Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (33 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

10.75Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The reason why self-control, when considered across the wide spectrum of behavior, benefits society more than individuals comes down to different cost-benefit equations for individuals versus society.

Say you are a smoker and you want to give it up.

Even though

you know in the long run quitting is far better for your health, it is very difficult to succeed in quitting.

Why?

Because the short-term benefits of smoking compete with the long-term benefits of not smoking.

This may sound sacrilegious, but if you are addicted to nicotine, then it is truly in your immediate self-interest to have a cigarette right now because having one feels far better than not having one.

It literally pains the body not to have a cigarette when cravings come on strong.

It is only because you can focus on the long-term benefits of not smoking that you may be able to stave off the urge to smoke.

For the individual, there is a short-term benefit to smoking and a long-term benefit to not smoking, and the individual must wage a battle between the two.

For society, there is no such trade-off.

Society gets almost no short-term benefit from your smoking.

It cannot enjoy the cool flavor, experience the nicotine rush, or feel your nerves calming down.

For society, your smoking is bad from nearly all angles, at all times, and your not smoking is good from almost all angles at all times.

When we think of self-control as willpower, it conjures up visions of the rugged power of the individual overcoming any obstacle.

But when we think of self-control as self-restraint, it leads us to wonder whether the individual is actually the prime beneficiary of those self-control efforts.

Self-control typically pits momentary happiness against an abstract better life in the future.

That abstract better life almost always aligns with society’s goals, but as John Lennon implied, your momentary happiness is not a priority for society.

As we have said from the beginning, we think people are built to maximize their own pleasure and minimize their own pain.

In reality, we are actually built to overcome our own pleasure and increase our own pain in the service of following society’s norms.

Once again, this highlights how poor our theory of “who we are” is.

Yet the first textbook ever written on social psychology, by Floyd Allport, nailed this idea almost a century ago.

Allport argued that

“socialized behavior is thus the supreme achievement

of the cortex… .

It establishes habits of response in the individual for social

as well as for individual ends, inhibiting and modifying primitive self-seeking reflexes into activities which adjust the individual to the social as well as to the non-social environment.”

We discussed in the last chapter how the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) may serve as a Trojan horse for social influence, allowing the beliefs and values of whatever society we mature in to become internalized and treated as personal beliefs and values, without our realizing that this psychological invasion has taken place.

Despite these beliefs and values becoming something we strongly endorse, they sometimes have difficulty competing with our unsocialized urges and impulses.

As comedian Louis C.K.

once said,

“I have a lot of beliefs, and I live by none of them.”

Having the same beliefs as others in our group (for example, classroom, business, society) helps us harmonize—to get along and like one another.

Most of the time we can get by assuring others we share their beliefs and values without having to enact them.

The MPFC may make sure we talk the talk, but some insurance was needed to make sure we walk the walk, and that is where the VLPFC comes in.

If we are sufficiently motivated, the VLPFC can help us to tip the balance so that our thoughts, feelings,

and

behaviors are guided by our socialized beliefs and values over the strong dictates of our presocialized urges and impulses.

Who Controls Our Self-Control?

In the eighteenth century, British philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed something that would lead to

“morals reformed—health preserved—industry invigorated.”

He had designed a new kind of building called a

panopticon

that he believed was the key to making people do the things they should.

Bentham’s plan was to make all of the people in a particular group, whether prisoners, students, employees, or hospital patients, able to be observed at all times long before security cameras would achieve this end.

The plan was to build

rooms around the perimeter of a circle facing in toward the open space in the middle.

In the case of a prison, an individual cell would have solid walls on each of its sides except for the side facing the middle of the circle—that side would have bars keeping the individual in, but it would be open otherwise.

In the middle of the circle, a guard tower would sit with 360-degree views of all of the cells, which could be stacked several floors high.

This would allow a single prison guard, “without so much as a change of posture, [to view] half of the whole number” of prisoners.

The remaining architectural element is what made the panopticon ingenious.

Bentham suggested that, ideally, each prisoner would be watched by a guard at all times because being watched and the threat of punishment would keep prisoners in line.

The central tower would give the greatest viewing span possible, yet still it wasn’t possible to have a single guard or even a few guards truly pay attention to all prisoners at all times.

Bentham’s solution was to ensure that all prisoners felt they

might

be under a watchful eye at any given moment without knowing whether they actually were or were not.

The guard tower was to be built so that guards could see out but prisoners could not see in.

A prisoner might be watched at any time “and not being able to satisfy himself to the contrary, he should

conceive

himself to be so.”

Bentham’s great insight was that being watched by an authority is not the only way to keep people in line.

Rather, it is sufficient for people to know they are

seeable

, that there is the potential for them to be judged, evaluated, and punished.

Being seeable is enough to trigger us to restrain our unsocialized impulses through self-control.

Evolution has wired us with

panoptic self-control

in which the mere possibility of being judged and evaluated by others dramatically increases our tendency to behave in line with society’s values and morals.

This might seem like a strategic, rational thing to do.

If I’m going to steal, I should steal only when I am sure I cannot be caught.

Until then, I should behave publicly like someone who

has no intention of stealing.

But as we will see, research shows that people take this to the extreme, beyond what is rational.

In one study, an experimenter “accidentally” dropped a large stack of papers in front of the participant.

Sometimes there was a visible security camera in the room, and sometimes there wasn’t.

The subject was 30 percent more likely

to assist the experimenter if the security camera was present, indicating the possibility of additional observers.

Another study found that individuals were twice as likely to cheat

on a test in a room that had the lights dimmed, making observation of their immoral behavior more difficult.

In a third study,

subjects wearing eye tracking devices

(that allowed the experimenter to reconstruct where the subjects had been looking) were much less likely to look at a risqué poster on the wall than those not wearing this device.

In each of these cases, the subjects were calibrating their behavior to reality.

The more likely they were to be observed, the more they acted like it.

Panoptic self-control also goes beyond these rational responses to situations in which there is merely an abstract indicator of being seeable, even when we know we are not actually being observed.

Imagine in the break room at work, there is an “honesty box” where you are meant to pay for whatever drink you take from the fridge.

There is a poster on the wall indicating the price of each drink; you are meant to drop that amount in the honesty box.

No one else is in the room with you, and you don’t hear any footsteps coming toward you.

Do you pay for your drink?

If so, how much?

Would it matter if the poster on the wall had some pictures of flowers on it?

How about if the poster had a picture of a pair of eyes on it?

Not real eyes, not a security camera—just a photograph of someone’s eyes, eyes that can in no way actually see what you are doing.

Compared to the flower-adorned poster, the one with the eyes

led people to pay 276 percent more into the honesty box

.

In a public cafeteria,

a similar “eyes poster” nearly halved the amount of littering

that people did.

Even pictures of a defunct toy robot’s eyes

led to larger donations in a laboratory-based economics game.

Finally,

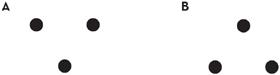

my favorite: a triangle of three dots in the approximate configuration of two eyes and a mouth contrasted with three dots positioned so that the single dot is at the top (see

Figure 9.2

).

Men presented with the “face” version were three times

as likely to donate money to another player in an economics game as men seeing the triangle with the single dot at the top.

Figure 9.2 Dot Configurations That (A) Do and (B) Do Not Induce Prosocial Behavior.

Adapted from Rigdon, M., et al. (2009). Minimal social cues in the dictator game.

Journal of Economic Psychology

, 30(3), 358–367.

It is one thing to strategically take into account whether you are being seen before you engage in bad behavior, but what does a photograph of eyes or dots forming a triangle imply about the actual likelihood of your getting caught and punished?

Rationally, people in these studies can tell you that they know they are not being watched and are not likely to be caught, no matter what they choose to do.

Nevertheless, people restrain themselves

as if

they might be seen.

Panopticons of the Mind

Think back to the days of your youth when October 31 represented the single best opportunity of the year to gorge yourself with so much candy you might actually regret it afterward.

On Halloween, all you have to do is knock on a stranger’s front door in some semblance of a costume, and you are rewarded with candy.

Imagine you walk up to the forty-second front door of the evening, and just after

the owner of the home greets you, he gets an important phone call.

He says, “I’m sorry, but I need to take this call.

The candy bowl is right inside the door.

Go ahead and take one piece of candy.

But I need to go to the other room.”

He walks away and leaves you alone with a large bowl of candy.

What do you do?

Do you take a single piece as he invited you to do, or do you put as much in your bag as you can, as quickly as possible.

No one can see you.

Well, one person can see you—you.

Behind the candy is a mirror that reflects your own actions back to you.

Would this affect your decision?

Apparently, when put in this situation, our natural impulse is to take more than we should.

When children (ages nine and up) were put in this scenario

without a mirror, a little more than half of them took more than the one piece of candy that they had been instructed to take.

But when they could see themselves in the mirror, fewer than 10 percent of the children took more than one piece of candy.

This is staggering.

The mirror made children five times less likely to violate a social norm.

Just seeing one’s own reflection is enough to bring our self-control online to overcome the impulse to snag some extra candy.

A century ago, George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley each suggested that

self-consciousness is essentially a dialogue

between our impulsive self and a simulation of what we imagine people important to us would say to us if they knew what our impulsive self was getting ready to do.

We experience self-consciousness as a private internal process, but according to these psychologists, it is actually a highly social process during which we are reminded of what society expects of us and then we prod ourselves accordingly.

In essence, this view suggests that we are our own panopticon: both seer and seen.

This isn’t just about Halloween trick-or-treatery in young children though.

In a laboratory study,

first-year college students were ten times less likely

to cheat on a test in the presence of a mirror (71 versus 7 percent).

In the absence of any observers, the natural impulse is to cheat (apparently), but people uniformly restrain this

impulse when they see themselves.

People are also more likely to conform

to others in the presence of mirrors across a variety of contexts.

Other species exhibit self-control, and some can even recognize themselves in the mirror, but only humans are built such that seeing themselves, a reminder of their potential visibility to others, is sufficient to trigger self-restraint.

Seeing ourselves as others would see us (that is, our visible appearance) is sufficient to engage our self-control to overcome our unsocialized impulses in order to fall in line with society’s expectations.

When we began our discussion of self-control, it seemed like a mechanism that would primarily support our own individual interests, putting ourselves in control of our lives.

As we have seen, self-control operates at least as often to benefit society.

We are built such that the most trivial reminders of ourselves as social objects keep us in check.

Self-control enhances social connection because it helps us to prioritize the good of the group over our own narrow self-interest.

Self-control increases our value to the social group, and by conforming to group norms, we reinforce the group’s identity as well.

Self-control is a source of social cohesion within the group, putting the group before the individual.

This is the essence of

harmonizing.

Other books

Angel Face by Suzanne Forster

Undenied by Sara Humphreys

Opposing Forces by Anderson, Juliet

The Missing Dog Is Spotted by Jessica Scott Kerrin

Wicked Lies by Lisa Jackson, Nancy Bush

A Summer Shame by West, Elizabeth Ann

Beyond the Shadows by Cassidy Hunter

The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly by Matt McCarthy

Damaged by Kia DuPree

The Whispering Statue by Carolyn Keene