Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders (19 page)

Read Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders Online

Authors: Jennifer Finney Boylan

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Lgbt, #Family & Relationships, #Parenting, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Gay & Lesbian

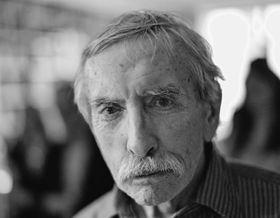

EDWARD ALBEE

Courtesy of Augusten Burroughs

There is no one to tell you who you are except yourself

.

Edward Albee

is an American playwright. A three-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize, as well as a recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the Kennedy Center, he is known for the plays

The Zoo Story, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, A Delicate Balance, Tiny Alice, Three Tall Women, The Goat

, and my own favorite,

Quotations of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung

.

We first met after he saw a play of mine at Johns Hopkins in 1986, a work titled

Big Baby

, which was a short dramatic piece about a baby that gets really big. After the play, Albee stood up in the audience and asked me, “Mr. Boylan. Could you please explain—why is the baby—so large?”

Edward was adopted at birth by a couple he calls “those people.” We met at his loft in New York—a beautiful space filled with modern and impressionist paintings and primitive sculptures—to talk about waifs, orphans, angels, and imagination. Albee being Albee, of course, he started asking me questions the moment I stepped through the door.

E

DWARD

A

LBEE:

What is the need to make this distinction between being a father and a mother?

J

ENNIFER

F

INNEY

B

OYLAN:

[

Sitting down on couch

] Well, it may be that there is no distinction. That’s one of the things I’m exploring, Edward. I know that my sense of the world is different, but it may be

less about the difference between male and female than the difference between someone who is bearing a secret and someone who is not.

EA:

I guess I’m really asking because it seems to me in some way that you are less different to your sons because you’re the same person.

JFB:

There’s definitely a before and an after in my life. For them, the before is such a long time ago. So their memories of me as a man—

EA:

Can you think about being a father? You must remember very specifically their birthing. And your response as a father, yes?

JFB:

Yes.

EA:

Was it more complicated than that?

JFB:

My response was astonishment at the otherworldliness of it. And joy and concern for the woman that I love. I was hoping she was all right.

EA:

When they were born, did you have any intimations of what might be going on later?

JFB:

I hoped it would not come to that.

EA:

So that must have affected your response to being a father.

JFB:

My fear that this would come to pass?

EA:

Mm. Well, not fear, but concern.

JFB:

Well, there are all kinds of dads, including ones like me who were better known for making a good risotto than being able to throw a football.

EA:

But when they were born, you were a guy.

JFB:

I was.

EA:

Therefore, you were their father.

JFB:

Am I or was I?

EA:

You haven’t become their mother.

JFB:

Well, I’m their sire.

EA:

Yeah. So, you are a parent. I just wonder, aside from all sorts of things, what difference it really makes.

JFB:

Well, maybe none. Perhaps none. Perhaps what’s more important than us being male or female is the fact that we’re human. I’m comfortable with that.

EA:

You see, if you’re a father it means you’ve had sex with a woman, your wife or someone else, and impregnated her.

JFB:

You think that’s what it means? Seriously?

EA:

You never birthed those two. Isn’t that a different quality of parenthood?

JFB:

I think it is. On the other hand, I know gay men who have adopted children and neither father gave birth to the child.

EA:

Well, that’s very, very complex.

JFB:

Well, yeah. Welcome to my world, Edward.

EA:

Ten weeks of discussion. My God.

JFB:

We don’t have ten weeks.

EA:

I’m getting awfully concerned about so many of my gay friends who are adopting kids. I’m getting very worried about them. They don’t know what they’re getting into.

JFB:

What are they getting into?

EA:

They’re getting into a long-term thing, a very long-term thing that I don’t think that they ever anticipate.

JFB:

Why should they not be able to understand a long-term commitment any more than a straight couple? Straight couples can be just as blind.

EA:

Because it has nothing to do with sex. If neither of you is the parent, neither gay guy is the parent, is a parent of the offspring, then all the rules are off.

JFB:

But are they not the parents? Does parenthood have to mean biology?

EA:

Does it mean making or is it the being?

JFB:

I think it’s the being.

EA:

Yeah. Well, what do we do about the making then? You made two boys. Through your own need and choice, you have become their mother rather than their father, but you’re still their father.

JFB:

Well, even if that’s true—which I’m not sure it is—it makes me a very different kind of mother than most other women I know. And it makes me different from most of the fathers I know. And yet, my experience as their mother, as their parent, has been more universal than—absurd.

EA:

Do you find that you think about them differently as a woman than you did as a man?

JFB:

Well, I think as a father I was a little bit more feckless. I just wanted to make them laugh. I was very goofy and I would do these ridiculous stunts and things to make them laugh. I loved hearing that.

As a mother, I keep after them a lot more. I nag them more, sometimes—

EA:

You’re behaving like a woman. [

Laughter

] But do you think about them differently?

JFB:

I worry about them more. Because they’ve had a parent who is so different.

EA:

When you look at them now do you ever say to yourself, “I am their father”?

JFB:

No.

EA:

But you are. You’re also their mother.

JFB:

It’s a long way from Tipperary, but we came from there. It’s also the trick of memory. Trying to remember who we have been.

EA:

And what we choose to remember, yes.

JFB:

I try to remember who was I when I was your student in 1986—that frightened, hopeful scarecrow of a boy.

EA:

You were also cute.

JFB:

Was I?

EA:

Yeah. [

He smiles wistfully

.]

JFB:

Well, look who’s talking.

Do you remember those long talks we used to have about James Thurber?

EA:

I don’t know why people don’t read Thurber anymore.

JFB:

Sometimes I think it’s just down to you and me. I was thinking about how, when I was a thirteen-year-old transsexual on the Main Line of Pennsylvania, I wanted to be James Thurber. That’s who I dreamed of being, of all of the artists that I could have chosen to be. It seems so strange to me now.

EA:

There are so many things that I admire about Thurber’s work. I thought he was an extraordinary prose stylist, among other things. I found those few very, very, very serious old-fashioned stories that he wrote quite amazing.

JFB:

“The Cane in the Corridor.” And “One Is a Wanderer,” in

which that sad, lonely protagonist walks around singing “Bye, Bye, Blackbird” to himself. I got to play “Bye, Bye, Blackbird” on Thurber’s piano at the Thurber House in Columbus. I felt rather cheeky doing it.

EA:

Nobody could be funnier than Thurber when he was being funny.

JFB:

He was funny, but you also felt this kind of smoldering anger and resentment. Was it the blindness? I think what I related to in Thurber was that as a young transgender person so deeply in the closet, I felt that my problems were fundamentally unresolvable. But that there was a way of getting along in the world and that my sense of humor was going to help me. Writing was going to help me too, but I would never have a sense of resolution in my life, or so I believed back then. As a young man did you feel that your situation in the world was unresolvable?

EA:

I had no problem. Look, remember. I didn’t belong with those people that adopted me. They had nothing to do with me. I had nothing to do with them. We were together through contract.

JFB:

The thing I can’t get my mind around is their son was—Edward Albee. How could they not have been grateful?

EA:

That wasn’t the one they bought. They bought something they could turn into what they could tolerate. And ended up with me instead.

JFB:

Well, who did they want?

EA:

They wanted somebody who probably would be a businessman, certainly would carry on the family and all that—family name—and give them grandchildren and things like that. The entire family was sterile. The mother of the sister, my father’s sister, couldn’t have any kids, nor could he. I don’t really know who was lacking there. Both of them perhaps. I don’t know. But I know that the grandfather, old EF, he wanted a grandson. That’s why I turned up.

JFB:

Your biological parents were Louise Harvey and an unnamed man. Who do you imagine they might have been?

EA:

I don’t know. That’s the only thing that bothered me about being adopted in the days when you couldn’t find out that sort of thing. I would like to know where I got my odd mind from.

JFB:

Do you think that your odd mind came from them or do you think that you invented it yourself?

EA:

Well, it must have come in part, probably more from him than from her. Maybe not.

JFB:

Because oddness of mind is a thing that fathers give us?

EA:

No, I just think maybe because I was a guy that I turned out to be so unlike other guys. Must be in my father’s personality. But then again I was surrounded by men who were more passive and women who were more—

JFB:

Characters.

EA:

Yeah, characters. And aggressive. When I was told that I was adopted my feeling was relief. I’m not these people. I don’t owe these people anything. I never felt like I belonged there.

JFB:

But it’s funny, Edward. I was not adopted. I was the son of a Main Line banker and his very sweet wife and yet, I didn’t think I was related to them either. I often fantasized who were my real parents. That I must have been adopted somehow.

EA:

Maybe the basic difference is, there are some of us who want to find out—create ourselves—and others who wish to be whatever they want us to be.

JFB:

And we created ourselves. I guess that’s the thing about wondering about your biological father. If it turned out, somehow, that he was actually George M. Cohan—

EA:

Then he’d have a lot to apologize for.

JFB:

Who would he have been? Have you imagined, given that you are known for invention—?

EA:

I just think he would have been interesting. It ties into my great love for that line from “Knoxville” from James Agee’s book. “Finally I am put to bed. Sleep, soft smiling, draws me unto her: and those that receive me, who quietly treat me, as one familiar and well-beloved in that home: but will not, oh will not, not now, not ever, but will not ever tell me who I am.”