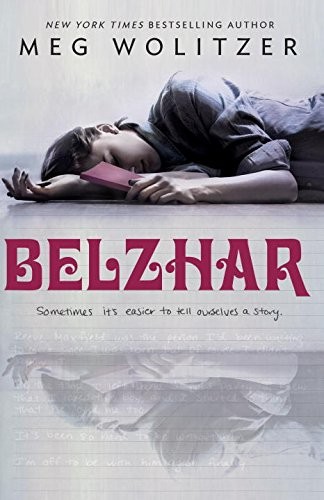

Belzhar

Authors: Meg Wolitzer

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Depression & Mental Illness, #Death & Dying, #Girls & Women

DUTTON BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA * Canada * UK * Ireland * Australia

New Zealand * India * South Africa * China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Meg Wolitzer

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

CIP Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-101-60027-6

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their contents.

Version_1

For my sons, Gabriel and Charlie

PROLOGUE

I WAS SENT HERE BECAUSE OF A BOY. HIS NAME

was Reeve Maxfield, and I loved him and then he died, and almost a year passed and no one knew what to do with me. Finally it was decided that the best thing would be to send me here. But if you ask anyone on staff or faculty, they’ll insist I was sent here because of “the lingering effects of trauma.” Those are the words that my parents wrote on the application to get me into The Wooden Barn, which is described in the brochure as a boarding school for “emotionally fragile, highly intelligent” teenagers.

On the line where it says “Reason student is applying to The Wooden Barn,” your parents can’t write “Because of a boy.”

But it’s the truth.

When I was little I loved my mom and dad and my brother, Leo, who followed me everywhere and said, “Jammy,

wait.

” When I got older I loved my ninth-grade math teacher, Mr. Mancardi, even though my math skills were deeply subnormal. “Ah, Jam Gallahue, welcome,” Mr. Mancardi would say when I came to first period late, my hair still wet from a shower; sometimes, in winter, with the ends frozen like baby twigs. “I’m tickled that you decided to join us.” He never said it in a nasty tone of voice. I actually think he was tickled.

I was in love with Reeve in a fierce way that I’d never been in love with anyone before in all my fifteen years. After I met him, the kinds of love I’d felt for those other people suddenly seemed basic and lame. I realized there are different levels of love, just like different levels of math. Down the hall in school back then, in Advanced Math, a bunch of geniuses sat sharing the latest gossip about parallelograms. Meanwhile, in Mr. Mancardi’s Dumb Math, we all sat around in a math fog, our mouths half open as we stared in confusion at the ironically named Smart Board.

So I’d been in a very dumb

love

fog without even knowing it. And then, suddenly, I understood there was such a thing as Advanced Love.

Reeve Maxfield was one of three tenth-grade exchange students, having decided to take a break from his life in London, England, one of the most exciting cities in the world, to spend a semester in our suburb of Crampton, New Jersey, to live with dull, cheerful jock Matt Kesman and his family.

Reeve was different from the boys I knew—all those Alexes, Joshes, and Matts. It wasn’t just his name. He had a look that none of them had: very smart, slouching and lean, with skinny black jeans hanging low over knobby hip bones. He looked like a member of one of those British punk bands from the eighties that my dad still loves, and whose albums he keeps in special plastic sleeves because he’s positive they’re going to be worth a lot of money someday. Once I looked up one of my dad’s most prized albums on eBay and saw that someone had bid sixteen cents for it, which for some reason made me want to cry.

The covers of my dad’s albums usually show a bunch of ironic-looking boys standing together on a street corner, sharing a private joke. Reeve would have fit right in. He had dark brown hair swirling across a pale, pale face, because apparently there’s no sunlight in England. “Really? None? Total darkness?” I’d said when he insisted this was true.

“Pretty much,” he’d said. “The whole country is like a big, damp house where the electricity’s been turned off. And everyone’s lacking vitamin D. Even the queen.” He said all this with a straight face. There was a

scrape

to his voice. And though I don’t have any idea what people thought of him back in London, where that kind of accent is ordinary, to me his voice sounded like a lit match being held to the edge of a piece of brittle paper. It just exploded in a quiet burst. When he spoke I wanted to listen.

I also wanted to look at him nonstop: the pale face, the brown eyes, the flyaway hair. He was like a long beaker in chemistry class, and the top was always bubbling over because some interesting process was taking place inside.

I’ve now compared Reeve Maxfield to both math and chemistry. But in the end the only class that came to matter in all of this was English. It wasn’t my English class at Crampton Regional; it was the one I took much later, at The Wooden Barn up in Vermont, after Reeve was gone and I could barely live.

For reasons I didn’t understand, I was one of five students tapped to be in a class called Special Topics in English. What happened in that class is something that none of us have ever talked about to anyone else. Though of course we think about it all the time, and I imagine we’ll think about it for the rest of our lives. And the thing that amazes me the most, the thing I keep obsessing about, is this: If I hadn’t lost Reeve, and if I hadn’t been sent away to that boarding school, and if I hadn’t been one of five “emotionally fragile, highly intelligent” teenagers in Special Topics in English, whose lives had been destroyed in five different ways, then I would never have known about Belzhar.

CHAPTER

“JESUS, JAM, YOU’D BETTER GET UP ALREADY,” SAYS

my roommate, DJ Kawabata, an emo girl from Coral Gables, Florida, with “certain food issues,” as she put it vaguely. She looms over my bed, her black hair hanging in my face. Because of DJ, our room is a treasure hunt of hidden food: Twizzlers, granola bars, boxes of raisins, even a squeeze bottle of some off-brand of ketchup called, I think,

Hind’s

, as if the company hoped that people would get confused and buy it. All of it has been planted strategically for so-called emergencies.

I’ve been living at The Wooden Barn for only one day, and I haven’t witnessed one of my roommate’s emergencies yet, but she assures me they’re coming. “They always come,” she’d said, shrugging, when she first tried to explain what it would be like to share a room with her. “You’re going to see some shit you wish you’d never seen before. But don’t worry, I’m talking

figurative

shit. I’m not seriously unhinged.”

“Seriously unhinged” doesn’t get admitted to The Wooden Barn. This place isn’t a hospital, and they make a big point of how they’re against giving out psychiatric medication. Instead, they insist that the school experience is meant to bring people together and help them heal.

I can’t imagine that this can be true. They don’t even let you have the Internet. They ban it completely, which just seems cruel. They also confiscate your cell phone. There’s one ancient pay phone in the girls’ dorm, and one in the boys’. There isn’t any accessible Wi-Fi, so you can use your laptops for writing papers, but you can’t research anything. You can listen to music, but you’re out of luck if you want to go online and download new songs. You’re cut off from everything, which makes no sense at all, because everyone at this school is already cut off in one way or another.

Although no one comes right out and says it, The Wooden Barn is sort of a halfway house between a hospital and a regular school. It’s like a big lily pad where you can linger before you have to make the frog-leap back to ordinary life.

DJ told me she’d previously been in a special hospital for eating disorders. The patients there were all girls, she went on, and they were constantly being weighed by nurses who wore those pediatric nurse blouses that had patterns of cutesy puppies or panda bears on them. Sometimes when their weight got too low, the girls were force-fed through tubes.

“That happened to me once,” DJ said. “One of the nurses held me down, and her boobs were smashed into my face, and when I looked up, all I could see was an ocean of tiny golden retrievers.”

By the time I arrive at The Wooden Barn, DJ has been here for two years. And this morning, on the very first day that classes begin, as she hovers above me with her hair hanging in my face like a curtain, I just want her to go away. But she won’t.

“Jam, you already missed breakfast,” she says, as if she’s my parent or something. “It’s time for class. What’ve you got first?”

“No idea.”

“Haven’t you looked at your skedge?”

“My

‘skedge’

? If you mean my schedule, no.”

I’d arrived the day before, having made the six-hour drive up with my parents and Leo. My mom was sort of crying the whole way but pretending it was allergies, and my dad was listening to NPR with a strange intensity. “Today,” said the woman on the radio, “we are going to devote our entire show to the voices suppressed by the Taliban.”

My dad turned up the volume and nodded his head thoughtfully, as if it were the most fascinating thing, while my mom closed her eyes and cried, not about the voices suppressed by the Taliban, but about me.

My brother, Leo, was just being himself, sitting beside me pressing buttons on the grimy little handheld in his lap. “Hey,” he said when he’d beaten a level of his game and caught my eye.

“Hey.”

“It’ll suck without you in the house.”

“You’d better get used to it,” I said to him. “Our childhood together is pretty much over.”

“That’s mean,” he said.

“But it’s true. And then eventually,” I went on, “one of us will die. And the other one will have to go to the funeral. And give a speech.”

“Jam,

stop

,” Leo said.

I immediately felt sorry about what I’d said, and didn’t even know why I’d said it. I was in a bad mood all the time. Leo didn’t deserve to be treated this way. He was only twelve, and he looked even younger. Some kids in his grade looked like they were ready to have children; Leo looked like one of the children they might’ve had. Occasionally he got tripped in the hall, but nothing really bothered him because he’d found a way not to care. From the time he turned ten, he’d been obsessed with the alternative world of a video game called

Dream Wanderers

that has to do with magic cubes and apprentices and characters called driftlords.

I still have no idea what a driftlord is. At the time, I didn’t even understand what an alternative world was, but now of course I do. And so I get what my little brother has known for a while: Sometimes an alternative world is much better than the real one.

“I wasn’t trying to be mean,” I told Leo in the car. “I get like this,” I added.

“Mom and Dad told me that when you act this way I should just let it go, because—”

“Because why?” My voice had an edge.

“Because of what you’ve been through,” he said uneasily. He and I had barely talked about it. He was so young, and he couldn’t possibly know what I’d been through, what I’d felt.

The conversation had nowhere to go, so we each looked out our separate windows, and finally Leo closed his eyes and went to sleep with his mouth open. The car was enveloped in the smell of the cool-ranch-flavored chips he’d been eating. I felt sorry for him that he was like an only child now. That he no longer had a normal older sister. That instead he had one who’d become destroyed enough to have to go live at a special school in another state six hours away.

Drop-off at The Wooden Barn was highly tense. My mom kept trying to arrange my room, while DJ lounged on her bed, silently watching the whole scene, clearly amused by it.

“Be sure you give your study buddy a couple of big punches every day so the filling stays even,” my mom said to me as I put things in drawers.

From my trunk, I took out the jar of Tiptree Little Scarlet Strawberry Preserve, the jam that Reeve had given me the night we first kissed, and I held the cool glass cylinder in my hand for a moment. I knew I’d never open this jar. It was almost like an urn that had Reeve’s ashes in it. The seal would remain unbroken forever. The jar was sacred to me, and I deposited it in my top dresser drawer and covered it carefully with a mess of bras and underwear and an old Tweety Bird nightshirt.

“Just reach out and hit it, okay, Jam?” my mom continued. “Just hit it like it was a predator who’s jumped you in an alley.”

“Mom,”

I said, while DJ kept watching, not even pretending she wasn’t. She annoyed me so much, and I couldn’t believe I was going to have to live with her.

“I mean, just give it a good slug all around the bottom and the sides,” my mom continued, demonstrating how I should attack the so-called study buddy, that big pillow with arms that she’d insisted we buy for my room at the Price Cruncher back in Crampton.

The woman at the checkout counter had smiled at us when we managed to hoist it onto the moving belt. And then she’d said in a singsong voice, “Is someone going to Fenster Academy?”

Fenster Academy is the snotty boarding school not too far from my house in New Jersey where the girls have horses and everyone wears a sky-blue uniform, and sings these corny songs with bad rhymes like, “Oh Fenster, dear Fenster, we will ne’er forget our semesters . . .” Mom and I both awkwardly shook our heads no.

The study buddy was enormous, orange, and corduroy. I hated it in the store, and I hated it again when it sat on my bed in The Wooden Barn with its arms out. I even hated the name “study buddy.” Everyone knew I was still in no condition to study.

Apparently, though, it was time to “knuckle down,” or “get with the program,” as people said. And since I couldn’t do that, then it was time for me to enroll at The Wooden Barn, where supposedly a combination of the Vermont air, maple syrup, no psychiatric medication, and no Internet will cure me. But I’m not curable.

The other thing that makes the name “study buddy” awful is that I have no “buddies” anymore. Before I met Reeve and wanted to be with him all the time, my closest friends in Crampton were two other low-key, nice girls with long, straight hair—girls like me. We worked hard at school but weren’t nerds, and had done a little weed but weren’t stoners. Mostly we were all considered cute-looking and sweet and sort of shy.

Actually, I don’t think anyone thought about us all that often. We were the kind of girls who braided one another’s hair when we were younger, and practiced synchronized dance moves, and slept over at one another’s houses every single weekend. On those sleepovers we talked very frankly about a lot of topics, including “relationships,” of course, though among us only Hannah Petroski had an actual, long-term boyfriend, Ryan Brown. The two of them were really serious, and had almost had sex.

“We are a

millimeter

away from actually doing it,” Hannah had revealed one weekend. And though I didn’t exactly know what that meant, I nodded and pretended I did. Hannah and Ryan had been in love since Mrs. Delahunt’s kindergarten class. They’d had their first kiss on a carpet remnant in the nap corner.

After I lost Reeve, my friends came around a lot at first, dropping solemnly by the house. I could hear them from my bedroom when they stood in the front hall and talked to my parents. “Hi, Mr. Gallahue,” one of them would say. “Is Jam doing any better? No? Not at all? Wow, I don’t really know what to say. Well, I baked her some snickerdoodles . . .”

But when they knocked on my bedroom door I never wanted to talk to them for very long. “I just wish you’d get over this already,” Hannah finally said one day, sitting on the edge of my bed. “You didn’t even know each other for very long. What was it, a month?”

“Forty-one days,” I corrected.

“Well, I know you’re having a hard time,” she told me. “I mean, Ryan is my life, so it’s not as if I can’t appreciate it in

some

way. But still . . . ,” she added, her voice trailing off.

“But still

what

, Hannah?”

“I don’t know,” she said. Then she added, miserably, “I have to go, Jam.”

If Reeve had been there I would’ve said to him, “Don’t you hate the way people say, ‘But

still,

dot-dot-dot’ and let their voices kind of drop away, like they’ve actually finished the sentence? ‘But still’ doesn’t mean

anything

, right? It just means you can’t explain what you feel.”

“I do hate that,” Reeve would’ve said. “People who say ‘But still’ have

Satan

in them.”

He and I just tended to see the world the same way. After I lost him, I stayed in my room, drowsing on my bed. Once I wore my Tweety Bird nightshirt for five days straight. My friends stopped coming. No more visits, no more snickerdoodles. My parents made me try to go back to school, but everyone there stared at me because they knew how much I’d loved Reeve. I just sat in class with my eyes shut, hardly listening to anything being said.

“Hello in there,” a teacher would say. “Jam,

hello

?”

Sometimes, in the middle of a school day, I’d be standing in a patch of red light under the exit sign by the gym, or sitting on a beanbag chair in a corner of the library. And suddenly I’d remember that this was a place where I’d been with Reeve, and I’d go into a total panic. The breath would fly out of my chest, and I’d run down the hall and out through the fire doors and keep going.

At first, some teacher or staff person would always run after me, but after a while they got tired of running. “I’m too old for this!” the school nurse once bellowed at me from across the playing fields.

“If Jamaica can’t bring herself to stay at school during the day,” the principal said to my parents, “then perhaps you ought to make other arrangements for her.”

So they tried homeschooling. They brought in a former history teacher who, we’d all heard, had been fired for coming to class wasted on vodka shots. He was a nice guy with a sad, creased face like one of those Shar-Pei dogs, and though he was never drunk when he came to tutor me, I just couldn’t pay attention. Again, I drifted off. “Oh, Jam,” he said. “I’m afraid this isn’t working.”

• • •

Now, after my mom and dad and my brother, Leo, have said their good-byes to me in my dorm room—all of them so upset, and me sort of empty and thick inside—and after I’ve sat through baked chicken, green beans, and quinoa in the dining hall, overwhelmed by all the new faces and voices around me, but staying separate and not talking to anyone, and after a night spent barely sleeping, I lie curled in bed on the first morning of classes at The Wooden Barn.

And DJ, already fully dressed and with her hair in my face, demands to see my “skedge.” I motion vaguely toward the desk, where some of my non-clothing belongings are piled in no particular order. DJ paws through them and finally pulls out a folded piece of paper. Her expression changes as she looks at it.

“What?” I ask.

DJ looks at me strangely. She’s half Asian, half Jewish, with straight, shining dark hair, and freckles tossed across her face. “You have Special Topics in English?” she says, her voice rising up in disbelief.

“I don’t know.” I haven’t checked my classes. I really don’t care.

“Yeah, you do,” she says. “It’s your first class of the day. Do you know how unusual it is that you got in?”

“No. Why?”

DJ sits down on the bed at my feet. “First of all, this is a legendary class. The person who teaches it, Mrs. Quenell, only teaches it when she wants to. Like, last year she decided it wasn’t going to be offered at all. She said there wasn’t the right ‘mix’ of students, whatever that means. And even when she does teach it, almost

nobody

gets accepted into the class. You go through this whole effort of applying for it, but basically they always give you another class instead.