Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (11 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

9.89Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

CHAPTER 4

Fairness Tastes like Chocolate

I

magine you work for the law firm of Horn, Kaplan & Goldberg, and you are up for early promotion to partner.

The promotion is likely to go to you or to Steve, a lawyer down the hall.

You’ve got the numbers on your side.

Your performance reviews have been stronger for six straight quarters, you have a better record in the courtroom, and over the past three years you have billed 30 percent more hours for the firm than he has.

Steve has one thing going for him, an ace in the hole.

He’s Steve Goldberg, nephew of one of the senior partners in the firm.

Steve’s a good lawyer, and he deserves to make partner too, but you deserve it more.

If there is only one slot, by all rights, it should be yours.

Not getting the position would mean missing out on a higher salary, but the social implications would make this outcome painful as well.

Being passed over would hurt because it would feel like the firm’s partners were rejecting you.

Furthermore, this outcome would clearly constitute a social insult that everyone in the firm would know about.

In this case, both your so-called basic needs and social needs would take a hit.

As it turns out, fortune shines down on you, and the keys to the executive washroom are handed to you instead of Steve Goldberg.

The promotion comes with a large raise, and you and your husband will now have the money to move up to your dream home in the neighboring town with better schools for your children.

No matter

what your profession or professional aspirations, you have probably imagined or had this kind of moment.

Likely to be lost in your celebration over your newfound wealth and status is the role fairness might have played in your positive feelings after learning the outcome.

The partners could have prioritized Steve’s bloodline over your hard work and productivity.

Even three-year-olds sharing cookies become upset when they are treated unfairly.

Unfair treatment is demoralizing and often leads to a host of negative feelings.

But does fair treatment produce positive feelings of its own?

Fairness seems a bit like air—its absence is a lot more noticeable than its presence.

Being treated fairly is usually confounded with obtaining the better outcome, so it’s hard to parse our positive feelings for each.

If you are walking with a friend, and he picks up a $10 bill that you both saw lying on the ground and offers to share it with you, the bigger the cut he offers to you, the fairer it is.

So when he gives you $5, how much of your happiness is due to getting $5 instead of $3 or $0 and how much is due to feeling valued by your friend?

There have been a couple approaches to separating the joy of receiving more good stuff from the joy of being treated fairly.

One approach has involved measuring the perceived fairness of events and the material benefit that people receive, separately.

This has allowed researchers to use statistical analysis to see how both of these factors relate to people’s feelings about the events.

In one study, participants were put on a team

and independently performed an anagram

task (for example, figuring out that LIOSAC can spell SOCIAL).

The team was then paid based on their overall group performance.

After receiving the money, the team members had to negotiate among themselves how to split their earnings.

This was where things got tricky because some team members invariably scored higher than others and thus were more responsible for the payout the team received.

Some team members found an equal distribution to be fair (“We all got the same amount”), and others found an equitable distribution to be fair (“We received according

to our scores”).

But whether the team members received a lot or a little, as long as they believed the process was fair, they had more positive emotions.

This same pattern has been observed in field research as well.

Psychologist Tom Tyler found that defendants in court cases

were happier with their courtroom experience if they believed they were treated fairly, even when the verdict did not go their way.

How do we know these people really mean what they say?

Maybe they don’t really know how they feel, or maybe they are trying to give experimenters the answer they are looking for.

Golnaz Tabibnia and I thought that by scanning the brain, we would be able to garner additional

evidence for or against the notion that fairness

is intrinsically rewarding to us.

We asked individuals lying in an MRI scanner to play an economic bargaining game that exposed them to both fair and unfair outcomes.

They played a variant of the Ultimatum Game, in which two players have to agree how to split some amount of money, say, $10.

One player, called the

proposer

, makes a recommendation about how much each of them should get, and the other player, called the

responder

, then decides whether to accept the offer.

If the responder accepts, then both individuals get the amount suggested by the proposer.

But if the responder rejects the offer, both players get nothing.

A proposer might suggest that he get $9 and the responder get $1.

And if you guessed that responders might be insulted by this kind of offer, you would be right.

Responders commonly reject highly unfair offers, preferring to get nothing at all rather than let this insult go unpunished.

This seems to fly in the face of rational self-interest, but it’s what people do.

In our study, participants played the part of the responders and saw a series of offers from different proposers.

We wanted to see if the brains of our participants would respond differently to fair and unfair offers.

We faced the same challenge that we saw in our law firm example at the beginning of this chapter.

An offer of $5 out of $10 is more fair than an offer of $1 out of $10, but the $5 offer is

also much more lucrative.

To deal with this complication, we varied the total amount to be split from offer to offer: responders would see offers of $5 out of $10, as well as offers like $5 out of $25.

In both cases, the material amount of the offer was equivalent ($5), but the offers differed significantly in their fairness.

By doing this, we could attribute neural differences to the effects of fairness rather than to the financial gain.

Most studies have used this paradigm to look at neural responses to unfair offers.

Consistent with the social pain findings described in

Chapter 3

, these

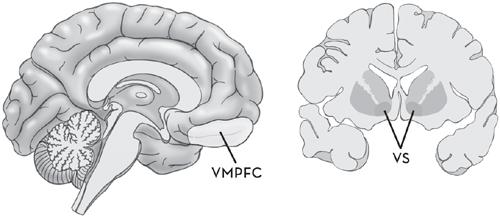

studies typically observe activity in the anterior insula and the dACC

.

However, when we looked at which regions were more active during fair offers as opposed to unfair offers, almost all of the regions we observed were part of the brain’s reward network (see

Figure 4.1

).

Being treated fairly turned on the brain’s reward machinery regardless of whether it led to a little money or a lot.

An even more dramatic demonstration followed when

a group of researchers from Cal Tech examined the neural responses

of individuals as their own potential winnings were given to another participant.

Ordinarily, this experience would be painful rather than pleasurable.

Who wants to see one’s own money taken away?

As it happened, the individuals who won a $50 lottery at the beginning of the study and then saw the other participant not win any money showed robust activity in the brain’s reward system when the lottery loser went on to win money on subsequent trials—even though it was at the participant’s own expense.

Subsequent wins by the lottery losers brought the losers’ total earnings more in line with the participants’ own earnings, and seeing a fair distribution of the winnings was more rewarding to participants than gaining more for themselves.

In other words, fairness trumped selfishness.

Fairness is one of many cues that we have that we are socially connected.

Fair treatment implies that others value us and that when there are resources to be shared in the future, we are likely to get our fair share.

Fairness is clearly a more abstract sign of social

connection than many others we could imagine, and it’s important enough that our brain’s reward system is sensitive to it.

The same brain regions that are associated with loving the taste of chocolate or any other physical pleasures respond to being treated fairly as well.

In a sense, then, fairness tastes like chocolate.

This chapter isn’t about fairness per se, but rather about the various social signs, events, and behaviors that reinforce our connection to an individual or the group.

Because these tend to activate the brain’s reward system,

they are referred to as

social rewards.

Just as social and physical pain share common neurocognitive processes, so to do physical and social rewards share common neurocognitive processes.

Figure 4.1 The Brain’s Reward Circuitry (VMPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex; VS = ventral striatum)

Oscar and Sally

In the 1984 film

Places in the Heart

, actress Sally Field portrayed a 1930s southern widow trying to keep her farm out of foreclosure.

For her performance, she went on to win the Academy Award for best actress.

Her acceptance speech was memorable for its enthusiastic earnestness.

In the most famous line from Field’s acceptance speech, she declared, “You like me.

You really like me.”

Even if you didn’t know who said it, I bet you have heard that line before and

know it was uttered with a strong emphasis on the word

really

.

It exemplifies the adulation that actors crave.

There are two errors in the previous paragraph, one more important than the other.

The minor error: Sally Field did not actually say this line in her acceptance speech.

The real line in her speech was, “I can’t deny the fact that you like me, right now, you like me.”

We probably misremember the quote because of the other, more important error.

It isn’t just actors who are motivated by being liked—we all are.

The misquote is so sticky because it exemplifies a central human need.

We all have a need to belong.

Signs that others like, admire, and love us

are central to our well-being.

Until very recently, we had no idea how the brain responds to these signs.

Recent neuroimaging has changed that.

While lying inside the bore of an MRI scanner, perhaps the most dramatic positive sign that we can get from another person, short of a marriage proposal, is to read something that person has written to express their deep affection for us.

In a recent study, Tristen Inagaki and Naomi Eisenberger

asked participants for permission to contact their friends

, family, and significant others.

Tristen wrote to the important people in a participant’s life and asked them to compose two letters: one that contained unemotional statements of fact (for example, “You have brown hair”) and one that expressed their positive emotional feelings for the participant (for example, “You are the only person who has ever cared for me more than for yourself”).

Subjects would then lie in the scanner while reading these letters written about them by several of the people they care about most.

Our intuitive theories suggest there is something radically different about the kind of pleasure that comes from people saying nice things about us and the kind of pleasure that comes from eating a scoop of our favorite ice cream.

The former is intangible, both literally and figuratively, while the latter floods our senses.

Although there are surely differences between physical and verbal sweets, this fMRI study suggested that the brain’s reward system seems to treat

these experiences more similarly than we might expect.

Being the object of such touching statements activates the ventral striatum in the same way that the other basic rewards in life do.

In a follow-up study, Elizabeth Castle and I

looked at how rewarding these touching statements really were

.

We asked a group of individuals to bid money to try to win these statements.

In the end, a large proportion of the participants were willing to give back their entire payment for the study, just to get to see these special words.

We may give lip service to the power of money, but the power of knowing we are loved can be just as potent.

It is easy to imagine

our reactions to getting this rarely shared positive feedback

from the people who matter most to us, but would social feedback from complete strangers have the same effect?

Surprisingly, yes.

Imagine Penelope, a twelve-year-old, lying in a scanner watching as a series of faces of other kids appears on the screen.

Penelope has never met any of the people she is seeing, but she is informed after seeing each face whether that person wanted to have an online chat with her.

Participants like Penelope showed increased activity in the brain’s reward system when finding out that those strangers wanted to have an online chat with them.

These findings were remarkable for two reasons.

First, the feedback was ostensibly from complete strangers who had seen the participant’s picture and knew very little else about him or her.

Second, the positive feedback led to reward activity even when the participants had no interest in having a chat with the other person.

So even strangers we don’t want to interact with activate the brain’s reward system when they tell us they like us.

Other books

Saving Sam (The Wounded Warriors Book 1) by Beaudelaire, Simone, Northup, J.M.

Miss Timmins' School for Girls by Nayana Currimbhoy

Sorry I Peed on You (and Other Heartwarming Letters to Mommy) by Jeremy Greenberg

It's Only a Movie: Alfred Hitchcock by Charlotte Chandler

Harry Kaplan's Adventures Underground by Steve Stern

Sex & Violence by Carrie Mesrobian

Nebula Awards Showcase 2010 by Bill Fawcett

Brie Visits Master's Italy (After Graduation, #7) by Red Phoenix

Everything She Ever Wanted by Ann Rule

Vegan for Life by Jack Norris, Virginia Messina