherently annoying, I immediately forgot all about, thus saving me from the trouble of having to do them. It was a good system.

“Doubtful,” I said.

“What is the Lobster Museum?” asked Sean. From beneath his chair came the sound of thick black tails slapping against the floor.

“Are you feeding the dogs your waffle?” said Deedie.

“Just the syrup,” said Sean. Pink tongues lapped just out of the range of vision.

“It’s time for everyone to start getting ready,” I said. “I’ll get the muffins and drop them by the school.” Deedie signed Zach’s forms.

“It’s a museum about lobstering,” said Zach. “You’ll see when you’re in fifth grade.”

“So what do they have there? Famous lobsters?” said Sean.

“I said it’s time to get ready,” I said. “Zach, finish your breakfast. Sean, get your things together.”

“It’s about the environment,” said Zach, climbing on his high pony. He took issues of ecology seriously and at that point was determined to devote his life to saving the manatee, a creature not known to have come within five hundred miles of central Maine. “It’s about how to save the lobster’s ecosystem. So the lobsters can have a future!”

Deedie finished her coffee and looked at the clock. “I have to be at work early today,” she said.

“What kind of futures can lobsters have?” asked Sean. “They’re still getting boiled. Aren’t they?”

Zach stuffed an entire waffle into his mouth. “Oink,” he suggested.

Launching children into a Maine winter is not totally unlike preparing them for life at the international space station. On a February day, for instance, the children had to be strapped into enormous snowsuits reminiscent of the various layers of sarcophagi encapsulating

a boy-king of Egypt. Then they had to be equipped with both boots and shoes (they changed out of the boots and into the shoes once at school), high-tech mittens, thermal hats, scarves, earmuffs, backpacks containing all the right books and the completed homework and that day’s permission forms. Sean had to bring his French horn. Both boys needed their music. (Zach, being a tuba player, did not carry his instrument on the bus; according to the school district, a tuba was a fire hazard.)

“I can’t find my boots,” Zach said.

“They’re in the dryer,” I said, and he went into the laundry room and pulled them out and popped them on his feet.

“Woo! Woo!” said Zach. He was hopping and jumping around the house. “Hot shoes!”

“Zach?” I said. “Are you all right?”

Sean looked at me with that ironic grin. “He’s got hot shoes,” he noted.

“Woo! Woo!” said Zach.

“Do you want me to try to find some other boots?” I asked.

“Are you kidding?” said Zach, still dancing. “This is the greatest thing ever! Woo! Woo!

Hot shoes!

Can I have hot shoes every day, Maddy? Please?”

Sean shook his head sadly. There were times when I feared Sean had fallen into the role of Marilyn on the old television show

The Munsters

. This was the one so-called normal child, brought up in a family of Frankensteins and vampires.

“Do you want hot shoes, Baby Sean?” said Zach.

Sean thought it over. “I’m good,” he said.

He

was

good, now anyway. There’d been a season not too long ago, however, when Sean had lain in bed in the morning with tears in his eyes. We’d arranged for him to see a counselor at school, so that he could have someone to talk to about whatever was in his heart. I assumed that whatever was bothering him was a direct result of having me as a parent, but after a few weeks, the therapist said,

Actually, we think the issue is that he hates his math teacher

. In any event the weepy mornings had passed, which of course left his parents relieved. I wasn’t

certain we’d seen the last of the tears, though. I suspected that for the rest of their lives, I’d be waiting to see just how much damage I’d done to my children. I remembered holding Sean in my lap, the week he was born, as he struggled with supraventricular tachycardia.

Seannie, am I never going to stop worrying about you?

The clock struck seven, and I opened the door and walked with the boys bearing their backpacks and French horns, wearing their astronaut clothes, down to the end of our driveway in the shocking Maine cold. Our breath came out in clouds.

We waited for the bus. The sun was now shining through the bare branches to our right; we could hear water moving beneath the frozen ice of the creek that bordered our property on its eastern side. Down the street about a quarter of a mile, we could see our neighbors, the Elliott brothers, waiting at the end of their driveway.

Zach hopped up and down. Sean looked at me knowingly. “That’s my brother,” he said dryly. “He’s got hot shoes.”

“Woo!” said Zach. “Woo!”

The bus came down the hill, and we saw its red lights flashing in front of the Elliotts’ house. This was my cue to leave. Zach turned to me. “You won’t forget the muffins, will you?”

“What muffins?” I said.

“Maddy,” said Zach.

I walked rapidly up the driveway and stood on the porch. The yellow school bus came and the boys stepped on board.

As the school bus pulled away, I made eye contact with an older boy sitting toward the back. He laid eyes upon me, and his features curled into a malicious grin.

Deedie rushed past me.

“You won’t forget the muffins?” she said.

“What muffins?” I said.

“Maddy,” she said. She kissed me on the cheek and then headed toward her car. A moment later, I watched as the minivan turned right out of the driveway and climbed the snowy hill.