Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (27 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

14Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Bill Kelley, Todd Heatherton, and Neil Macrae, prominent social neuroscientists

from Dartmouth College, ran a simple but elegant experiment that answered this question conclusively.

In an fMRI study, participants were shown adjectives, such as

polite

and

talkative

.

For some of the trials, participants had to judge whether the adjective described George W.

Bush, who was the U.S.

president

at the time.

On other trials, participants had to judge whether the adjectives described themselves.

The critical analysis examined whether there were any regions of the brain that were more active when people judged the applicability of an adjective to themselves as opposed to George Bush.

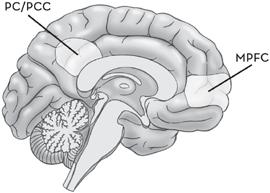

There were only two regions of the brain whose activity followed this pattern.

Just as in the mirror self-recognition studies, there was activity in the prefrontal cortex and parietal cortex.

But unlike the mirror self-recognition studies, these activations were present in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and the

precuneus

—on the midline of the brain where the two hemispheres meet, rather than on the lateral surface of the brain near the skull (see

Figure 8.2

).

In other words, recognizing yourself in the mirror and thinking about yourself conceptually rely on very different neural circuits.

Seeing yourself and knowing yourself are two different things.

There are at least two major implications of this distinction between self-seeing and self-knowing.

Figure 8.2 Brain Regions Associated with Conceptual Self-Awareness (MPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; PC/PCC = precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex)

First, this distinction clarifies what the mirror self-recognition test tells us about the animals that can pass it.

Chimps, dolphins, and elephants all have some sense of their corporeal identity, that

the body they see in the mirror is their body.

However, the fMRI data suggests that passing this test does not imply that these animals engage in self-reflection the same way that we do, reflecting on whether we possess a particular personality trait or wondering what will become of us in ten years.

It does not imply that these animals reflect on the wisdom of their past decisions.

And it certainly does not imply that these animals come to have a conceptual sense of self through introspective contemplation.

Second, the neural separation of representing our own bodies and representing our own minds explains why we can’t get away from Descartes’ mind-body dualism.

All signs point toward mind-body dualism being a bad explanation of what we are, and yet most of us operate like card-carrying dualists.

We can’t help it because it is literally wired into our operating system to see the world in terms of minds and bodies that are separated from one another.

We have one system for thinking about our own minds and another one for recognizing our own bodies, and these systems are separated in the brain.

It is not that minds and bodies are separate realms in reality, but the ways we register them are separated in our brains, and there isn’t much we can do to bridge this neural chasm.

Just as colors and numbers are experienced as radically different because they depend on dissociated systems in the brain, our mind and body are forever cleaved from one another.

The Third “I”

The medial prefrontal region that was observed

in Bill Kelley’s study has appeared again and again in countless studies of self-reflection.

These studies demonstrate that our conceptual sense of self is strongly tied to the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC).

In one review that I published,

the MPFC was observed in 94 percent

of all studies of self-reflection, and it is the only region that is so reliably associated with thinking about “who we are.”

Given that we may be the only species able to think about ourselves conceptually, is there something special about the MPFC that allows us to do this?

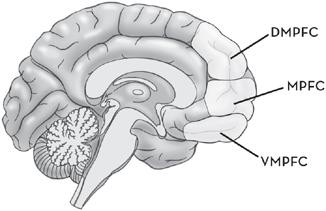

Let’s start with a little anatomy to clarify the region we are discussing.

German anatomist Korbinian Brodmann examined the cytoarchitectonic structure of cells throughout the human brain near the turn of the twentieth century.

He identified about fifty different regions of the cortex, and each has been identified as a

Brodmann area

, a taxonomy that still stands a century later.

The medial wall of the prefrontal cortex can be divided into three regions (see

Figure 8.3

).

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), discussed earlier in the context of reward, is identified as Brodmann area 11.

The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), the central node in the mentalizing system, consists of Brodmann areas 8 and 9.

The medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), identified as Brodmann area 10 (that is, BA10), is sandwiched between the ventromedial and dorsomedial prefrontal cortices.

When you point to your “third eye” on your forehead (whether you do so ironically or not), you are probably pointing at this MPFC region, which is responsible for your sense of having an “I.”

Although there are ongoing debates about the extent to which rodents have something like a prefrontal cortex at all, it is clear that they have no equivalent of BA10;

only our closer primate relatives

(that is, monkeys and great apes) possess this region at all.

Figure 8.3 Different Regions of the Medial Wall of the Prefrontal Cortex (DMPFC = dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; MPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; VMPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex)

Neuroanatomist Katarina Semendeferi examined the size of BA10

across six of the primate species, including humans, that have it.

The size of this region was below 3,000 cubic millimeters in chimps, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons; it was above 14,000 cubic millimeters in humans.

As we saw earlier, raw size comparisons aren’t terribly meaningful because the human brain is so much larger in general.

What is more informative, then, is the percentage of the total brain devoted to BA10.

In nonhuman primates, BA10 takes up between 0.2 and 0.7 percent of the total brain volume.

In humans it takes up 1.2 percent of the total brain volume.

Put another way, BA10 takes up twice as much space in the human brain as it does in the chimpanzee’s brain.

BA10 is one of the only regions of the brain known to be disproportionately larger in humans than in other primates.

Semendeferi also discovered that

BA10 is less densely populated with neurons

than other cortical regions.

Reduced crowding gives each BA10 neuron space to connect to a greater number of other neurons.

The MPFC is clearly pretty special, distinguishing us from other primates.

Given that humans are the only species that we know for sure have a conceptual sense of self, it makes sense that this capacity would be linked to a brain region that is distinctive in humans.

So what does this region do for us?

We in the West spend a lot of time thinking about ourselves.

Some would go so far as to say we are obsessed with ourselves.

We believe that the self that we introspect on is composed of our private stock of personal beliefs, goals, and values.

It holds our hopes and dreams that no one has access to but us.

Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu captured the idea of the self as a source of truth more than 2,000 years ago, writing, “At the center of your being you have the answer; you know who you are and you know what you want.”

Nobel Laureate Herman Hesse highlights the distinctiveness of each self from the others, arguing that

each “represents the unique, the very special

and always significant and remarkable point at which the world’s phenomena intersect, only once in this

way, and never again.”

If the self represents our unique nature, then the MPFC appears to be the royal road to knowing our own hidden truths and the best route to securing personal happiness.

But as we have seen, things are not always as they first appear.

Trojan Man

The myths of Virgil and Homer tell us that Helen of Troy was taken from Greece by a Trojan named Paris in the thirteenth century BC.

Agamemnon, Helen’s brother-in-law and Greek royalty, led a siege against Troy that lasted a decade.

The Trojans withstood the frontal assaults, never allowing the Greeks to breech the city limits.

The Greeks finally turned the tide with the well-known stratagem of the Trojan horse.

The Greeks staged a hasty retreat, leaving behind a giant wooden horse, which the Trojans wheeled into the city as a trophy of their victory.

Unbeknownst to the Trojans, there were Greek soldiers hiding inside the horse, silently waiting for nightfall.

After dark, these warriors exited the horse, took the Trojans by surprise, and opened the gates to the Greek army, resulting in a speedy end to a long war.

Why this digression into Greek history?

The Trojan horse was not at all what it seemed.

Instead of being the spoils of war, it was a cleverly disguised deception that allowed the Greeks entry into Troy and led to its being overtaken by the Greeks.

In the same vein, I would argue that we can describe our sense of self as a

Trojan horse self

.

In the West, we like to think of the self as that which makes us special, providing us with a unique destiny to reach our personal goals and achieve self-fulfillment.

We imagine the self—our sense of who we are—to be a hermetically sealed treasure chest, an impenetrable fortress, that only we have access to.

If this were really the whole story, such a discussion of the self wouldn’t have a place in a book on the social brain.

But as it turns out, the self may be evolution’s sneakiest ploy to ensure the success of group living.

I

believe the self is, at least in part, a cleverly disguised deception that allows the social world in and allows us to be “overtaken” by the social world without our even noticing.

Nineteenth-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche gave the most cynical view of this Trojan horse self, writing:

Whatever they may think and say about their “egoism,” the great majority nonetheless do nothing for their ego their whole life long: what they do is done for the phantom of their ego which has formed itself in the heads of those around them and has been communicated to them.

Nietzsche believed that our sense of self was not something inherently internal to us, a true core to our being, that we gained greater access to over the course of our lives.

Instead, he argued that our sense of self is typically something constructed, primarily by the people in our lives, and that the self is actually a secret agent working for them more than for us.

If one believes that the purpose of the self is to help each of us of maximize personal rewards and achievement by better knowing who we are, then it would be tragic to discover that our self actually does something very different from what we think it does.

Our responses to cultural trends give us some insight into how this process works.

When I see a new look in clothes, my first reaction is often “that looks ridiculous,” yet a few months later I find that the trend looks and feels “right” to me.

For a dramatic example of this, consider baby colors.

Go to any store that sells baby supplies, and you will see a wide array of clothes and equipment in blue or pink, for boys and girls, respectively.

At one level, I don’t like that boys and girls are already separated this way from birth.

At another level, I get it.

Blue for boys and pink for girls just feels right.

It may not be PC, but it’s right—I can feel it in my gut.

Just imagine if some store tried to switch things up and sell pink for boys and blue for girls.

That would never catch on, right?

Actually, it already did.

A hundred years ago, the color scheme for babies was the opposite of what it is now.

Consider this comment from a trade journal published in 1918:

The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls

.

The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.

Other books

Queen of Mars - Book III in the Masters of Mars Trilogy by Al Sarrantonio

Collected Stories by Gabriel García Márquez, Gregory Rabassa, J.S. Bernstein

In Memory by CJ Lyons

Dating A Cougar by Donna McDonald

Muchacho by Louanne Johnson

Todos los niños pueden ser Einstein by Fernando Alberca

Rake's Guide to Pleasure. by Victoria Dahl

Until It's You by Salem, C.B.

Nine Lives by Erin Lee

Keeping Dallas by Amber Kell