Stranded (A stand-alone SF thriller) (The Prometheus Project Book 3) (7 page)

Read Stranded (A stand-alone SF thriller) (The Prometheus Project Book 3) Online

Authors: Douglas E Richards

“Well I think

yogurt

is disgusting,” he replied, biting off the top portion of the brown lump loaded with countless bits of chopped up peanuts.

“Do you want to hear this or don’t you?” said Mr. Resnick pointedly. He waited for both kids to give him their full attention and then began. “Okay, here we go. But I warn you. You’ll be pulling your hair out before I’m through and your brain will hurt. Don’t expect to understand everything I’m about to tell you. Believe me,

I

don’t fully understand everything I’m about to tell you.” He paused. “So what is a dimension in the first place?” he asked. “How would you even define the word?”

Both kids thought about this for a while. Finally Regan shrugged. “I don’t know. Something you can measure?” she said uncertainly.

“Okay,” said Mr. Resnick. “Something you can measure. That’s a reasonable definition, and as good a place to start as anywhere. So a line represents one dimension. Because you can only measure

one

thing about it: its length. That’s all. It doesn’t have any width or height. So then what figure would represent two dimensions?”

“A square,” said Ryan.

“Yes. Any flat shape would do, but a square works well. You can measure its length and width. But it still doesn’t have any height. So what figure would have three dimensions?”

Regan swallowed a spoonful of yogurt that the strawberries had turned pink. “A cube,” she replied. “You can measure three things. Its length, its width and its height.”

“Good,” said her father. “So these are the three dimensions we can perceive in our universe. And while you

can think of a dimension as something you can measure, you can also think of dimensions as directions you can travel in. So let’s imagine for a moment that Brewster, Pennsylvania is the entire world.”

Ryan and Regan both groaned at the same time. “Are you trying to give us nightmares, Dad?” said Ryan with a grin.

Mr. Resnick laughed. “How about San Diego, California?”

“Now you’re talking,” said Regan.

“Okay,” said their father. “Suppose you were a conductor on a train going due north through San Diego. How many different directions could you go in?”

Regan tilted her head in thought. “Only one,” she said, wondering if this was a trick question. “You’d have to stay on the train track. So you could only go north.”

“Right. You can think of the train track as a line. A one-dimensional figure. And your options for travel in a one-dimensional world are extremely limited.” He paused. “Now let’s suppose you’re driving an off-road vehicle in the center of San Diego. What directions could you travel in?”

“Any direction you wanted to,” said Ryan. “North, south, east or west. Or anything in between.”

“That’s right. So the flat city of San Diego is like a two-dimensional figure. And you have

lots

of options for traveling in this two-dimensional world. Just adding a single dimension gives you a lot more freedom to

move, doesn’t it?” He paused once again to give the kids time to digest this idea. “Now suppose you’re piloting a

helicopter

in the center of the city. What directions could you travel in now?”

“Well, you could travel north, south, east and west,” said Regan.

“And

up and down. And anywhere in between.”

“You’ve got it,” said Mr. Resnick. “So obviously, San Diego and the airspace above it represent a 3D figure. And once again, you have far more directions you can travel in.”

Mr. Resnick paused. “Okay,” he said. “So far this has been fairly simple. But it gets impossibly hard very quickly. Don’t worry if you don’t understand the rest of this. No one really does. Not completely. But I’m hoping you understand enough of it to at least get a sense of the possibilities.” He raised his eyebrows. “So what is the fourth dimension? And while ‘time’ can be considered a dimension, that’s not what I mean. I mean the fourth dimension of space.”

Both kids just stared at him blankly. Ryan even lowered his second mountainous spoonful of peanut butter to his side, and away from his mouth, for this first time.

“Well,” said their father. “Maybe we should review. To go from the first-dimension to the second, you have to move in a side to side direction. And to go from the second to the third, you have to move in an up and down direction. So what direction would you have to move in to get to the fourth dimension?”

They thought about this for about thirty seconds before giving up in total frustration.

“I think you’ve lost your mind, Dad,” said Ryan.

“Ryan’s right,” said Regan, taking a sip from the plastic water bottle in her hand. “There isn’t a fourth dimension. It’s a trick question. The universe ran out of dimensions after three.”

“You may be right,” said her father. “But then again, one of the most popular theories in modern physics suggests there are as many as 10 or 11 dimensions.” He smiled. “So I’ll tell you the answer. You would have to move in a direction that no human has ever been able to visualize. A direction that no human has ever moved in. A direction that isn’t north, south, east or west. Or up and down. Or anything in between.”

Ryan frowned. “There

is

no such direction,” he said in annoyance. “It’s ridiculous.”

“Just because we can’t imagine such a direction doesn’t necessarily mean it doesn’t exist. But even if we can’t visualize the fourth dimension, there are still ways we can understand some of its properties. Understand how beings living there would interact with us—with poor humans that can only sense three dimensions.”

Ryan shook his head. “I’m still going with the ‘you lost your mind’ thing,” he said.

Their father looked amused. “The best way to grasp some of the possibilities,” he said, “is to try a thought experiment.”

“A thought experiment?” repeated Ryan questioningly.

“Yes. An experiment you do in your mind only. Using nothing but your imagination. It’s an enormously powerful tool in physics. Some of Einstein’s greatest breakthroughs were the result of using this technique. The thought experiments we’ll be doing first appeared in a book written by an English schoolmaster, Edwin Abbott, in 1884. A book called

Flatland

.

“Abbott figured the best way to understand how we would appear to fourth dimensional beings,” continued Mr. Resnick, “is to think about how beings living in

lower

dimensions would appear to

us

. So he imagined a kingdom that existed in a universe with only one dimension. He called this Lineland. And he imagined a kingdom that existed in a universe with only two dimensions. He called this Flatland.”

Mr. Resnick raised his eyebrows. “So if there were a kingdom of people that existed in a universe with only one dimension, what would that kingdom be like?”

The siblings looked at each other perplexed. “I have no idea,” said Ryan for them both.

“Well, in Lineland, all the inhabitants would be line segments. And they could never change their order. Here, I’ll show you what I mean.”

He picked up a black marker and pulled off its cap with a loud pop. He went to the whiteboard and began writing squeakily.

Ben Resnick gave his kids a few seconds to digest his drawing and then, pointing to the line segment labeled, “The Queen,” he continued. “For example, if you were the Queen, you’d be stuck between the Court Jester and the King.

Forever

. Without any width dimension you couldn’t pass anyone—if you tried you would just slam into them. Like two trains trying to pass each other on the same track. Now if you could make use of the second dimension—move side to side—you could just move to a different track, so to speak, and easily get by. But a Linelander can’t. Their entire universe exists on a single line and they have no awareness of anything outside of this line.”

Mr. Resnick capped the marker and slid it onto the tray at the bottom of the whiteboard. He motioned to his desk. “I’m not a very good artist, so let’s move to my computer,” he said.

They walked a few yards to his glass-topped desk, on which sat a sleek laptop computer connected to a thirty-six inch monitor. In less than a minute of searching he found a cartoon drawing that would demonstrate his point and put it up on the screen.

Both kids smiled broadly and barely managed not to laugh when they saw it.

“Dad couldn’t draw that?”

broadcast Ryan.

“Really?”

“We’re lucky Dad has such a powerful computer,”

replied Regan sarcastically.

“So this brings us to Flatland,” continued Mr. Resnick, unaware that his kids were teasing him telepathically. “Flatland exists in a 2D universe. So think of Flatland as a giant piece of flat notebook paper. And Flatlanders—who appear as circle-people in the figure—are totally, well …

flat

. Flatlanders have no idea there is such a thing as up or down. They can only look and move in sideways directions. So if a Flatland dad suggested to his kids there might be another direction to move in, other than back and forth and sideways, they would tell him he was crazy. Impossible, they would say.

There is no such direction, they would say. To us 3D beings, the up direction is obvious. But to the poor 2D Flatlanders, no matter how much you told them about the up direction and described what it was like, they couldn’t even

begin

to imagine it.”

“Like we can’t even begin to imagine what direction the fourth dimension would be in,” said Regan.

“Exactly,” said Mr. Resnick happily. “And since their universe exists in only two dimensions, Flatlanders are completely unable to lift themselves off the page. Not even a billionth of an inch. Just like we’re unable to move even a billionth of an inch in the direction of the fourth dimension. Whatever direction

that

is. But unlike people living in the line universe, at least Flatlanders can move

past

each other.”

Regan raised her eyebrows. “That must be a relief,” she said playfully.

Regan dropped her empty yogurt container and spoon into a small wastebasket nearby. Ryan decided he was done eating also and did the same with his spoon, screwing the lid closed on the jar he had been holding and setting it down on one of the few empty spaces on his father’s desk.

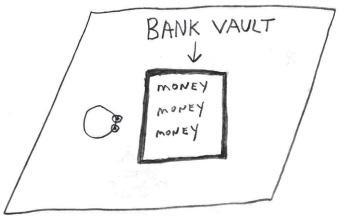

Ben Resnick walked to the whiteboard once again and motioned for his kids to follow. “The key point is that the fewer dimensions you perceive and can operate in, the more limited you are.” He hastily drew another diagram on the board.

“So here you see a Flatlander eyeing a bank vault.”

“How is that a bank vault?” protested Ryan. “It’s just a square. And it’s not enclosed.”

“Good point,” said Mr. Resnick. “It doesn’t have a roof. Why do you think that is?”

Regan’s eyes widened. Could it be that this was finally beginning to make some kind of bizarre sense to her? “Because it

can’t

have a roof,” she said. “Because you can’t have any height in Flatland. A roof has to go

over

something. But there is no such thing as over or under in Flatland.”

“You’ve got it,” said her father. “But it doesn’t need a roof. Flatlanders have no way to see what’s inside the vault. And they can’t climb over the line blocking them from the money. So unless they can break through one of the walls there is no way they can get into this vault. But

we

live and move in the third dimension. So we could get the money.

Easily

,” he said. “We could just reach in from above and grab it. Everyone in Flatland would think the theft was impossible. Like magic. But what seems impossible in one dimension can be laughably easy in a higher dimension.”