Shorelines (37 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

On our way out the next morning, the

bakkie

fell deep into the soft sand once more. Everyone, including Grandma Molly, pitched in to help us out, bringing sticks and branches to put under the back wheels for traction. Even their Jack Russell puppy called Harry came running up with a couple of twigs in his mouth.

After the farewells, there was one more small mission left for us: to get to the Mozambican border and put an official cap on the trip. We drove the few last kilometres through grasslands and mealie fields and scattered kraals to the north-eastern edge of South Africa.

As we turned to go back, finger grasses bobbing in the wind at the side of the road waved us goodbye …

Aftermath

In the late winter of 2006, as we were putting

Shorelines

to bed, trouble was brewing off the West Coast of South Africa.

It had started five years before. Like the West Coast rock lobster, the sardines, and to some extent hake stocks, had slowly been taking leave of the most nutrient-rich, productive fishing grounds in the world, rounding the corner of Cape Point and spreading out eastwards.

When it happened in 2001, it astounded scientists and infuriated fishermen. Scientists had set high fishing quotas for sardines (also known as pilchards) and anchovies because there seemed to be a simultaneous boom in their populations – a highly unusual event.

But the sardines mostly eluded the pelagic fishermen, the shoals shifting almost to Port Elizabeth, making it uneconomical to follow them.

At the time, scientists said it was an anomaly, and fishermen hoped for better luck the following year. But the anomaly persisted, and grew even worse. The big fish shoals didn’t come back to the West Coast.

“Now there is not a pilchard left between Lambert’s Bay and Cape Point,” lamented René Zamudio, the retired pelagic fisherman we met at Laaiplek.

René still had his finger on the pulse of the industry. The steel trawler

Aranos

he used to skipper until 1994 was moored upriver from his house, and he continued to run the

Weskus Pelagiese Vissers Pensioenfonds

(the West Coast Pelagic Fishermen’s Retirement Fund), which has 700 active members.

“It’s a small community, and fishermen talk. The West Coast is in real trouble. Only the other day, I had dozens of fishermen outside my office, begging for help from the pension fund. Their cars are being repossessed. A few of them are at risk of losing their houses. They don’t know what to do. Some of the new entrants into the fishing industry, part of the transformation, are in so much financial trouble they can’t even pay their pension fund premiums.

“It’s not too bad for the big steel trawlers like the

Aranos

. The skipper tells me he is taking it around to Stilbaai, and they’re finding fish there. But the guys in the wooden boats, they can’t get there. They’re the ones in trouble.

“And you know what scares me? After August, the fish become fewer because they head down to the Agulhas Banks to spawn. I think the big problem is overfishing.”

Mossel Bay was now the unplanned epicentre of the pelagic fishing industry, with 27 purse seine vessels and four big steel trawlers operating out of the industrial town’s harbour. But all the canneries and packing plants were still spread out on the West Coast, from St Helena Bay to Saldanha, over 600 km away.

Horst Kleinschmidt, former head of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism’s (DEAT) Marine & Coastal Management branch, now managing director of Feike (Pty) Ltd – a fisheries and aquaculture advisory firm – said he recently calculated that the fishing industry spent R80 million last year alone, trucking the fish from Mossel Bay to Saldanha. The fishing companies have no idea whether they should be setting up their canneries at Mossel Bay or not, and no one can advise them. Will the sardines stay on the south coast?

And is overfishing really the problem? South Africa’s fish stocks have long been lauded as one of the most responsibly managed in the world. Our hake fishery was awarded the Marine Stewardship Council standard for sustainable fisheries two years ago, and generates R2 billion in foreign revenue a year from it.

But this white gold is in trouble too. It has also moved somewhat eastwards. More worryingly, Kleinschmidt says the size of the hake fished in South Africa’s waters has declined dramatically over the past few years, something that crops up in all overexploited fisheries. This creates a problem for the packing factories, which are not tooled up for such small fish. Some trawlers are tossing 30%, “or maybe even more”, overboard before they get to shore, says Kleinschmidt.

“It’s turning a crisis into a near calamity.”

There are also preliminary studies showing the sardine biomass may have halved from a peak of 2.5 million tons in 2003.

The problem seems to run deeper than overfishing. Kleinschmidt and fisheries scientists are now starting to believe the other smoking gun is climate change.

For decades now, biologists have been tracking the eastward movement of hundreds of species in South Africa, everything from plants to beetles to mammals. Atmospherics scientist at the University of Cape Town, Dr Bruce Hewitson, confirms that average global temperatures have risen by 0.63º C, and that they will continue to rise. No one knows where they will stabilise – the most conservative figure is a worrying 2º C higher (if nations cut down dramatically on greenhouse gas emissions) up to a catastrophic four to six degrees higher later this century (if they don’t), or even higher still. The entire country will become hotter, says Hewitson, especially in the interior, and drier on the west side of the country with higher rainfall in the east.

Species are voting with their feet, wings or roots – for a better chance in moister areas. But it’s only in the past five years that the fish have joined them, catching everyone by surprise.

The scientists focusing on the Benguela current that links Angola, Namibia and South Africa say there is “an increased frequency of warm events” in the northern Benguela.

They call them “Benguela Niños”. Fisheries writer Claire Attwood described them in an

Africa Geographic

article as “sustained events [with] large swathes of warm, highly saline water moving into northern and central Namibia from Angola.”

Dr Carl van der Lingen, pelagic ecologist at DEAT, is not entirely convinced that climate change is responsible for shifts in fish distributions, although he concedes that other species simultaneously moving eastwards could hint at it.

There may be other reasons for distribution shifts, he said. If the South African sardine population is divided into sub-stocks, each of which has a ‘preferred’ habitat from other sub-stocks, overfishing of the West Coast sardine population might be a factor. Or there could be some kind of climate variability (as opposed to change), which means the sardines may move back to the West Coast in the future.

Scientists have not picked up major environmental signals, such as an increase in sea temperature. And in any case, sardines are hardy fish that can withstand a wide temperature variation, Van der Lingen points out. They’ve been observed spawning in water with temperature ranges between 15º C and a balmy 22º C.

“We haven’t found a long-term environmental reason for the sardine shift eastward and I doubt it’s a simple one. Everything is so interconnected.”

What happens when sardines and other fish vanish from a region as rich in nutrients as the West Coast? For that, it’s necessary to look north.

Namibia’s pelagic industry crashed in the early 1970s after reaching breathtaking catches of 1.4 million tons at the boomtime peak in 1968.

By the early 1980s, Walvis Bay had hundreds of empty houses – it nearly became a ghost town as a result of the pilchard-business collapse. Thousands of dead Cape fur seals washed up on the beaches. The sardines never really recovered. Today, Namibia keeps its canneries ticking over with an annual catch of less than 25 000 tons, even though scientists advise zero take. The stock is erratic. In 2003, the research ship

Welwitschia

did not find a single pilchard in Namibian waters.

Yet the marvellous West Coast upwelling just rolled on, the wind-driven currents bringing up nutrients from the depths – the very reason these waters were once so rich in fish. Now mostly uneaten, the plankton do not enter the food chain and slowly sink back to the deep, their decomposition sucking oxygen at the bottom of the sea to create dead zones and sulphur eruptions.

Benguela ecosystem scientists are starting to talk about a serious degradation of the system.

DEAT ecosystems modeller Dr Lynne Shannon confirmed that jellyfish, millions of tons of them, have partially taken the place sardines and anchovies have left vacant in Namibia. They’re voracious eaters of floating plankton – and, more worryingly, of sardine eggs – so Namibia may never see the return of its pelagic wealth, apart from pelagic gobies, survivors because they are bottom and midwater feeders.

Could the same happen in South Africa? No one knows for sure, because no one can tell whether the change is permanent.

The seabirds, meanwhile, have followed the fish eastwards.

Namibia’s offshore islands used to be covered with seabirds. Now many of them are completely barren, and the same may happen on the West Coast.

Keith Harrison, chairman of the West Coast Bird Club, says that 2006 is the first year a colony of 800 hardy kelp gulls he sees regularly on the lower Berg River wetlands has produced only a handful of chicks.

“They can survive on trash and termites themselves, but they need to feed fish to their young, and they just aren’t finding fish. The Caspian terns that breed here, the biggest population on the West Coast, left after a few days.”

The numbers of seabirds might have plummeted on the West Coast, but are up on the southern and eastern coasts.

Hartlaub’s gull is now breeding near Port Elizabeth, 550 km further east than it did 10 years ago. Wilfred Chivell of Dyer Island Cruises in Gans Bay has noted a dramatic increase in swift terns nesting on Dyer Island, from 1 250 pairs to 6 700 pairs in one year. More albatross are being seen, especially the shy albatross, but also the Indian yellow-nosed and the grey-headed, perhaps because of the wealth of fish crowding the Agulhas Bank.

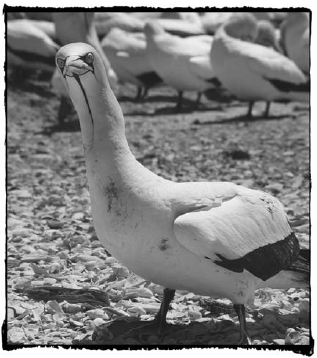

Cape gannets have mostly followed the shoals. About 11 000 pairs of gannets were flushed off their nests by marauding seals eating adults and nestlings on Lambert’s Bay’s Bird Island in November 2005. But gannets, somewhat tragically in view of the vanishing fish stocks, are very loyal to their nesting sites and mates. By July 2006 a few hundred had come back in preparation for the September breeding season, and were being guarded by a marksman ordered to shoot any seal that approached the gannet nests.

There are also reports that 87% of gannets fledged from Malgas Island were eaten by seals on their first flight to sea.

By contrast, Bird Island off Port Elizabeth is now home to a soaring gannet population – 170 000 at last count.

Why are seals attacking birds on the West Coast? Are they desperate because there are not enough fish to eat?

Dr Tony Williams, seabird biologist for Cape Nature, based at the Avian Demography Unit at UCT, has studied the back story of seals. In pre-European history, they were simply never found on the mainland, because any seal that swam ashore was clubbed by

Strandlopers

who pursued them for fat to supplement their otherwise lean shellfish diet.

It was only in the 1930s that they began to set up colonies on the mainland, on the undisturbed beaches within West Coast and Namibian diamond concessions. The population limits of islands fell away. Cape fur seals now number a million in Namibia and two million in South Africa. (Namibia recently announced it planned to cull 91 000, saying they posed a serious threat to their fishing industry.)

Dominant males create harems of compliant females. But the young males are always on the lookout for “something on the side”, explained Dr Williams, and they want to stay close to the colony, unwilling to forage far offshore. If there is little or no fish in the water, they’ve learnt to supplement their diet with seabirds, attacking them on their nests. Some male seals now specialise in eating gannets on their nests, others in eating penguins in the sea – a vicious process called degloving, when the penguin is shaken so hard that its skin comes loose from flesh and bones. Seal attacks are one of the main reasons for a serious decline in penguin numbers.

What is the solution? The climate change issue will be with us for decades, probably centuries. South Africa produces 1.4% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and has taken some preliminary steps to cut this down, but the world’s coal power stations are steaming on.

Kleinschmidt proposes that the West Coast fishing industries look to the underutilised horse mackerel instead, and the cultivation of perlemoen and oysters. And there are other things to do with anchovies than make fishmeal, he says. “It is astounding that we buy filleted anchovy from Italy and Portugal at R50 a tiny bottle. That could create a few more jobs.