Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (15 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

8.89Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Alexis de Tocqueville, the French scholar who wrote the first great book about the United States,

Democracy in America

, in 1835,

noted his surprise when it came to Americans’ thoughts about their own good deeds:

“The Americans … are fond of explaining almost all the actions

of their lives by the principle of self-interest… .

In this respect I think they frequently fail to do themselves justice; in the United States as well as elsewhere people are sometimes seen to give way to those disinterested [that is, not self-interested] and spontaneous impulses that are natural to man; but the Americans seldom admit that they yield to emotions of this kind.”

The fact is, we are full of both selfish and unselfish motives.

And this is no accident.

Mammalian brains are wired to care for others, and among primates this caring extends to at least some non-kin, even when there is no material return on the investment.

Because of the way our brains are wired, eating a delicious piece of cake is enjoyable whether we are hungry or not.

Similarly, helping others feels good whether we expect something in return or not.

Just imagine what things would look like if we were taught about this in school and we understood that altruistic helping is just as natural as being selfish.

The strange stigma associated with altruistic behavior would be lifted, perhaps engendering far more pro social behavior.

A Lifetime of Pain and Pleasure

In this chapter and the previous one we have looked at two of the major evolutionary motivational tools that work together to ensure that all mammals are concerned with their social world.

Pain and pleasure are the driving forces of our motivational lives

.

The animal kingdom is full of species that successfully avoid threats that may cause harm, and they are drawn to potential rewards that can help them survive and reproduce.

It isn’t surprising that mammals are built to avoid predators or to remember where they found the cheese in the maze last time.

What is surprising is that these basic pain and pleasure motives have been co-opted to serve our social lives as well.

The single most important need of an infant mammal is to be continuously cared for by an adult.

Without this, all other needs of the infant go unmet, and it will die.

Creating ways to keep us connected is therefore the

central problem of mammalian evolution

.

By making threats to our social connection truly painful, our brains produce adaptive responses to these threats (for example, an infant’s crying, which gets a caregiver’s attention).

And by making the care of our children intrinsically rewarding and reinforcing, our brains ensure that we will be there for our children even before we are needed.

Oftentimes there are unintended consequences of evolutionary adaptations.

Did the need to be socially connected and the pleasure we take in caring for others contribute to the evolution of romantic relationships that extend beyond simple procreation?

These pain/pleasure responses may have evolved for the purpose of infant caregiving, yet they stay with us for a lifetime, radically shaping our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors till the end of our days.

The downside to these social motivations is that they can have truly harmful consequences when they go unsatisfied.

The severing of a social bond

—whether it’s the end of a long-term romantic relationship or the death of a loved one—is one of the greatest risk factors for depression and anxiety.

Although adults can survive with unmet social needs far longer than with unmet physical needs, our social bonds are linked to how long we live.

Having a poor social network

is literally as bad for your health as smoking two packs of a cigarettes a day.

The social motivation for connection is present in all of us from infancy.

It is a pressing need, with a capital

N

.

The evolutionary fallout from the presence of these social needs is a major advantage to those who are able to minimize their social pains and maximize their social pleasures.

Building and maintaining social networks is no easy feat.

Just watch any reality show, from

Survivor

to MTV’s

Real World

.

Fortunately, evolution has given us not one but two brain networks that help us to understand those around us and to work more cohesively with them.

Connection is the foundation on which our social lives are founded, but evolution was far from finished, making sure we would make the most of our social lives.

Part Three

Mindreading

M

ost of us believe that a coin flip can resolve nearly any stalemate fast and fairly.

The ancient Romans called this

navia aut caput

, referring to the ship and the head on the two sides of their coins.

Flipping a coin seems like a reasonable way to resolve such standoffs because it appears just as likely to land on heads or tails.

Except that it isn’t.

A few years ago,

a group of medical residents were each asked to flip a coin 300 times

under rigorous testing conditions and to try to make the coin come up heads on each flip.

These were not gamblers or con artists, and they were not given much time to practice.

Nevertheless, each resident was able to flip more heads than tails.

One resident turned more than 200 heads, for a hit rate of 68 percent—far above random chance.

Statisticians from Stanford University analyzed the physics of coin tossing

and determined that without any mischievous intent on the part of the flipper, a fair coin will tend to land facing the same way it started.

The same-side advantage is small (51 to 49 percent); but if true, who would ever agree to a coin toss again?

When San Francisco 49er Joe Nedney heard about the coin flipping results, he suggested a switch to rock-paper-scissors to decide which NFL team would kick off or receive the ball each game.

How many children have been doomed to retrieve the ball from the scary neighbor’s yard by a lost round of rock-paper-scissors?

If coin tossing is out and rock-paper-scissors is the fair way to break a deadlock, then Bob Cooper must be the luckiest guy on the planet.

In 2006, he defeated 496 contestants to claim the title of Rock-Paper-Scissors World Champion.

As most people know, the game is simple.

Two players simultaneously reveal a hand gesture indicating rock, paper, or scissors.

Rock crushes scissors.

Scissors cut paper.

Paper covers rock.

Players have three options, and each option can beat one other and is beat by one other (if both players select the same gesture, it’s a tie, and they go again).

In the final match of the Rock-Paper-Scissors World Championship, Cooper, a sales manager from London, went up 5 to 2 by throwing rock to his opponent’s scissors.

He needed one more for the win.

In the next round they both threw paper.

Then rock.

Then scissors.

Three tie rounds in a row.

Finally, in the fifteenth round of their match, Cooper threw scissors over paper and was crowned the king of rock-paper-scissors.

The match can be viewed on YouTube, and the first comment appearing below the video goes for the high sarcasm of “I can’t wait to see the coin flip championships.”

To the uninitiated, rock-paper-scissors seems random, with each party having an equal chance of winning.

If you believe that, I know some rock-paper-scissors experts who would love to schedule a high-stakes match with you.

The best of the best are mindreaders; they know what you will play before you do.

Novices have clear tendencies that can be exploited by opponents.

For instance, men who are new to rock-paper-scissors tend to start matches by throwing rock more often than paper or scissors, possibly because rocks are associated with strength.

Another tendency is to change gestures after the same one has been thrown two rounds in a row.

Players with more experience can counter these novice moves, dramatically increasing their likelihood of winning.

Of course, in competition play there are no novices.

Experienced players carry out a series of complicated attacks and counterattacks.

After being crowned world champion, Bob Cooper told a reporter that the essence of rock-paper-scissors is about

“predicting what your opponent predicts you’ll throw.”

It’s about getting inside your

opponent’s head and manipulating what he believes you will throw and understanding how he will use that information to counter you, so that you can in turn throw a gesture that will counter him.

It’s all about mindreading.

Marcus du Sautoy, a professor of mathematics at Oxford University, tried the one strategy that does not depend on mindreading and would seem invincible to the mindreading efforts of others.

He decided each throw entirely randomly, using successive digits in the number pi (3.1459 … ) to determine his next throw.

By not strategizing at all from round to round, he took away his opponents’ ability to manipulate him.

But although he had some luck with his “can’t lose, can’t win” strategy, he was no match for Bob Cooper.

Cooper beat him eight straight times.

Rather than relying on statistical knowledge, Cooper was probably detecting subtle facial expressions and body language that gave away du Sautoy’s next move.

More mindreading.

Everyday Mindreading

Franz Brentano is a little-known German philosopher who is the forefather of some of the most important philosophers and psychologists of the twentieth century.

He trained Edmund Husserl, who later trained Martin Heidegger, one of the giants of modern phenomenological and existential philosophy.

He also trained Carl Stumpf, who trained the first Gestalt psychologists (“the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”), and Kurt Lewin, who is considered one of the founders of social psychology in the United States (having left Germany at the start of World War II).

In 1874, Brentano published a long forgotten text,

Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint

, that along with Wilhelm Wundt’s enormously influential

Principles of Physiological Psychology

, published in the same year, were

the first modern texts on psychology

.

Brentano argued that the central fact of human psychology is

that our thoughts are “Intentional.”

Brentano’s meaning is derived from Aristotle and twelfth-century scholastic philosophers who had discussed the “intentional inexistence” of objects.

Essentially,

Intentionality

refers to the fact that we have thoughts, beliefs, goals, desires, and intentions about other things.

Our thoughts can be about objects in the world or about imaginary entities like wizards at Hogwarts, or even about other thoughts, but thoughts always extend beyond themselves to refer to something else.

Nothing else in the known universe has this intrinsic characteristic of “aboutness” (for example, rocks aren’t “about” anything; they just are).

It took another half-century after Brentano before the corresponding central fact about our social minds was identified: we possess the capacity or, more accurately, the inescapable inclination to see and understand others in terms of their Intentional mental processes.

When we see others, we want to know what they are thinking about and how they are thinking about it.

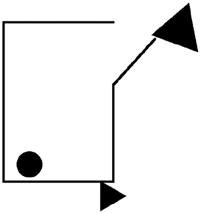

To first demonstrate this penchant for everyday mindreading

, Fritz Heider showed people a short animation of two triangles and a circle moving around, and then he asked people what they saw (see

Figure 5.1

).

Here’s what people didn’t see: two triangles and a circle moving around.

Instead, people saw drama.

“The big triangle is a bully that is picking on the small triangle and circle, who are running scared but then figure out how to trick the big triangle and escape.”

Or

“The big triangle is a jealous boyfriend of the female circle, and he is angry because he caught the circle flirting with the small triangle.”

Everyone saw thoughts, feelings, and intentions in these shapes that clearly had none—shapes don’t have minds!

We see thinking, feeling minds everywhere around us: we treat our computers, cars, and even the weather as if they have minds of their own.

This overgeneralized tendency to see minds behind events in the physical world presumably evolved to make sure we do not accidentally overlook the actual minds of other people.

Actual minds are hidden, after all.

It would be awfully easy to miss them if we weren’t built to notice them.

Figure 5.1 Heider and Simmel’s Fighting Triangles.

Adapted from Heider, F., & Simmel, M.

(1944).

An experimental study of apparent behavior.

American Journal of Psychology

, 57, 243–259.

In 1971, a century after Brentano’s pronouncement, the philosopher Daniel Dennett codified

our tendency to see others in terms of minds guiding behavior

.

Dennett suggested that regardless of whether we were justified in assuming that other minds exist, we are built to assume that others are Intentional creatures.

Dennett referred to this as taking the

Intentional stance.

It is because our own minds think about the minds of others (who in turn think about us) that we can have the high comedy of Daffy Duck’s “I know that you know that I know” standoffs with Bugs Bunny.

While Bugs and Daffy might be overdoing it, this kind of interaction is one of the primary reasons why societies are able to work cooperatively to build soccer leagues, schools, and skyscrapers.

Other books

War by Shannon Dianne

Wrapped in You by Kate Perry

She Writes Love... by Sandi Lynn

Second Chances (The Extinct Race Series) by Michelle Farrell

Saving Sara (Masters of the Castle) by Smith, Maren

The Innocent by Evelyn Piper

Christmas in Apple Ridge by Cindy Woodsmall

She Will Build Him a City by Raj Kamal Jha

PET by Jasmine Starr

Hunter (Campus Kings): A Football Secret Baby Novel by Celia Loren