Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (24 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

13.48Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Baron-Cohen and his colleagues tested three groups of people on the Sally-Anne task: children with autism (eleven-year-olds), children with Down’s syndrome (ten- to eleven-year-olds), and normally developing children (four- to five-year-olds).

Developmental psychologists measure something called

mental age

, which is a way of equating children of different actual ages based on their overall

mental ability.

The children with autism had the mental age of five-year-olds, hence the much younger age of the normally developing children in the study.

As in previous studies, the normally developing five-year-olds did very well on the Sally-Anne test, with 85 percent of the children getting the right answer.

In contrast, only 20 percent of the children with autism passed the test—a radical departure from the results for the normally developing children.

Perhaps the performance of the children with autism suffered because of the general cognitive difficulty of the task?

If this had been the case, the children with Down’s syndrome should have performed poorly as well, but they actually passed at the same rate as the normally developing children.

Moreover, the children in all three groups showed a similar ability to recall the facts of what happened during the Sally-Anne task, so it wasn’t the case that children with autism weren’t able to keep track of the facts.

These results point to a relatively specific deficit in the mentalizing ability of children with autism.

Subsequent studies have demonstrated other mentalizing deficits

in this group, including the inability to make sense of bluffing, irony, sarcasm, and faux pas.

Autistic individuals are also much less likely to describe

the Heider and Simmel’s Fighting Triangles animations described in

Chapter 5

(see

Figure 5.1

) in terms of mental state characteristics such as beliefs, emotions, and personalities.

Ami Klin, a Yale psychologist, reported normally developing and autistic individuals’ descriptions of the animations, providing a more concrete sense of their Theory of Mind deficit.

First we have a normally developing child’s description:

What happened was that the larger triangle—which was like a bigger kid or a bully—and he had isolated himself from everything else until two new kids come along and the little one was a bit more shy, scared, and the smaller triangle more like stood up for himself and protected the little one.

The big triangle got jealous of them, came out, and started to pick on the smaller

triangle.

The little triangle got upset and said like “What’s up?”

“Why are you doing this?”

When you read that description, it is easy to envision social events taking place and how each of the participants in the drama felt.

The description is full of mental state language and thus gives the inside story of the minds of the animated shapes.

It is natural to describe the scene this way and equally natural to hear someone else describe it this way.

In contrast, here is a description from a child with autism:

The big triangle went into the rectangle.

There were a small triangle and a circle.

The big triangle went out.

The shapes bounce off each other.

The small circle went inside the rectangle.

The big triangle was in the box with the circle.

The small triangle and the circle went around each other a few times.

They were kind of oscillating around each other, maybe because of a magnetic field.

After that, they go off the screen.

If you read only the second story, you will have no sense of the unfolding of any drama.

The child with autism describes shapes moving around with no real meaning, social or otherwise.

It’s important to note that, strictly speaking, this description is far more accurate than the normally developing child’s.

The large triangle isn’t a bully and isn’t jealous.

The small circle isn’t shy and scared.

They are cut-out shapes with no thoughts, feelings, or personalities.

Although the description from the child with autism is more accurate, it is far less

useful

.

It doesn’t give us the kind of insight we all crave into the psychological drama that unfolded, and it doesn’t allow us or the autistic child to predict what might happen next (lawsuits?

tire slashings?

tearful reunion show?).

Not being able to see the world in terms of mental states is a profound disadvantage when everyone else does this naturally.

Not only do autistic individuals not see these movements in psychological terms but this

also limits their ability to connect and share with others who see these events in a radically different light than those with autism.

The Whole Story?

There is little debate among scientists over whether autism is associated with impaired Theory of Mind abilities.

It is.

What is debated is, first, whether this impairment is the primary explanation of the real-world symptoms associated with autism and, second, whether autism is caused by Theory of Mind deficits or whether these deficits are the end result of some other developmental process that is not intrinsically tied to Theory of Mind.

In other words, is the Theory of Mind deficit a cause or a consequence of autism?

As parsimonious as the Theory of Mind account of autism sounds, few studies have linked Theory of Mind ability to real-world problems in autism outside the lab, and there is increasing evidence that Theory of Mind deficits are not the whole story of autism.

There are a couple different reasons for this.

Recall that only 20 percent of the children with autism passed the Sally-Anne test.

That same fact can be stated in a different way: at least some children can pass this test while still qualifying for the diagnosis of autism.

If Theory of Mind were the whole story, then anyone with autism should show a corresponding deficit in Theory of Mind.

The Sally-Anne test isn’t the only or the hardest test of Theory of Mind

, but a subset of autistic individuals with real-world social deficits continue to pass harder Theory of Mind tests, confirming that a person can have autism and yet not have a Theory of Mind deficit.

A second issue is that autistic individuals have other perceptual and cognitive aberrations that bear little relation to the Theory of Mind deficits.

Uta Frith gave a group of autistic children

and a group of normally developing children an embedded-figures test.

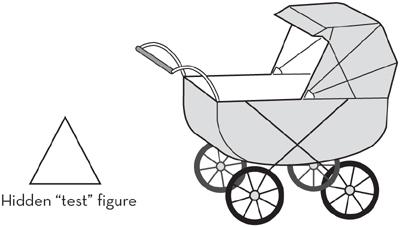

One example is given in

Figure 7.2

.

The children were asked to find where in the picture the “hidden” triangle to the left of the baby carriage

was present (in the same size, shape, and orientation).

I’m guessing you went ahead and did this for yourself and found that it took a little while (hint: it’s in the hood that shades the baby).

Well, it would take you

less

time if you had autism.

Individuals with autism consistently do

better

on this kind of task than other individuals.

Improved performance is typically not described as an impairment, but in this case it reflects a kind of cognitive-perceptual imbalance.

Figure 7.2 An Example from an Embedded-Figures Test.

The exact same triangle (size, shape, and orientation) must be found within the baby stroller.

Adapted from Shah, A., & Frith, U.

(1983).

An islet of ability in autistic children.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

, 24(4), 613–620.

The reason why the rest of us are slower at this kind of task is that our minds are designed to focus on the overall Gestalt meaning of what we see, rather than on the details that must be integrated to give rise to that high-level meaning.

We see lawns, not blades of grass.

Our response to the embedded-figures test depends on our ability to detach from the overall meaning of a picture to search for nonfunctional elements within it.

Autism is associated with a deficit in focusing on high-level meaning

both in seen objects and in language, and thus if a task requires a focus on detail at the expense of the whole, individuals with autism often excel, outperforming others.

There is certainly a parallel between extracting the high-level meaning of seen objects and inferring the goals and motives behind another person’s behavior.

However,

the two deficits do not always go hand in hand in autism

,

and determining why someone acted a certain way versus why a physical event took place does not rely on the same neural circuits, so these do seem to be distinct processes.

One could still argue that a Theory of Mind deficit is the primary explanation of the social impairments in autism and that Gestalt processing deficits might account for other nonsocial impairments.

For this to be true, we would have to assume that training autistic individuals to mentalize better would then lead to corresponding reductions in their social impairments.

Multiple studies have shown that training can lead to sizable gains

in the mentalizing of individuals with autism, and yet, sadly, those gains produce no real-world improvement in social skills.

Cause or Consequence?

The preceding findings point to clear Theory of Mind deficits in autistic individuals but also suggest that they may not be driving the social impairments seen in autism.

This would make more sense if it turned out that Theory of Mind deficits were a secondary consequence of the core deficits in autism, rather than the causal feature intrinsic to autism.

To illustrate this difference, imagine a runner who hurts her left knee while training for a race.

The odds are quite high that within a week she will also have pain in her right hip.

Pain in her left knee will cause her to limp and favor the right leg.

This puts undue pressure on those joints and will often cause pain in the right hip opposite to the injured knee.

In this case, the knee pain is intrinsic to the original injury, but the hip pain is secondary, acquired because of how the body compensated for the knee pain.

As basic as Theory of Mind is to our adult nature, our acquisition of this ability depends in part on having the right kinds of experiences when we are young.

Seeing and hearing other people interact with the world using their mentalizing ability helps to

develop our own ability.

We know this because children who are born deaf

perform just as poorly as children with autism on Theory of Mind tests.

The deaf children do not have any mental deficits and are not socially avoidant, but they cannot hear people speaking and thus are exposed to a socially impoverished environment in which conversations about or invoking mental state language are missed.

Is it possible that something related has occurred in autism?

There is substantial data to suggest that the social deficits in autism precede even the earliest age at which children show evidence of Theory of Mind, so perhaps those earlier changes alter the inputs that autistic children are exposed to.

Autism has historically been diagnosed at the age of three or later.

Thanks to the analysis of home movies, we now have a good idea of what these children look like prior to their diagnosis, in the first and second years of life.

Using careful systematic coding protocols, scientists can identify differences in children destined to become autistic relative to other children who were not so fated.

Children under the age of one already show evidence of poor social interaction and a lack of appropriate social reactions to others.

During the second year, these children tend to ignore others

, prefer to be alone, and continue to demonstrate poor social skills.

If these children are showing a preference for social isolation, it is possible that they, like deaf children, are not getting the social inputs they need in order to develop a mature ability to mentalize on the same developmental schedule as other children.

If so, then we would want to look to neural systems that mature much earlier than the mentalizing system.

The Broken Mirror Hypothesis

The mirror system is evolutionarily more primitive than the mentalizing system, given monkeys have mirror neurons but not Theory of Mind.

The mirror system is thought to be operational in

week-old infants, who show evidence of imitating.

If we are looking for a deficit that precedes Theory of Mind deficits and might even lead to them, the mirror system might just fit the bill.

The first hint that mirror neurons might be central to autism was the well-documented problem that autistic children have imitating others.

For more than forty years, studies have been conducted in which

experimenters have asked children to imitate various behaviors and hand gestures

.

Children diagnosed with autism consistently perform worse

than typically developing children in these studies.

Once the mirror system was clearly linked with imitation

, the autism-related deficits in imitation led to a handful of neuroim-aging studies that resulted in the

broken mirror hypothesis

—that impairments in the mirror system may be the primary cause of autism.

Other books

Different Drummers by Jean Houghton-Beatty

Ash by Julieanne Lynch

The Other Child by Charlotte Link

Megan's Way by Melissa Foster

Jumping Puddles by Rachael Brownell

The Last Days of Lorien by Pittacus Lore

Accidentally in Love With a God (2012) by Pamfiloff, Mimi Jean

Operation Caribe by Mack Maloney

The Goose Girl and Other Stories by Eric Linklater

SirenSong by Roberta Gellis