Sisters in the Wilderness (48 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Maime, or Mary Agnes as she had been christened, was a particular favourite of Catharine's because she herself was now an author. In 1880, she had published a lively account of a trip she took by rail, steamer and road to Manitoba, where she spent some months as governess to the children of a

CPR

engineer. Maime was no fool: she had capitalized on her famous grandmother, Susanna Moodie, by calling her book

A Trip to Manitoba, or Roughing it on the Line

, and in an attempt to snare a valuable patron she had dedicated it to Lady Dufferin. Maime chatted away to her great-aunt as the train chuffed north. “You will I am sure like your great niece Miss Fitzgibbon,” Catharine wrote to Sarah Gwyllim, who had invited Maime to spend some time in England with her, “She is clever, practical and very agreeableânot pretty, but nice and lady-like and possesses much general knowledge and taste and the talent for writing which still belongs as a source of heirloom to the Strickland race.”

When the train drew into Ottawa's fussy little station, cab drivers looking for fares and boys eager to earn a few cents carrying baggage swarmed onto the platform. “I should have been perfectly bewildered by the jostling crowd of men and horses and boys pulling at one's sleeve,” Catharine recorded. But capable Maime elbowed a path through the throng, helped Catharine into a cab, bundled her up against the piercing east wind that cut through the town and told the surly Irish cab driver to take them to New Edinburgh, a small village about a mile east of the

Parliament Buildings. The cab bumped along the unploughed road and over the two rickety wooden bridges that spanned the frozen Rideau River. Soon Catharine was settled in front of a warm fire at 52 Alexander Street, the Chamberlins' pleasant brick house, barely two hundred yards from the Governor-General's gates at Rideau Hall.

Within a few days of Catharine's arrival, she was swept up into the social life of the capital by “the good kind [Colonel] and my dear Agnes C.” Agnes introduced her aunt to a social ritual that had not reached Lakefield: weekly “At Homes,” at which ladies received friends and acquaintances. “On Monday Mrs. C took me to call with her on Mrs. Macpherson,” Catharine wrote to Ellen Dunlop, “and it was

her day â¦

” Catharine, who had never had much time for social rituals, was both impressed and uncomfortable. “I saw several strangers â¦but they were all

rather

grand.” Next, Agnes hired a cab to take her aunt through Rideau Hall's wrought-iron gates and up to the viceregal front door so Catharine could write her name in the visitors' book. This would alert the Marquess of Lansdowne, recently arrived to serve as the Dominion's fifth Governor-General, to the presence in town of a distinguished visitor. “Oh Ellen! How I enjoyed the drive through the beautiful grounds and the dear snow laden evergreens of the woodsâit was a treat and took me back to old times but the deep, deep snow!⦠and the

coldâ

last night was 26Ë below Zero.”

The greatest excitement came in February, when an engraved and crested invitation arrived for Catharine from Rideau Hall. His Excellency the Governor-General, and his wife Lady Lansdowne, requested the pleasure of the company of Mrs. Traill at a winter soirée. On the evening of Saturday, February 23, Catharine, the Chamberlins and Maime Fitzgibbon swaddled themselves in buffalo robes for the short drive through the icy evening air under a star-studded sky. Catharine was in ecstasy: “The drive through the avenue among the snow laden trees was delightful â¦a splendid young moon just above the dark pine woods gave light enough to make every old leafless oak and silvery birch stand out from the darker evergreens in bold relief.” As the party

neared the Hall, they saw “a great vapoury cloud of smoke rising into the still air and spreading in fold after fold upwards above the trees, the lower part gilded till it appeared like a golden veil over the great solid banks of snow.” The next turn in the driveway revealed the flames of a giant bonfire leaping skyward and illuminating the toboggan slide. The toboggans “flashed past on their downward descent with a speed that almost took my breath to see their lightning-like swiftness as they flew past us,” Catharine wrote to Sarah Gwyllim.

Lady Lansdowne made the old lady feel very welcome. She took her arm and escorted her along a path, illuminated by Chinese paper lanterns hung from tree branches, to see the skating rink. The belles of Ottawa, cheeks flushed and eyes sparkling in the cold air, spun around as a brave little band played Viennese waltzes: “It was a pretty lively sight, the girls skating on this wood-encircled sheet of ice lighted up by torches on a little islet in the far end of the rink.” By now, Catharine was feeling chilled, so she and Lady Lansdowne went into what the latter called the “log cabin” to warm up by the stove. Catharine chuckled as she compared this Petit Trianon fantasy of life in the woods with her own memory of the real thing. “It was not a real log cabin, for it was ⦠handsomely panelled with varnished wood inside ⦠not rough and chinked and plastered as log houses used to be. This would have been a palace for a settler in the old settlement days of the Backwoods. We should have been thought too luxurious altogether and the house out of keeping with the rude furniture, diet and dress of that time.”

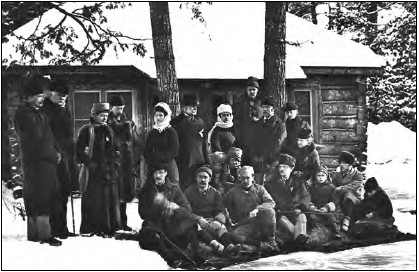

The 1884 skating party at Rideau Hall, organized by the Governor-General. Catharine found the log cabin “a palace â¦far too handsomely panelled.”

Up until this moment, Catharine had been enjoying herself. But she suddenly realized that people were staring and pointing at her. She heard people whisper, “That's her, that's Mrs. Traill.” Several of the voices spoke in the kind of aristocratic English accents that she thought she had left far behind her when she waved goodbye to England. A tidal wave of self-consciousness rushed through her. She felt out of her element, just as, years ago, she had felt unsettled within the unfriendly class system of Britain. Had her sister Susanna been the literary lion at this gathering, she would have watched with cool amusement the Henry James world of cigar smoke, rustling silk skirts and social nuance, as she had once enjoyed them in Thomas Pringle's house in Hampstead. Susanna would have risen to the occasion and revelled in being the centre of attention. But Susanna at that time was close to death in Toronto, and Catharine was acutely uncomfortable. Perhaps her nonchalance about her own appearance caught up with her in this plummy crowd; her coiffure might have suddenly felt dishevelled and her black silk gown (another Agnes hand-me-down) shabby. “Short people stood on tiptoe, and others peered over shoulders and pushed those before them aside peering at poor me as if I had been the shewpiece of the play,” she confessed to Ellen Dunlop a couple of days later. “The poor old lioness squeezed herself into a corner (I believe some people expected her to roar or wag her tail) not being accustomed to be gazed at in that wayâit was a little oppressive.”

Kind Lady Lansdowne rescued her guest and took her into Rideau Hall for refreshments. Catharine admired the platefuls of cakes and fruit, but contented herself with a cup of hot coffee. She was not

impressed by the manners of her fellow guests: “all seemed bent on making the

most

of the liberal hospitality of His Excellency.” But she herself made quite an impression on others. When Agnes Chamberlin told her friend Mrs. John Thorburn, wife of the librarian of the Canadian Geological Survey, that her elderly aunt was present, Maria Thorburn made a beeline for Catharine and introduced herself. “I do love nice old ladies,” Maria wrote in her journal. “And she is so interesting, over eighty ⦠I wonder if it is her love of nature that has kept her young and cheerful. Mrs. Traill has that pretty pink complexion that you see sometimes in old English ladies, a nice forehead and soft white hair.”

Catharine enjoyed her glimpse of viceregal life, but she had a particular motive for attending the Governor-General's party. She knew that James Fletcher, a botanist and entomologist who was then sub-librarian in the Parliamentary Library, was likely to be present, and she wanted to ask his advice about her plant manuscript. Towards the end of the evening, wrote Maria Thorburn, “Mr. Fletcher made his appearance. I vacated my seat to him and left him and the old lady to consult on the matter.”

Catharine had got to know James Fletcher in the early 1880s, when she had tentatively sent him her manuscript for comment. Fletcher, who was born in Kent, England, was still a young man, but he became an instant ally to Catharine because he was a natural historian of the old school. “I am charmed with your style and find it so attractive after the irreverent materialistic philosophy, falsely so-called, of too many of our contemporary naturalists,” he had replied. “It is very charming for me to see such love for our beneficent creation, and reverence for His perfect works.” He read her manuscript carefully, marking with a red tick those flowers that he thought she had identified incorrectly, or for which she had given the wrong geographic locale. But he was a tactful editor. He suggested he send her specimens of the plants he had queried, so she could check. And he assured her that he had “seldom enjoyed any âcommuning with nature' more than I have the perusal of

your thoroughly and patently original notes on our loveliest treasures, the flowers of the field.”

Catharine's Ottawa visit in 1884 allowed her to see other prominent scientific men in the capital. An extraordinary collection of self-educated and gifted engineers, geologists and biologists had gravitated to Ottawa after Confederation. These were men eager to participate in the great enterprise of discovering, mapping and developing the vast territories at Ottawa's doorstep. Many were associated with the Geological Survey of Canada, which had moved from Montreal to Ottawa in 1881; most were charter members of Canada's Royal Society, founded in 1882. Armed with specimen boxes and notebooks, they accompanied each other into the Gatineau Hills on the congenial field trips organized by the Ottawa Field Naturalists' Club (of which James Fletcher was secretary-treasurer). In 1884, and during a handful of visits Catharine subsequently made to Ottawa, these distinguished scientists went out of their way to pay homage to the old lady who had written

The Wild Flowers of Canada.

They recognized the value of Catharine's own painstaking efforts to record and celebrate Canada's native plants and Indian folklore.

The most significant of Ottawa's scientists to call at 52 Alexander Street was Sandford Fleming. Fleming, the surveyor and engineering genius behind the Pacific Railway, bubbled over with ideas to improve mail service, science education and communications. At the time of Catharine's visit, he was going full bore on the campaign for which he is best remembered: the need for global uniformity in time-keeping. (Before the nineteenth century drew to its close, the whole world would adopt his idea of dividing the world into one-hour time zones, with a mean time based on the prime meridian through Greenwich, London). He was also a generous teddy-bear of a man: instead of trying to remember the individual birthdays of his many grandchildren and their friends, he sent them all presents on his own birthday.

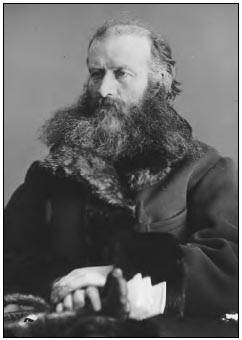

Fleming had met Mrs. Traill years ago in Peterborough, where he had arrived as an eighteen-year-old Scottish immigrant in 1845. When he heard she was in town, he immediately came calling. He cut a wonderful figure, with his huge bushy beard and powerful gait, as he strode through record-breaking snowdrifts from his mansion in Sandy Hill to the Chamberlins' house. Catharine was thrilled by his visit. “He was so kind and cordial it was pleasant to meet with the old dear and he said he would come again soon.”

A brilliant engineer, Catharine's friend Sandford Fleming (1827â1915) was the inventor of Standard Time and a man of irrepressible charm and boundless energy.

Catharine, indefatigable as ever, packed in plenty of sightseeing in the capital. She saw the fish hatchery organized by Samuel Wilmot, the Dominion's superintendant of fish culture, where trout, salmon, whitefish, herring, bass and pike were being bred to stock lakes and rivers. She admired the Dominion collection of stuffed animals and birds, and the collection of Indian canoes and artifacts, in the newly built Victoria Hall. Leaning heavily on Agnes Chamberlin's arm, she walked through the marble corridors of the Parliament Buildings and into the ornately carved elegance of the Parliamentary Library. She was almost overwhelmed when the Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, appeared “and greeted me very cordially.” These glimpses of scientific inquiry and national purpose were of much greater interest to her than Viennese waltzes.